Elizabeth Masson

Exclusive to The Lake Report

Did St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church’s Manse harbour runaway slaves during the pre-Civil War era? Very likely.

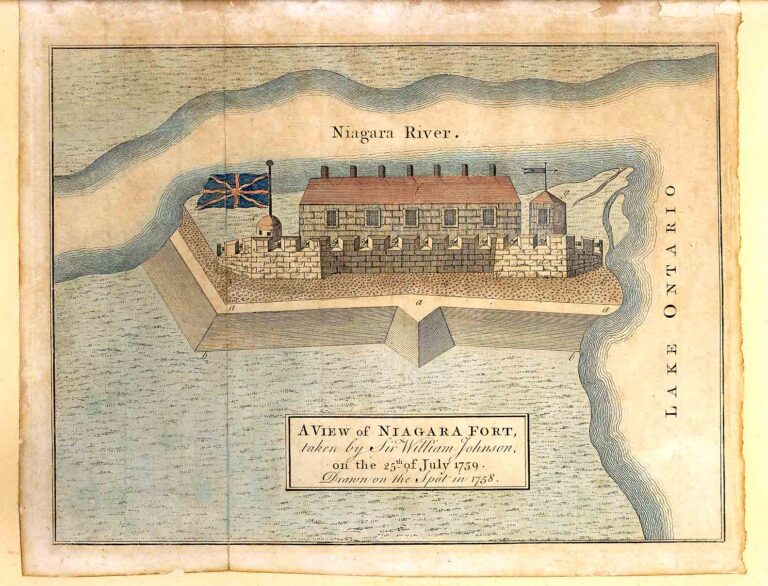

The first Presbyterian church building on Simcoe Street was built in 1795. However, during the War of 1812, it was burned by the invading American army in August of 1813.

The school house, built in 1802, on the northeastern part of the property, survived until the 1940s. It was located on Gage Street behind the current parish hall, which, incidentally, was originally a Camp Niagara building, moved to the site in the 1940s and was subsequently bricked over.

Following the War of 1812, worship services were held in the school house and the church remained without a minister until, in 1829, Rev. Robert McGill was sent from Glasgow. It was at this point that the church, known as the “Presbyterian Church in Niagara,” changed its name to St. Andrew’s.

And with the arrival of McGill, fundraising started in earnest to rebuild the church. In 1831, the cornerstone was laid on the same spot on which the former church had stood. The brick building was designed in the Greek-revival style and based on the Temple of Thesus. The tympanum over the church entryway has a gilt sunburst, unusual for a church since it was a pre-Christian symbol for the sun god Apollo.

McGill had the current Manse built with his own funds in 1836. When he left in 1845 to accept a posting in Montreal, it was purchased by the congregation with a legacy of 750 pounds left by John Young, the founder of Youngstown, N.Y., and a member of the church for many years.

The word manse comes from the Latin and is used to describe the house of a minister; it is customarily used for the home of Presbyterian ministers.

The Manse was built in the Georgian style and has a hipped roof and symmetrical facade. A fanlight and sidelights decorate the central entry to this home, which is made of rose-coloured brick and cut stone.

Peter Stokes’ description of the house in his 1971 book about Niagara-on-the-Lake says, “This is a neat hipped roof house of five bays, a centre door with sidelight and fanlight, a storey and attic over a high basement in height.”

The windows have original interior shutters and three fireplace mantels are hand-carved. The basement originally included a kitchen, bake ovens and a dumbwaiter that went up to the dining room.

It is likely that runaway slaves from the United States stayed in the basement of the house after crossing the Niagara River. As is emphasized in the newly released Harriet Tubman film, the slaves, sometimes travelling for over six weeks, followed the North Star at night and believed that they were going to the Promised Land, which was Canada.

These slaves, most of whom could not read or write, were deeply religious. So, it is likely that once they had crossed the Niagara River and heard that a church minister in Niagara would give them refuge, runaway slaves would have headed in the direction of St. Andrew’s Manse.

Incidentally, the chapel in St. Catharines, which was built by Harriet Tubman and other blacks in the community in 1853, is briefly shown in the movie. It is the Salem Chapel of the British Methodist Episcopal Church on Geneva Street. Services are held on Sundays at 11 a.m.

The first blacks to settle in the area of St. Andrew’s Church were two freed black men, brothers James and Humphrey Waters in 1796. The school house, next to the church, held classes for blacks as well as whites up until about 1850.

Many freed and runaway slaves lived in the vicinity of the Manse. Between William and Anne streets and bounded by Regent and Simcoe, 41 of the one-acre lots were owned by blacks. In 1842, the combined population of the township and town of Niagara was 3,900 and five per cent were black.

One can see at the back of the ground floor of the Manse, a small door which supposedly led to the basement where the freed slaves were allowed to stay until they could find shelter elsewhere.

Robert McGill’s daughter, Janet, who was born in the Manse, subsequently married Rev. J. B. Mowat, brother of Sir Oliver Mowat. Rev. Mowat was minister of St. Andrew’s from 1849 to 1858. Mrs. Mowat, unfortunately, died within a year of moving back to her childhood home. Surprisingly, she is not buried in the churchyard across the street.

Rev. Mowat was well-loved by the congregation and was commended for finding time on Sunday afternoons to preach to a black congregation. There were Methodist and Baptist churches in town at that time, both of which had black members. Soon after his wife died, he was appointed professor of oriental languages and biblical criticism at Queen’s University.

In 1887, a two-storey brick wing was added to the Manse and the first furnace replaced the fireplaces in 1892 at a cost of $85. The basement kitchen was moved to the main floor in 1937.

In 1933, the church’s financial situation became difficult, repairs on the church were needed, and the Manse was mortgaged for $1,000. In January 1940, Emma Houghton discharged the mortgage.

Substantial work was done in 1958. A student from the University of Toronto architecture department took photographs of the restoration and also made measured drawings.

Notable is the fact that the front porch was covered and had columns supporting it. These columns must not have lasted long because a photo of the Manse in the “History of St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church 1791-1975” does not show them. Further work was done on the exterior of the Manse prior to the arrival of the present minister, Rev. Virginia Head.

Elizabeth (Betsy) Masson has been a research volunteer at the Niagara-on-the-Lake Museum (formerly the Niagara Historical Society Museum) for 15 years.

Information on what was called the “Colored Village” in Niagara comes from “Slavery and Freedom in Niagara” by Michael Power and Nancy Butler, with research by Joy Ormsby. It is available at the Niagara-on-the-Lake Museum shop on Castlereagh Street.

The Colored Village will be described in a later installment of Niagara’s History Unveiled.

More Niagara’s History Unveiled articles about the past of Niagara-on-the-Lake are available at:

www.niagaranow.com