Dr. William Brown

Special to The Lake Report

In 1979, Frans De Waal, then a young primatologist, wrote what turned out to be a bestseller, “Chimpanzee Politics,” which caught the attention and fancy of a wide swath of American readers and politicos.

The book was based on De Waal’s observations of a colony of chimpanzees at the Bergers Zoo in Arnhem, Netherlands, where several generations of chimpanzees live on a two-acre island surrounded by a water-filled moat that allows observers plentiful opportunities to observe chimpanzee behaviour and relationships over many years.

Newt Gingrich, the then powerful Republican speaker of the house and many of his congressional colleagues, got a kick out of the close parallels between the political shenanigans of members of the mostly male congress and the behaviour of the male chimpanzees.

In his book, Frans De Waal suggested that entire passages from Machiavelli’s classic book, “The Prince,” first published in 1532, (which chronicled the sometimes-devious alliances and schemes ambitious princes used to gain and hang on to power), were directly applicable to the behaviour male chimpanzees display as they wheel and deal to maintain and extend their influence and power within the colony.

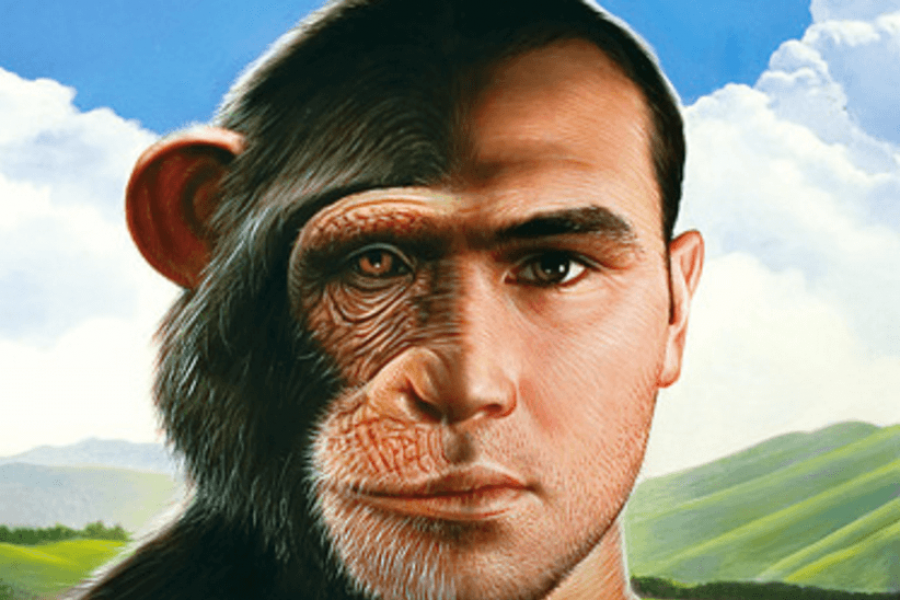

Such a similarity in behaviour, between the two primate species, suggests a common evolutionary root.

At the genomic level, early DNA studies suggested that chimpanzees and humans, share all but 2 per cent of their DNA with one another. Maybe so, but those DNA studies obviously don’t tell the whole story, given that the brains of chimpanzees are roughly one-third the size of the human brain.

Most of the human expansion was in the neocortex, especially areas related to our far more developed symbolic speech characteristic, and the sheer range and number of human achievements in the arts and science that far surpass anything any ape has done, however clever they might be.

However, similarities between the two species may be much closer at the level of social intelligence and the role emotions play in their behaviour. Social intelligence involves the ability to navigate the social landscape, which begins with a well-developed sense of self-awareness and extends to the ability to read the emotions and perhaps intentions of others, both with respect to oneself and among others in a group.

Chimpanzees can be quite clever and cunning in furthering their ambitions within the hierarchy of males and the larger troop, by forming alliances of convenience to boost their status relative to competitors or hold on to power, including the power to control access to sex with females in oestrus. And like some humans, they remember grievances, sometimes for years, before settling old scores at times and places of their choice.

With males, it’s all about dominance, ambition and preferred access to mates. Alpha males can be very jealous and controlling in access to females, although most of the time, females get to say no, and rape is unusual. Females are more tuned to relationships, which tend to be much more stable and longer lasting than relationships between males, who tend to be more calculating and strategic in nature in fostering or breaking relationships.

De Waal points out that while high-status males are much more concerned with any breach of sexual access, females are more concerned about whether breaches involve a loss of a close (dare I say, loving) relationship with another chimp.

But the most impressive figure to emerge in troops of chimpanzees are the grandmothers, the “mamma” figures who, despite their greater age and physical fragility, are highly respected by both sexes and often the “go to person” for settling disputes.

In one example, a trio of males was chased up a tree for transgressions and kept there by others in the troop. It was “Mama,” the grandmother, who finally climbed the tree, kissed and hugged them and then led them down the tree to safety, with no challenges from any member of the troop. That’s power.

What struck Gingrich and other politicians 40 years ago, and since, was that power-seeking behaviour in humans, even if well-masked, closely parallels the hierarchical, power-seeking actions of male chimps, including seeking advantageous alliances with others.

All of this suggests such social behaviours have deep evolutionary roots – at least as far back as the last common ancestor for the apes and humans, and possibly much longer. And although our clothes and possessions differ from the “naked ape,” our naked behaviours, at their roots, are very similar. That’s unnerving!.

Dr. William Brown is a professor of neurology at McMaster University and co-founder of the Infohealth series held on the second Wednesday of each month at the Niagara-on-the-Lake Public Library.