Penny-Lynn Cookson

Special to Niagara Now/The Lake Report

A naughty friend with a twinkle in his eye recently asked, with regard to this column, “When are you going to do erotica?”

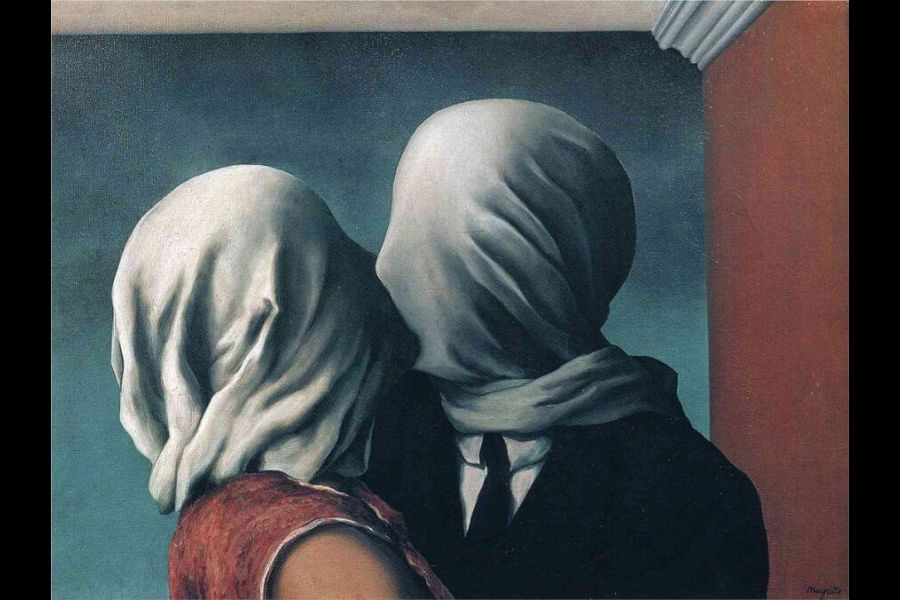

I laughed, believing that the family-friendly pages of The Lake Report might not be suitable for such a probing subject. But then the idea of erotica in its mysterious ways, the sensuous and subtle, as opposed to aggressive and blatant, captured my imagination and into my mind slid René Magritte’s masked lovers.

What is there to see? In front of two primary painted walls of blue and red, cool and warm, the lovers kiss through white cloth tightly wrapped across their faces but falling into loose folds around their necks to the backs of their heads. The man is dominant, leaning forward slightly as the woman tilts her head up submissively for the kiss.

They are well-dressed, the man in a dark business suit, white shirt and tie, the woman in a red dress with white piping. Are the colours significant? Blue for calm, white for purity, red for passion, black for death?

The only bare skin is the woman’s upper arm and in its foreground position to the viewer, it becomes strangely suggestive, evocative, waiting to be touched, a reminder of that momentary flick of a woman’s ankle usually hidden under long skirts that sent men into a tizzy at the end of the 19th century.

The 1920s were the liberation era of the smoking hot, cropped hair “flappers” waving cigarette holders in their short sleeveless dresses as they danced the Charleston with abandon while ushering in new values. All this was soon to come to a crashing end with the decade ahead and there is something in this image that suggests the tentative hesitancy, a desire for an elusive intimacy, the unknown of what lies ahead, so reflective of our own time.

Kissing is memorable in our western art icons of Rodin’s sculpture of embracing lovers and Gustave Klimt’s lovers bedazzled by desire in golden garments. Hollywood kisses were seared into our romantic dreams, changing with generations in movie houses now altered by at home streaming, Netflix and porn.

The smouldering Rudolf Valentino and swashbuckling Errol Flynn evolved to the thwarted mature love of Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman in “Casablanca” and on to the young, passionate, windswept kisses of the doomed lovers of ‘”Titanic.”

However, there are things we should know. Kissing helps us choose our mates. The swapping smooch uses 146 muscles and introduces 80 million new bacteria. Gross to some.

According to a recent Washington Post article on a University of Nevada study of kissing, in North America 55 per cent of us romantic-sexual kiss, 45 per cent of us kiss in a nonromantic-sexual way.

On romantic-sexual kisses Europe is 70 per cent, Asia 73, Oceania 44 and the Middle East 100. But romantic kissing is not “on” in Central America and is not the norm in Africa at 13 per cent or South America at 19 per cent.

Kissing is a very strange thing to some. But how to kiss? Lips? Noses? Tongue? A peck on the cheek? The air kiss? One cheek, two cheeks, three cheeks, even four? Or the always swoon-worthy respectful kiss on the hand? Or sadly, no kisses at all during COVID?

And so, back to Magritte. What were his intentions? What should we take away from this strange masked kiss? Frustrated desire? Fabric acting as prevention to passion? Intimacy denied? Or a subtle question as to whether we ever can know the true nature of those we love?

René Magritte was born in Belgium in 1898 and became a leading exponent of Surrealism. Juxtapositions of the ordinary, the strange, the erotic, the ambiguous and of humour appear in his work. By the time of his death in Brussels in 1967, he had achieved a great influence on Pop art and advertising.

The man in the bowler hat, the pipe, the floating apple or rock in the room remain familiar images that continue to perplex and delight.

On whether his continual obscuring of the faces of his subjects was due to the trauma of his mother’s death by suicide, Magritte disagreed and stated that his “visible images conceal nothing … they evoke mystery and, indeed, when one sees one of my pictures, one asks oneself this simple question, 'What does it mean?' It does not mean anything, because mystery means nothing either. It is unknowable.”

Penny-Lynn Cookson is an art historian who taught at the University of Toronto for ten years. She was also head of extension services at the Art Gallery of Toronto. See her lectures on “Landscape and Memory’”on Zoom at the Pumphouse Arts Centre, Aug. 4 to 25. Registration is free.