The town of Niagara-on-the-Lake has been described as having the greatest concentration of surviving British Colonial architecture built between 1813 and 1860 of any municipality west of Quebec.

It would be nice to think that this was due to an ongoing, focused preservation effort by decades of townsfolk.

But, when considering Niagara-on-the-Lake’s record of formally protecting this legacy, its survival seems to have been more of a happy accident.

Now, to be clear, there have always been resident individuals who have worked, and continue to work, tirelessly to preserve the town’s history and built heritage. There are also those who have voluntarily chosen to designate their home.

However, on the other side of the fence, there were (and are) those rigorously opposed to formal heritage protection — while the remainder, likely the majority, are fence-sitting neutrals.

To demonstrate this contention, let’s return to 1978 when the town established a Local Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee to advise council on heritage matters.

Over the next eight years, the committee members assisted property owners in the Part IV designation of 20 properties.

Moreover, they recommended and directly supported the creation of the Queen-Picton Heritage Conservation District under Part V of Ontario’s Heritage Act — the district plan’s author, Nicolas Hill, acknowledged their contribution.

In 1986, when council approved its establishment, Niagara-on-the-Lake’s Conservation District was one of only 20 in the province (counting each of Ottawa’s Sandy Hill districts separately) — as of March 2020, there were 134 districts.

It should be noted that municipalities like Goderich, Brantford, Kingston, et al., continued to create new heritage conservation districts, while Niagara-on-the-Lake has been frozen in time vis-à-vis any heritage preservation commitments.

I was always curious why the boundaries of our district were so constrained and somewhat odd — including one side of Prideaux and Johnson streets but not the other, when both sides of each street were (arguably) in possession of equal heritage value.

Several years ago, I posed this question to one member (now deceased) of the committee during that undertaking.

His answer was telling when he replied with some bitterness, “We got what we could, but certainly not what we wanted. I thought of it like a beachhead, if you will, something we could go back and properly expand later. More fool I.”

In fact, the committee – underwritten by a thorough research report – did go back to council in 1996 with a recommendation to expand the boundaries of the heritage conservation district to include all areas from Front Street to Gage Street, extending down to encompass the dock area.

Council responded by passing a bylaw to commission the study required to underwrite the expansion but – for political reasons on which we can only speculate – failed to direct town staff to budget the funds required.

In a staff report to council from May 2014 entitled “Official Plan Review – Heritage, Arts, and Culture Issues Report,” staff stated: “While council passed a bylaw to study the area, no further work has been done, although the bylaw has not been repealed.”

Having established the town’s first conservation district in Old Town, in 1988, at the behest of some residents, the Local Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee shifted part of its attention to the historic village of Queenston.

Significant research and study by committee members resolved into a recommendation for council to consider creating a heritage conservation district in Queenston.

The council of the day thereafter commissioned a heritage conservation district study, which was completed in 2002 and supported the establishment of a district.

Unfortunately, it appears that the level (or form, or both) of community consultation and dialogue was lacking in the process.

The result was an acrimonious rejection of the proposed district by a significant number of village residents and council did not move ahead with its creation.

In the early years of this century, NOTL’s conservation advisory committee partnered with the Niagara Foundation and the Niagara Historical Society, assisted by architects William Thomas and James Cooper, with an overture to the federal government to establish a National Historic Site (with boundaries significantly larger than the Queen-Picton Heritage Conservation District) in Niagara-on-the-Lake.

