Dr. William Brown

Special to The Lake Report

To hear proponents of evolution speak, evolution was (and is) all about natural selection by favouring certain traits, which might offer some advantage in a competitive world for survival created by the environment, including climate, food sources and safety from predators and disease.

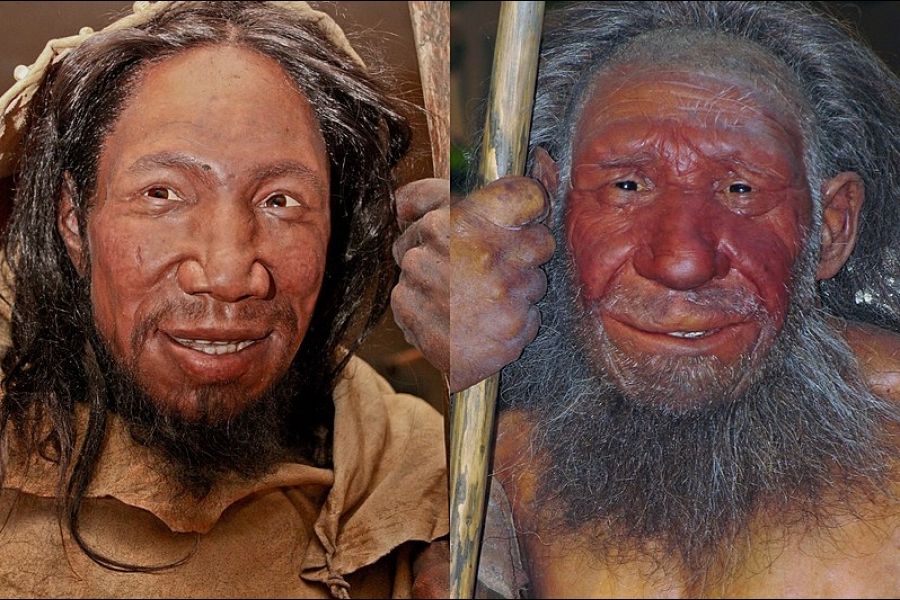

Of course, what defines fittest depends on the bias of those making the judgement. This was never more obvious than in the long debate about whether neanderthals had the cognitive wherewithal to compete with modern humans.

For much of the time since the prominent bony eyebrows and thick-boned skeleton were described, neanderthals were considered relative dimwits compared to modern humans, despite a brain cavity equal or larger than that of modern humans.

Indeed, the reason neanderthals became extinct was assumed to be that they couldn’t cognitively compete with modern humans. That was the story until the last two decades, when startling discoveries revealed that not only were neanderthals capable artists (based on many examples of their cave art), but that art was created a minimum of 20,000 and possibly as much as 90,000 years before modern humans lived in Western Europe – and that’s using highly accurate dating techniques.

So, neanderthals clearly had the imagination and symbolic thinking to create art and very likely possessed symbolic language as well – traits hitherto considered to be exclusive to modern humans. They also created jewelry from seashells long before similar jewelry was created in South Africa 70,000 years ago. This comparison of creativity in neanderthals and modern humans illustrates just how treacherous assumptions can be when they’re based on flimsy evidence.

However, there are plenty of examples of natural selection at work, such as the shaping of the size, shape and length of bird beaks to best fit changes in the configuration of flowers from which birds feed, and the shape, size and colours of fish belonging to the same root cichlid species, to match changing environmental niches for food and safety in Lake Victoria in Africa.

But there’s more to natural selection than physical and cognitive traits, which are the usual traits touted as targets for natural selection. What about beauty as a force for selection?

There are plenty of examples where beauty trumps other traits – none better than the case of bower birds and birds of paradise in southeast Asia and Australia, whose extraordinary colours, elaborate courtship behaviours and decorated nests were wonderfully celebrated by David Attenborough, as among the clearest testimony to the power of beauty as a selective force.

Looking good has its risks however – all that colourful plumage, elaborate stage-set, and dance routine draws attention from predators.

Which brings us to Valentine’s Day and human attraction and love. Just how important is physical beauty to human relationships, courting and mating?

To judge by the actors chosen for certain movie roles, magazines at checkout counters in variety and grocery stores, and the size of the beauty-aid industry, physical beauty surely counts for a lot, at least for first impressions.

But what constitutes beauty in humans varies all over the map. In paleolithic times (between 11,000 and 35,000 years ago), “Venus” statuettes were common, which showed big-breasted women with genitalia and body sizes to match. Yet in the world of fashion, preferred body shapes and facial features vary wildly from age to age and culture to culture.

Beyond physical traits, personality, behaviour and character are surely as important, or more so, than physical features, especially for long-term relationships. Many would rank day-in, day-out thoughtfulness, respect, and love, and yes, romantic attraction, as very important. These and other traits, to which readers might want to add their own picks, wear well over the long haul and often dictate whether relationships have staying power.

Valentine’s Day is as relevant for oldsters as teenagers, if not more so, because we’ve had more experience with the game of life and love, and found out a thing or two, sometimes the hard way, for what works and doesn’t work in relationships. We all know couples (and may indeed be one of those couples), who know what it means to be happily married for many decades, where the relationship grows from strength to strength, even if, as happens eventually, the body begins to fail.

Dr. William Brown is a professor of neurology at McMaster University and co-founder of the Infohealth series held on the second Wednesday of each month at the Niagara-on-the-Lake Public Library.