Last week in this column we opened a window onto the slow movement and the architecture that has been enfolded under its banner.

That article closed with the suggestion that the core tenets of slow architecture were something that truly great architects had always encompassed within their practice.

I’d like us to explore that further by considering two of those “great” architects: the first played on a world stage, while the second chose to practise his craft in this region.

Frank Lloyd Wright believed common buildings were boxes that placed limits on what the occupants could do and see, a reinforcement of social conventions that curtailed both dreams and aspirations.

He suggested self-actualization begins in designed spaces that are not a series of boxes packaged in a box, but rather holistically integrated (both interior and exterior) to produce experiential opportunities for creative and contemplative thought.

That he, during his career, was committed to “breaking the box” can be seen through his address to the Junior Chapter of American Institute of Architects (New York City) in 1952 in which he stated: “I think I first consciously began to try to beat the box in the Larking Building – 1904… Unity Temple is where I thought I had it, this idea that the reality of a building no longer consisted in the walls and roof.”

From his “In the Cause of Architecture” essays (VIII – 1928) we can see how important a place this “breaking the box” consideration held in his design ethos when he writes: “The walls themselves cease to exist as either weight or thickness. Windows become in this fabrication a matter of a unit in the screen fabric, opening singly or in groups at the will of the occupant.”

In other words, a building design of spaces should provide for unbroken support, in and of the moment, of the occupant’s thought and/or creative processes. Walls, ceilings and floors should not limit, but rather free, self-actualization.

Further, Wright was a proponent of architecture that learned from and followed nature. He wanted to build with the land, not on it.

So, to be very clear, he was not a proponent of copying the forms of nature or subsuming his designs into the landscape. His position was that you take inspiration from the natural site and govern your design accordingly.

In Wright’s “In Cause of Architecture” essays in 1908, he wrote: “A building should appear to grow easily from its site and be shaped to harmonize with its surroundings if nature is manifest there and, if not, try to make it as quiet, substantial and organic as ‘she’ would have been were the opportunity ‘hers.’ ”

In these two (selected from others) criteria, Wright exemplified, or perhaps first articulated on a global stage, the core parameters of the 21st century slow architecture school.

Throughout his career he sought to create spaces that would free the mind or, as he put it in “Modern Architecture” (The Kahn Lectures, 1931), “Architecture must now unfold on inner content – express ‘life’ from the ‘within.’ ”

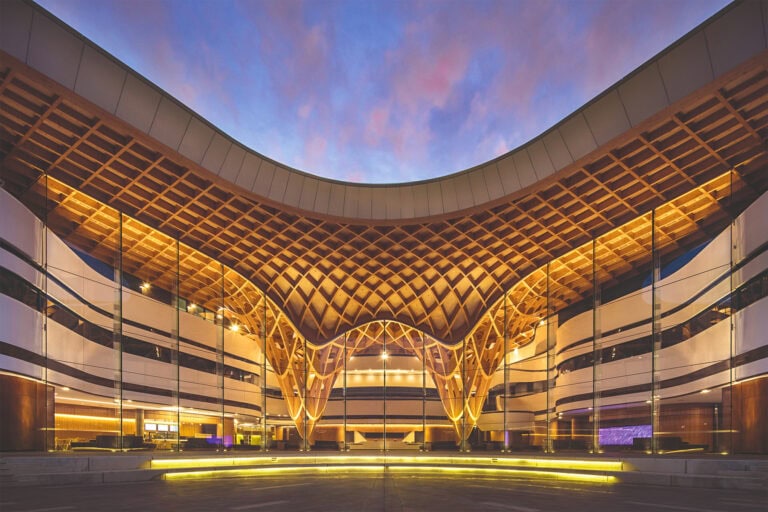

Now, let us move on to another architect, a western boy who settled in Niagara and never left.

That Don Chapman believed in the same central tenets to which slow architecture ascribes can be best illustrated by his personal home on Niagara River Parkway. Here, unconstrained by any client limitations, he was allowed to fully express a design founded in those beliefs.

From the river, the house sits slightly below the brow of the river bank while from the street, it settles into the landscape, echoing the topography to extend its natural elements into the built form.

In my mind’s eye, I can see the architect on the vacant lot, carefully plotting perspectives and lines of sight before commencing his work on the design, for this would be a house of seamless transitions from the interior to exterior, with every space devoted to giving people that mind-freeing experience.

Constructed of locally sourced, largely natural materials, the oak timber framing softens and contrasts against the white structural brick walls, while earthy tones of the polished brick floors ground the spaces.

Ceiling-to-floor glass windowed colonnades connect four distinct pavilions organized around accessible exterior courtyards, with each pavilion designed to augment a measured, thoughtful lifestyle. And every space presents its own incredible views onto the river and into the Carolinian forest of the riverbank.

The completed design creates a gestalt that results in a sense of Zen that has rarely been produced by North American architecture. Moreover, in the five decades since it was built in 1970, the building has aged beautifully in the context of its setting.

In short, it is a tour de force, a masterwork of organic design that exemplified the principles of slow architecture 40 years before that movement came to be.

That in no way diminishes slow architecture but, rather, lends it the weight of a tradition explored by great architects of the past.

Brian Marshall is a NOTL realtor, author and expert consultant on architectural design, restoration and heritage.