Penny-Lynn Cookson

Special to Niagara Now/The Lake Report

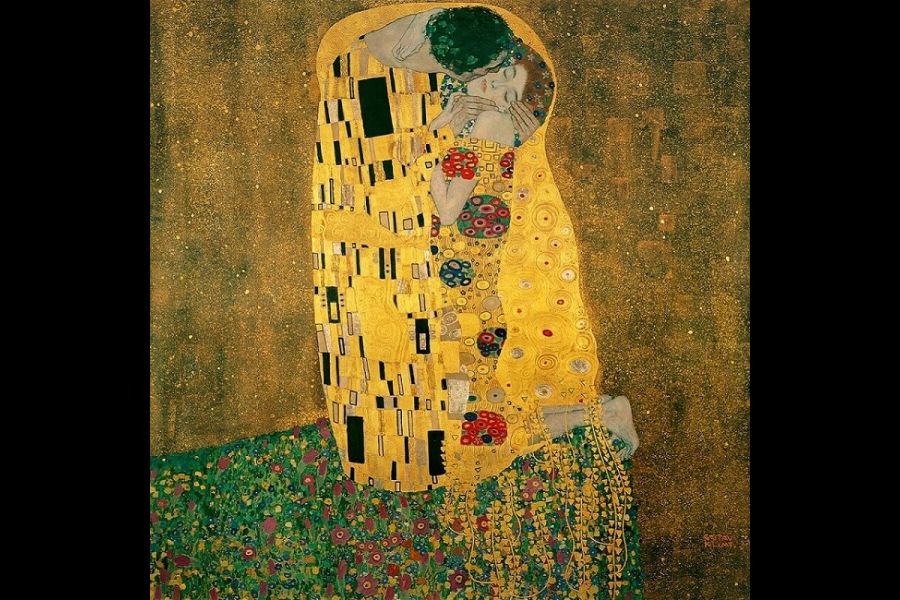

Is there a more rhapsodic image of intimate love than Gustav Klimt’s “The Kiss”?

As we move on from COVID elbow taps to tentative hugs to longed-for kisses, it may be a surprise that this image of tender and enduring passion caused considerable controversy in Vienna.

Klimt was, undoubtedly, smarting from the criticism and rejection of three commissioned works he had created for a ceiling of the University of Vienna. His painted female nudes, appearing as metaphors for philosophy, justice and medicine, were received with outrage as pornographic. They hastily were removed and years later destroyed by the Nazis.

In spite of this uproar, “The Kiss” was purchased before its completion in 1908 by the City of Vienna for 25,000 crowns, the equivalent of $250,000 U.S., an astronomical sum at the time. In 2003, Austria honoured Klimt and “The Kiss” with a commemorative 100 Euro gold coin. What led to this turn of events?

At the turn of the 20th century, Vienna was in a period of intense change and modernization. Social and religious traditions were being challenged, radical philosophies were rampant and the psychological research and writings of Sigmund Freud were making a startling impact.

Gustav Klimt, having studied at the School of Arts and Crafts, spurned its academic formalities in search of new elements of design and new themes of investigation, including desire, sexuality and psychology. He became a founding member of the Vienna Secessionists and a pioneer of Symbolism and Art Nouveau.

“The Kiss” was created at the peak of his “golden period,” when gold leaf was used to great shimmering effect in his most renowned paintings. Klimt was familiar with the use of gold as his father was a goldsmith and engraver.

Twice he travelled to Ravenna to study the Byzantine mosaics at the Basilica of San Vitale and was inspired by their two dimensionality and the glittering effect of light on the golden images. In “The Kiss” a couple appear to be completely wrapped in an intimate embrace of passion.

The man bends to kiss the pale cheek of his beloved. He holds her face with hands strong but gentle. Her face is passive, eyes closed, but her delicate hands are surprisingly tentative. One hand clutches at his hand, the other appears weak and almost transparent behind his head. Her bare toes are bent, digging into the edge of the carpet of the grassy flowered meadow they kneel on, her feet exposed to the unknown space of the abyss behind.

Only a flowering tendril across her ankles seems to anchor her. The man wears the mythological laurel crown of Apollo. The woman’s red hair is surrounded by a halo of small mauve and purple flowers. The work is highly decorative, with juxtaposed textures and Art Nouveau patterns.

The man’s strong geometrical robe of black and white rectangles contrasts with the woman’s form-fitting dress of colourful organic circles and ovals. In spite of the closeness of their bodies, Klimt’s use of fine lines, vivid colours and contrasting patterns reveals a distinct separation, a duality not only conveyed by these patterns but in the tension inherent in the act of passion between two individuals in love.

Is it a mythological story of loss? Orpheus and Eurydice? Or Klimt’s unabashed exploration of human sensuality and emotion?

He was, after all, a man known for his many lovers and 14 children, who stated: “Whoever wants to know something about me should look attentively at my pictures and there seek to recognize what I am and what I want.” Your call.

Penny-Lynn Cookson is an art historian who taught at the University of Toronto for ten years. She was also head of extension services at the Art Gallery of Toronto. See her lectures on “Landscape and Memory’”on Zoom at the Pumphouse Arts Centre, Aug. 4 to 25. Registration is free.