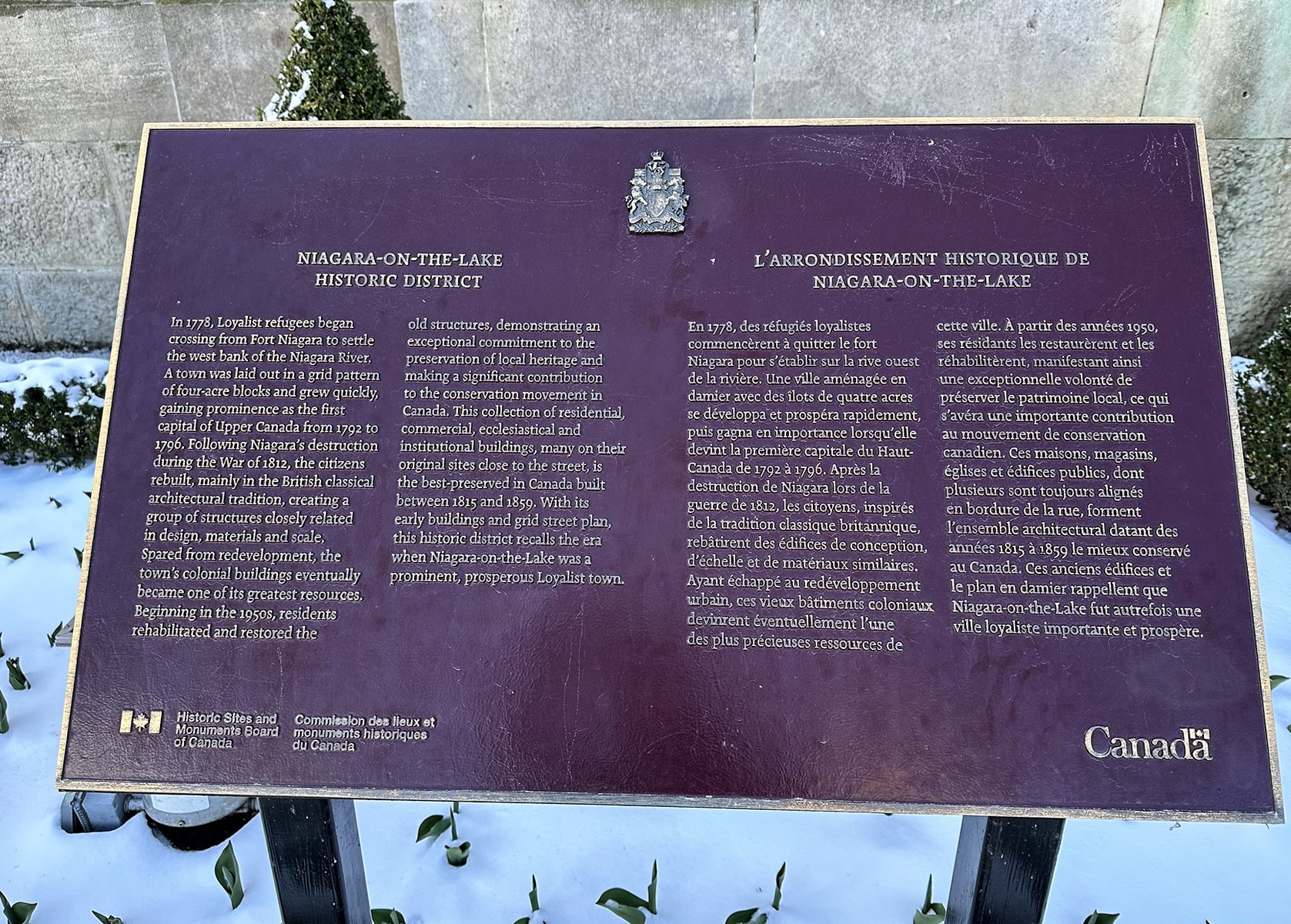

While rigorously scrutinized by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, this application – with its supporting documentation – was accepted without modification.

In 2004, the federal government created the Niagara-on-the-Lake National Historic Site — one of a mere handful of sites across the country which encompasses a community as opposed to a specific building or installation.

On the Parks Canada Directory of Federal Heritage Designations website, it wrote the following (the words are their’s … but I applied the italics):

“Niagara-on-the-Lake was designated a national historic site of Canada because: it possesses the best collection of buildings in Canada from the period following the War of 1812, that is from 1815 to 1859, especially houses, designed in the British Classical tradition as well as vernacular buildings with features derived from this tradition; as a whole, the buildings and landscape components, including the placement of houses close to the streets that define the four-acre-block grid, speak to the era when Niagara-on-the-Lake was a prominent and prosperous Loyalist colonial town; and, the buildings within the historic district speak to the conservation movement in Canada, as many citizens have taken the initiative to have these buildings rehabilitated, renovated and/or restored to highlight their heritage character, expressing an exceptional commitment to the preservation of their town’s heritage.”

It is so sad that in Canada — unlike many other countries in the world such as the United Kingdom and the United States of America — the designation of a National Historic Site confers only a recognition of historical importance evidenced by a plaque and website notation, but does not carry with it any legislative protections.

At this point, I am ironically reminded of the Lennon-McCartney lyrics of the Beatles song, “The Long and Winding Road.”

Still, what things can we draw from this 50,000-foot level glimpse into the last 40 years of NOTL’s record on heritage protection?

First, in a town that holds a remarkable amount of surviving built heritage, the efforts to protect that history have primarily been driven by private individuals and groups.

Town councils have occasionally been obstructionist, at other times laissez-faire, and almost without exception consistently failed to make action vis-à-vis heritage preservation a priority on a non-political basis.

Second, to date, there has been a serious lack of readily available information – in a straightforward, easily read form – concerning heritage protection.

Nor, insofar as I am aware, has there ever been a serious, ongoing community outreach program to provide a forum in which NOTL property owners can gain an accurate picture of heritage protection.

Hence, there has been and still exists both apprehension and misunderstanding in the minds of many folks regarding designation and conservation districts.

It’s high time that we correct these and other mistakes of the past.

NOTL citizens deserve to enjoy the financial, cultural and aesthetic benefits conveyed by formal heritage protections.

Brian Marshall is a NOTL realtor, author and expert consultant on architectural design, restoration and heritage.