Some field workers only have plastic tub to do laundry

Some NOTL farmers unknowingly might not be living up to federal contracts with their seasonal workers thanks to confusing rules over something most Canadians take for granted – doing the laundry.

Guidelines from federal and provincial governments differ regarding laundry facilities and, in turn, Niagara’s regional public health department is the agency that handles inspections. And it follows Ontario’s rules.

An investigation by The Lake Report into farmworkers’ laundry facilities was prompted after Niagara-on-the-Lake seasonal worker Ceto Reid was badly injured while riding his bike in St. Catharines.

He was returning from a laundromat, toting his laundry, when he was struck by a car on Oct. 6.

Migrant workers come to Niagara-on-the-Lake every year through the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program to help area farmers with the intensive work of planting, caring for and harvesting various fruits and vegetables.

Under the federal program’s contracts, farmers are required to provide accommodations and a series of amenities that go with them – including laundry.

Credit: Supplied

This is what it says about laundry facilities in the employment contract for Seasonal Agricultural Workers from Mexico.The terms of these contracts are negotiated between the Canadian government and the home country of each worker.

A federal official said employers who don’t comply could be penalized or banned from the program.

However, the standards of the accommodations provided to these workers are enforced and monitored by the provincial government, with some inspections by the region’s public health agency.

And the rules about laundry are different at every government level.

According to the contracts issued to all participants in the program, “laundry facilities, including an adequate number of washing machines and where possible, dryers,” should be provided to the worker by the employer.

Credit: Supplied

This is what it says about laundry facilities in the employment contract for Caribbean Seasonal Agricultural Workers.The Niagara Region public health department gives its health inspectors a different set of standards when they’re assessing worker bunkhouses for compliance.

Niagara’s public health department inspects upward of 430 bunkhouses each year.

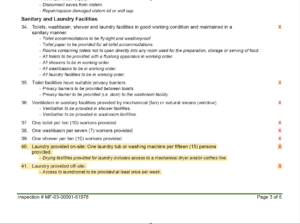

Credit: Supplied

Niagara Region Public Health Temporary Foreign Worker Housing Inspection Report.Public health has not updated its guidelines for worker housing standards since 2010.

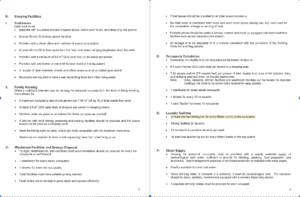

Credit: Supplied

Seasonal Farm Worker Housing Guidelines.Those guidelines say bunkhouses need “at least one laundering tub for every 15 bunks or the equilvalent.”

Peter Jekel, manager of environmental health for Niagara’s public health department, said, “These are guidelines that are provided across the province.”

According to the inspection report public health uses, the workers’ employer should provide “one laundry tub or washing machine per 15 persons.”

Jekel described laundry tubs as “deeper tubs with ribbed edging that you can sort of scrub your clothes on. Similar to a washboard. And has hot and cold running water.”

“That would be considered a laundry tub,” he added.

According to the province, if bunkhouses are not equipped with the appropriate laundry facilities, the employer must provide weekly transportation to the nearest laundromat.

“If the laundry tub is provided to the workers then there is not a requirement for the employer to provide transportation to the laundromat,” said Jekel.

Some bunkhouses lack dryers as well, so many workers will hang their clothes out to dry in the sun.

“They have to provide a line, which they do have a clothesline, but if it’s raining or if it’s cold, it just freezes,” said Jane Andres, a prominent Niagara-on-the-Lake advocate for migrant workers.

Mila Roy, a spokesperson for Employment and Social Development Canada, said “concerns have been raised about the safety of dryers in all circumstances.”

When The Lake Report asked what she meant by that, she didn’t respond before publication.

The guidelines are just that – guidelines. Anything more provided is out of the goodness of an employer’s heart, said Andres.

“This is something that the guys have been talking about as long as I’ve been getting to know them,” she said.

Reid, who was due to return to Jamaica the day after he was injured, was hurt while cycling back to P.G. Enns Farms after doing his laundry in St. Catharines. There are no laundromats in NOTL.

