Are you ready to party?

As we hesitantly crawl out from the constraints of our restricted social lives of the past three years, one example of an over-the top banquet may serve to astonish. It’s all about roses.

Beautiful, historic, symbolic, coveted, admired – roses have power. We gift them as expressions of love, friendship, celebration or sorrow.

They have also been symbolic of political battles for supremacy, such as the 15th century English War of the Roses. Intrigue, controversy and veiled meanings have been a part of the aesthetic world story of the rose since its first wild fossil was identified as 35 million years old.

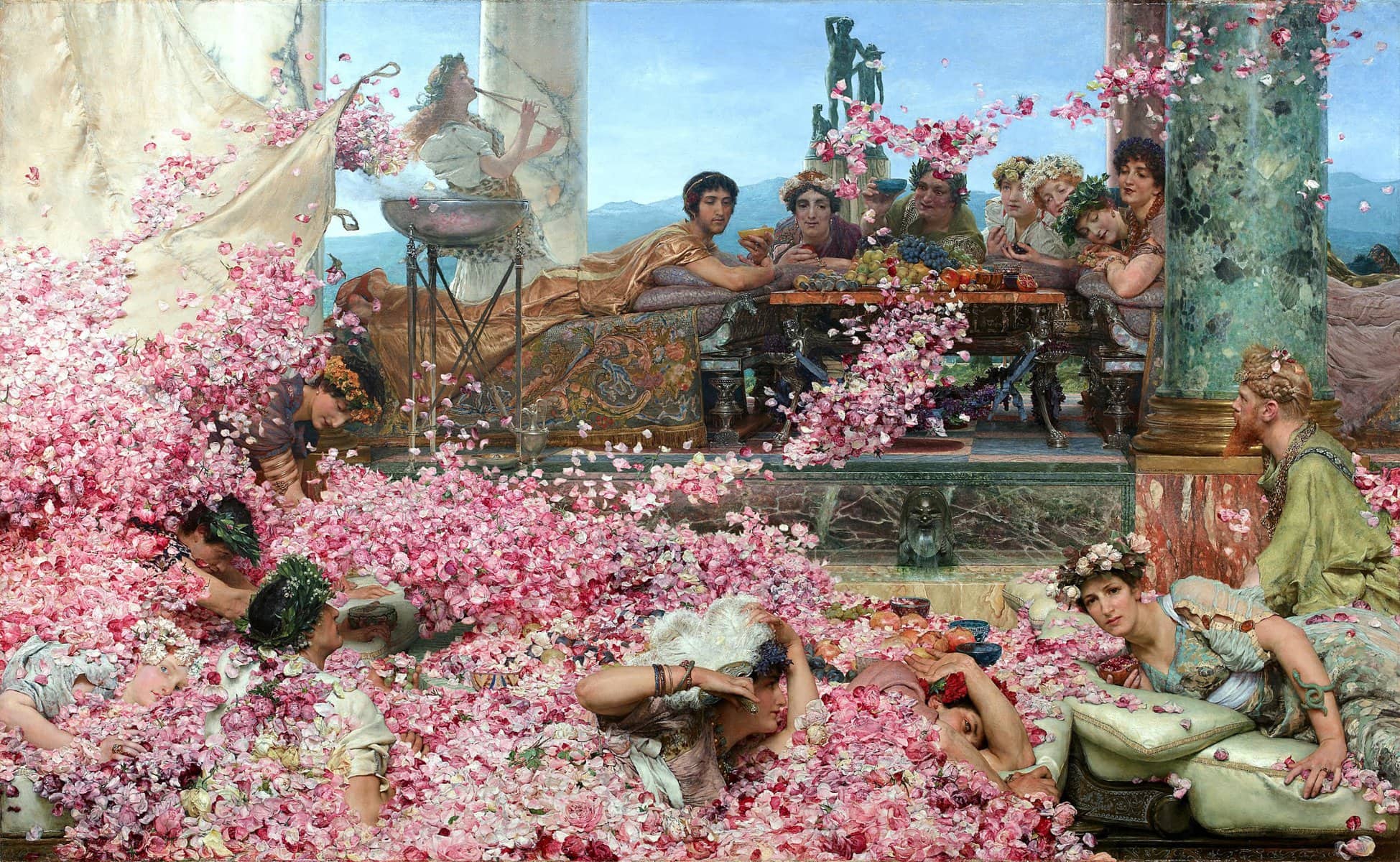

In “The Roses of Heliogabalus,” Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema has taken the ancient Roman sensuous obsession with roses to its extreme in a painting that met the late 19th-century prudish Victorian desire for “wicked” paintings that combined academic historical accuracy with salacious scenes.

In the banquet of all banquets, the young Emperor Elagabalus, wearing a gold silk robe, lies on a fine tapestry, delicately holding his glass of wine as he dispassionately observes floral carnage as his guests are smothered to death by a cascade of pink rose petals released from a false ceiling over their heads.

Being inebriated and spent from an excess of food, wine and sex, they seem not to mind their fate. A maenad musician, cult follower of the god of wine Dionysus, whose sculpture is behind Elagabalus, plays the double pipes, inciting the guests to greater ecstasy.

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, known as Elagabalus, is considered one of the worst Roman emperors by the Historia Augusta and Gibbons “Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire.”

He ruled a mere four years, 218-222 AD, as his wild, depraved, oversexed, vicious behaviour of executing anyone who censured him, his five marriages and four divorces including to a Vestal virgin, and delight in wearing makeup and women’s clothing, became too much even for his grandmother who arranged for his assassination by his Praetorian Guard.

He was 18 when he was killed. Elagabalus has been relegated to “damnatio memoriae,” erasure from public record as a disgraced person of note.

When “The Roses of Heliogabalus” was commissioned by Sir John Aird in 1888, roses were out of season so Alma-Tadema imported them weekly for the four months it took to complete the painting.

It was exhibited to great acclaim but interest in his work declined dramatically with his death in 1912 and has now been re-evaluated in recent years for its importance within 19th-century British art.

As we enter spring with plans to prune our rose bushes and entertain, perhaps not with peacocks tongue, camels hoof and fried dormice, we can smother our guests with kindness and regale them with further stories of the power of roses.

Penny-Lynn Cookson is an art historian and writer. See her live lecture on the “Power of the Rose” on Saturday, March 25 at 3:30 p.m. at RiverBrink Art Museum in Queenston.