Science, art and religion may be part of the human landscape but in the present day they tend to be separate despite common, deep evolutionary roots.

For most modern humans, visual art is identified with pictures hanging on walls in homes, galleries and museums, and illustrations in books or magazines. And these days music of all genres is readily accessible using apps on smartphones and computers or perhaps by attending concerts.

Science for most was something studied in high school after which there’s little further exposure except for occasional media-hyped stories of rovers on Mars, pictures of the early universe courtesy of the new James Webb telescope or perhaps the latest controversial fossil discoveries to shed new light on the human origins story.

For its part, religion, is usually learned and experienced in communities identified with synagogues, mosques, churches or other sacred places, each associated with their own take on culture, beliefs and the divine.

Although science, art and religion in the modern world tend to be separate, for many centuries in the Western world, art and religion were knit together in images, music and ritual.

But for more than 99 per cent of the time that behaviourally modern humans and Neanderthals walked the Earth, aspects of what we might identify as science, art and religion were seamlessly woven into their everyday lives.

Science in paleolithic times would have been reflected in the skills with which raw materials were selected (such as stone, wood, bone and ivory) and fashioned by modern humans and Neanderthals into tools for everyday living, hunting and the creation of sturdy, durable shelters.

Similar learning by observation and experience would have been essential for understanding day-to-day and seasonal weather changes, the behaviour of animals (including their seasonal migrations) and the selection and locations of edible plants and much else in the natural world on which they depended for survival.

In paleolithic times, the creation of art objects involved fashioning suitable materials to create figurines and musical instruments such as drums and flutes.

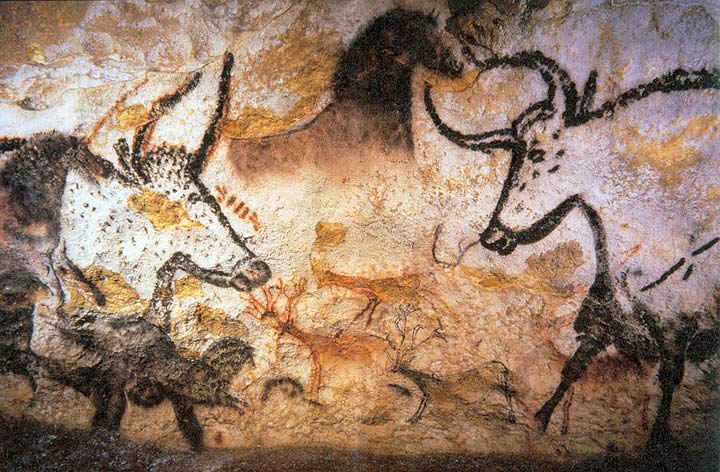

From marine shells and the shells of ostrich eggs, beads and other decorative jewelry were created, some of which became valuable, tradable goods. And pigments such as ochre were used to create images on cave walls and probably decorate human bodies. All required skill and a sense for beauty.

What about religion? Life in paleolithic times was mysterious and dangerous.

For this a brain capable of considerable inventiveness, imagination and symbolic thought and speech would have been essential for the development and evolution of creation myths to make sense of their lives.

We don’t know where or when the earliest symbolic languages emerged but it’s hard to believe that the creation of hybrid statues such as “lion-man,” with the head of a lion and body of a human, or the many fine examples of paleolithic art in Europe and Indonesia would have been possible without sophisticated, symbolic oral language to create stories and share them among clans.

With so much mystery in their lives, it’s likely that early humans imagined supernatural and spiritual relationships with heavenly bodies, fearsome predators such as saber-toothed lions, or cave bears, and perhaps endowed them with god-like powers and worshiped them in some fashion.

Like modern hunter-gatherer societies, those stories defined who they were as a people and reminded them of ancestral leaders, heroes and beliefs.

The earliest stories were likely recounted by the head of the band or revered elder and in later times, a male or female shaman.

However, once humans settled in larger communities what had been shaman-created and led stories became systematized, ritualized and most importantly, codified in written language. Priesthoods emerged as intermediaries between the gods or perhaps a god and humans.

Like the evolution of creation stories and mystical relationships with the spirit world and gods, so also art and science evolved. Those stories, especially those related to science, are what I hope to explore in a new series at the NOTL Pubic Library beginning in early February, titled, “Beginnings to Endings, and Around Again.”

The series focuses on the beginning of the universe, the lifecycles of stars, the creation of the elements, the creation and life of black holes, the chemistry of life and – finally – what the end of the universe might look like.