Andres estimated Reid’s roundtrip on his bike was about 16 kilometres.

Not having regular laundry facilities for workers who toil in the fields comes as a surprise to many.

“Never expected this in a first world country,” another worker from P.G. Enns Farms told Kit Andres from the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change, in a text message from 2020.

He had to hand-wash his clothes or go to the laundromat, he said.

“I think if you comment on those things the boss will not make you come back (next) season, so everyone keeps quiet,” he told Kit Andres.

According to the federal government’s standards, farms without washers need to provide weekly transportation to a laundromat.

“Employers found to be in non-compliance could face a penalty or be banned from the program,” said Roy.

But according to provincial public health standards, tubs are considered sufficient for a worker’s laundering needs. And regional public health inspectors abide by that standard.

It’s hard to fine a farm when the province and nation disagree over what’s required.

Foreign Agricultural Resource Management Services (FARMS) is a federal operation that plays an administrative role in the seasonal worker program.

Farmers submit a Labour Market Impact Assessment (LIMA) along with the mandatory housing inspection report. FARMS vets the application then sends it off to Service Canada.

Every employer must fill out an assessment, which will determine if there is a need for a foreign worker.

Some public health units have modified the seasonal farm housing guidelines, senior communications adviser Anna Miller from Ontario’s Ministry of Health said in an email to The Lake Report. No details were provided.

When Ken Forth, president of FARMS, was asked why the federal contracts don’t match up with the provincial housing guidelines, he commented, “We’ve got a dumb country.”

“Local health units actually have the ball,” he added.

When the province’s health ministry was asked the same question, an official said to contact the federal government.

As for whether FARMS has ever raised concerns over the discrepancies between the accommodation standards in the contracts and the compliance requirements enforced by public health inspectors, Forth said, “Probably not.”

“That wouldn’t be our place to. That’d be the foreign country (who) should do that,” he added.

Forth said he doesn’t make the contracts. He reads them.

The lack of collaboration between the provincial and federal governments is making the lives of seasonal workers more difficult when they are in Canada.

“I do know that Service Canada has talked about some national housing standards,” said Niagara public health’s Jekel.

“And it was during the height of COVID that they had started those, at least comments being made, but subsequent to that we have not heard anything at all regarding that,” he said.

“I think it’d be nice if we had some guidelines that were updated.”

Since the December 2021 “What We Heard” report, which outlined some of the concerns regarding employer-provided accommodations, Employment and Social Development Canada has been working on new program requirements that address health and safety concerns.

The 2021 report covered issues like overcrowding, health and safety, inspections and access to resources.

Roy said the issue is “complex and multi-jurisdictional in nature.”

Forth called the “What We Heard” report a “joke.”

“I was at some of those meetings. You had screamers there, just screaming stuff that wasn’t true,” he said.

“Like those groups that are around, they’ll tell you that farmers don’t have WSIB or OHIP and all that,” he added.

He said WSIB is a “no-fault system.”

“And that means that if you’re in a designated occupation, like agriculture is, that workers are covered. Period,” he said.

Roy said the government can’t set national housing standards by itself and because of that, in March a team was put together that includes the federal government along with provinces and territories to work on the issue.

A roundtable was also held in July, which focused on housing standards. However, that could take a few years to implement.

“Employment and Social Development Canada expects to be ready to communicate program changes in early 2023, with implementation anticipated as soon as 2024,” said Roy.

Though every case is different, some workers may be in for a shock when they arrive at bunkhouses only to find a laundry tub and a clothes line.

Roy noted there’s a tip line workers can call to lodge a complaint. Those calls are taken seriously, she said.

The calls are free from any Canadian phone line. However, many workers don’t have Canadian phones.

Sometimes workers aren’t even told about the tip line, said Kit Andres.

The tip line is operated by live agents who offer services in more than 200 languages.

“These live agents can help workers communicate situations of mistreatment or abuse, and provide additional education for workers on their rights,” said Roy.

However, that’s hard to do when the guidelines are different across the board. In many cases, the workers don’t speak up for fear of being sent home as well.

“These calls for change need to be coming from the community. That pressure can’t just stay on the workers to speak up because that power is taken away from them,” said Kit Andres.