Penny-Lynn Cookson

Special to Niagara Now/The Lake Report

In this time of lockdowns and isolation and bans on social gatherings in restaurants and pubs, sales of wine and spirits have increased with quiet, at home imbibing.

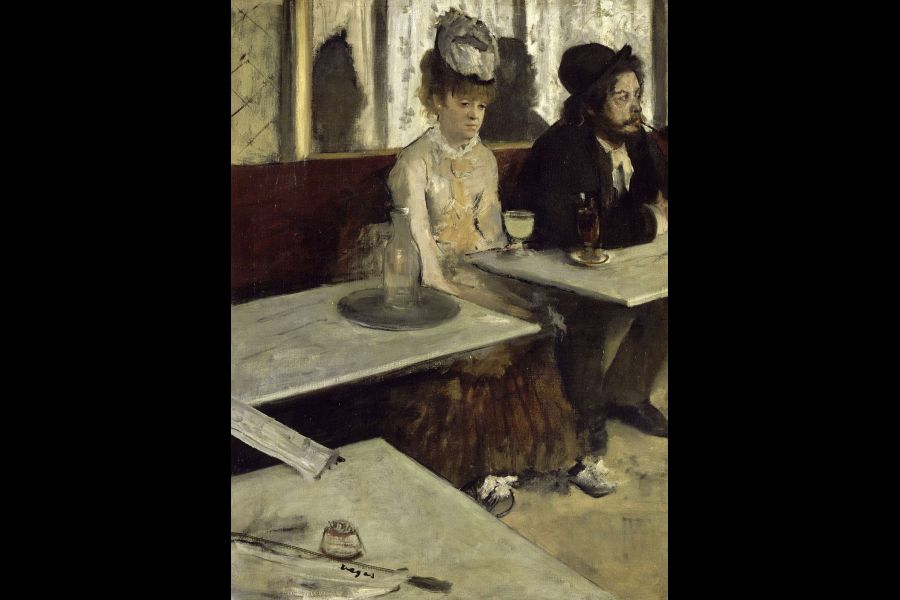

In “L’Absinthe” of Degas, the subject matter of this solitary detached couple drinking in a café became all too subjective in the harsh disapproval of critics who saw it as a shocking moral tale of the dangers of absinthe. This ultimately led to the banishment of its sale and contributed to the rise of the temperance movement. That certainly was not the intention of Degas when he painted it.

Degas, like many of his artist colleagues, lived in the bohemian Montmartre area of Paris, and frequented many of its cafés, including the Café de la Nouvelle-Athenes, the location for “L’Absinthe.”

Although schooled and successful in the academic tradition of history paintings and a participant in Impressionist exhibitions, Degas was a modernist interested in the lives of ordinary people, usually women working as laundresses or milliners or the young dancers of the ballet.

What he conveys here with his ever-inquisitive and investigative mind is a realistic scene combining memory and innovation. Two acquaintances were used as models, the actress Ellen Andrée and the engraver Marcellin Desboutins.

Rather than being in a boozy haze, they were undoubtedly exhibiting the fatigue of long hours holding their positions in his studio. Unexpectedly, the painting was highly detrimental to the careers of both as they were erroneously described as degenerates and Degas had to publicly defend them as not being alcoholics.

In “L’Absinthe,” the couple sit side by side but apart, non-communicative, lost in their own worlds. The woman gazes down into space, her glass of absinthe untouched, the carafe of water empty. A glass of cold coffee, sits in front of the man, who surveys something to his left, his pipe, arm, hand and toe cropped as they might be in a photograph.

Degas was a keen follower of the new art form, photography, and this composition with its rising right oblique angle is no longer the perspective of a single view. He is also fascinated by Japanese prints and his asymmetrical use of the three marble tables jutting into the foreground space and across the woman reflects this.

A rolled newspaper serves as a bridge between two tables and a matches container and a drawing sheet with the artist’s signature on it add further detail to a radical viewpoint.

Degas saw the world in a different way technically and morally. He aimed to show things as they actually were not as they might be. The result was striking.

Penny-Lynn Cookson is an art historian who taught at the University of Toronto for 10 years. She also was head of extension services at the Art Gallery of Ontario. See her lecture series “Art and Revolution, From Cave Art to the Future” Thursdays on Zoom until April 29 at RiverBrink Art Museum in Queenston.