What can be done with cities that have grown based on automobile dependency?

Sprawling across many square miles, we have created urban environments that have little (or nothing) to do with community. Your friends are not often your neighbours but rather people at the other end of a car trip between your home and theirs.

Gone are the neighbourhood mom-and-pop stores and businesses subsumed into centralized retail centres serviced by roads and highways.

Gone too are local schools, rinks and parks; children are bused to school or driven by their parents while rinks and parks are not for simple play but rather complexes devoted to organized activities that people get to by car.

Is it really any surprise that today, more often than not, the word social is only heard in the context of social media?

As slaves to our automobile culture we have created vast sterile seas of suburbia in which each house is an isolated island and public transit, whether by rails or wheels, is woefully inadequate because we have cars, don’t you know.

Today our cities face a dilemma in housing. The cost of housing, driven by practical limitations of distance and an increasing shortage of developable (in the traditional format) land, has risen beyond the means of many first-time home buyers (and others) while at the same time rents have wildly escalated to consume a significant portion of average take-home pay.

But cities cannot be viable without this demographic nor without the contribution of new immigrants.

In the last 60 years we attempted to answer this growing problem with densification in the form of highrise condominium towers, essentially a vertical expression of sterile suburbia.

And while this worked for a while to provide dwellings for young singles or couples, it is extraordinarily challenging to raise a family in a 450- to 700-square-foot cubicle in the sky, particularly when the stressors inherent in high-density environments are multiplied by the absence of any form of integrative local community.

So, if going out or up doesn’t work, how can cities find a solution to this growing problem?

To partially answer that question it behooves us to look at city neighbourhoods built before the domination of the automobile (many of which are still viable communities today).

Many old European cities can loosely be described as “cellular” in nature. Each “cell” has a radius often no greater than a 10- to 15-minute walk from its core (and sometimes much smaller).

At that core is a central square (piazza, plein, plazuela, praca, etc.), which often has both stores and open-air vendors.

Many of the buildings (often 2.5 to five storeys tall) along the streets and laneways leading out of the core are mixed-use, for example with a shop, bistro, cafe below or at grade, above which are dwellings ranging from flats to multi-storey family homes.

Each of these cells is a walkable distinct neighbourhood which today is commonly serviced by public transit along the shared neighbourhood periphery.

These neighbourhoods work because each has a relatively small population encompassing a range of income levels, are walkable, mixed-use buildings promote social interaction, the central square forms a venue for community socialization and many of the residents’ daily needs can be met inside the neighbourhood.

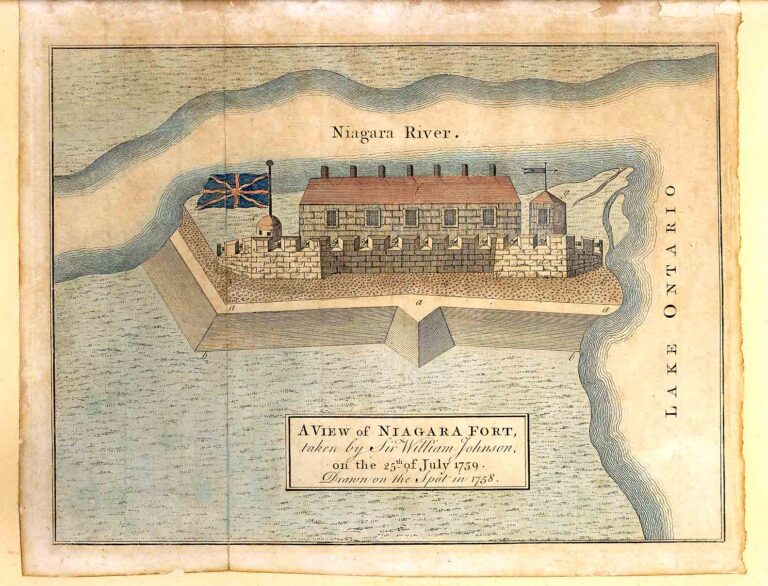

As our cities rethink their viability for the next 100 years, this cellular neighbourhood concept drawn from our past should be front and centre in their planning. And indeed, it should be enfolded in Niagara-on-the-Lake’s future vision as well – because the creep of failed suburbia is happening here.