If there’s a butterfly anyone can identify, it’s the monarch.

That’s why the migratory monarch’s new designation as an endangered species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature is “really sad,” says a woman known as Niagara-on-the-Lake’s “Butterfly Queen.”

“This is why I’m doing all I can to educate others,” said Charlotte Letkemann, who has spent decades learning about butterflies.

The retired teacher’s passion for butterflies started in 1970 when she discovered two cecropia moths mating.

As a teacher at the time, she was always interested in learning new things, she said. She covered the moths with a net and the next morning, though the male had got out, the female laid eggs.

It’s now 52 years later and butterflies are a huge part of her everyday life.

She wants to educate others about butterflies and what they can do to help the species. She often goes to seniors residences and gives presentations to those who are interested.

Letkemann encourages residents to plant native milkweed in their gardens. Milkweed is where butterflies lay their eggs. The butterflies lay an egg on the bottom of each leaf.

The conservation union also suggests reducing pesticide use.

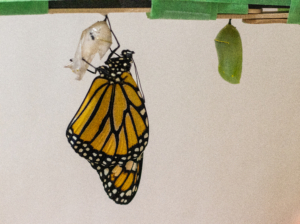

Letkemann enjoys watching the four stages of a monarch life from inside her home. Once they emerge as a butterfly from the chrysalis, she releases them outside a few hours later.

Credit: Somer Slobodian

A monarch butterfly that just emerged from the chrysalis at Charlotte Letkemann’s NOTL home.Migratory monarchs travel 4,000 to 5,000 kilometres from Canada to the mountains of Mexico each year to hibernate.

Six years ago the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada also listed monarchs as endangered.

This used to be the longest known migration of any insect. That was until the dragonfly beat it, said Dr. Gard Otis, a retired behavioural ecology and apiculture professor from the University of Guelph.

There are many non-migratory monarchs around the world that are not endangered, said Otis. It’s the two species seen in North America – the eastern monarch and the western monarch – that are in serious trouble.

“The monarch is not going to disappear from the planet, but the concern is that the migratory population that we know in North America could disappear, either largely disappear, or completely disappear,” he said.

Eastern migratory monarchs spend their winters in Mexico, then make the journey to the north in late February or early March.

Throughout their trip, they give birth many times, producing multiple generations. Only about 10 per cent of monarchs from Mexico make the full trip to Canada.

The rest that arrive here are the offspring born along the way in the southern states. By the end of each summer, the fourth-generation monarchs are ready to make the trip back to Mexico.

From 1996 to 2014, the eastern monarch population declined by 84 per cent, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

But, the western monarch is at even greater risk of extinction.

Western monarchs are a smaller population and overwinter in California. They make the journey west of the U.S. Rockies in spring and summer.

The conservation union’s website says between the 1980s and 2021, the population declined by 99.9 per cent, from 10 million to fewer than 2,000.

But this year following the New Year’s count, remarkably, 151,168 were tallied at 209 overwintering sites. This follows the Thanksgiving tally in 2021 of over 250,000 western monarchs.

However, due to extreme climate change, increased use of pesticides, habitat loss and invasive species the number of migrating monarchs continues to be a major concern.

The Oyamel Fir Forest is a popular spot in Mexico for monarchs to spend winters. Due to deforestation and thinning, the monarchs are becoming more exposed to dangerous conditions such as winter storms and cold temperatures.

In California, real estate development is one of the biggest threats to the western monarch.

There wouldn’t be any catastrophic effects to the ecosystem if we lost the migratory monarchs. But, we would lose great pollinators and a butterfly that is beloved by many.

“If people in Ontario know any kind of butterfly, they know the monarch,” said Otis.