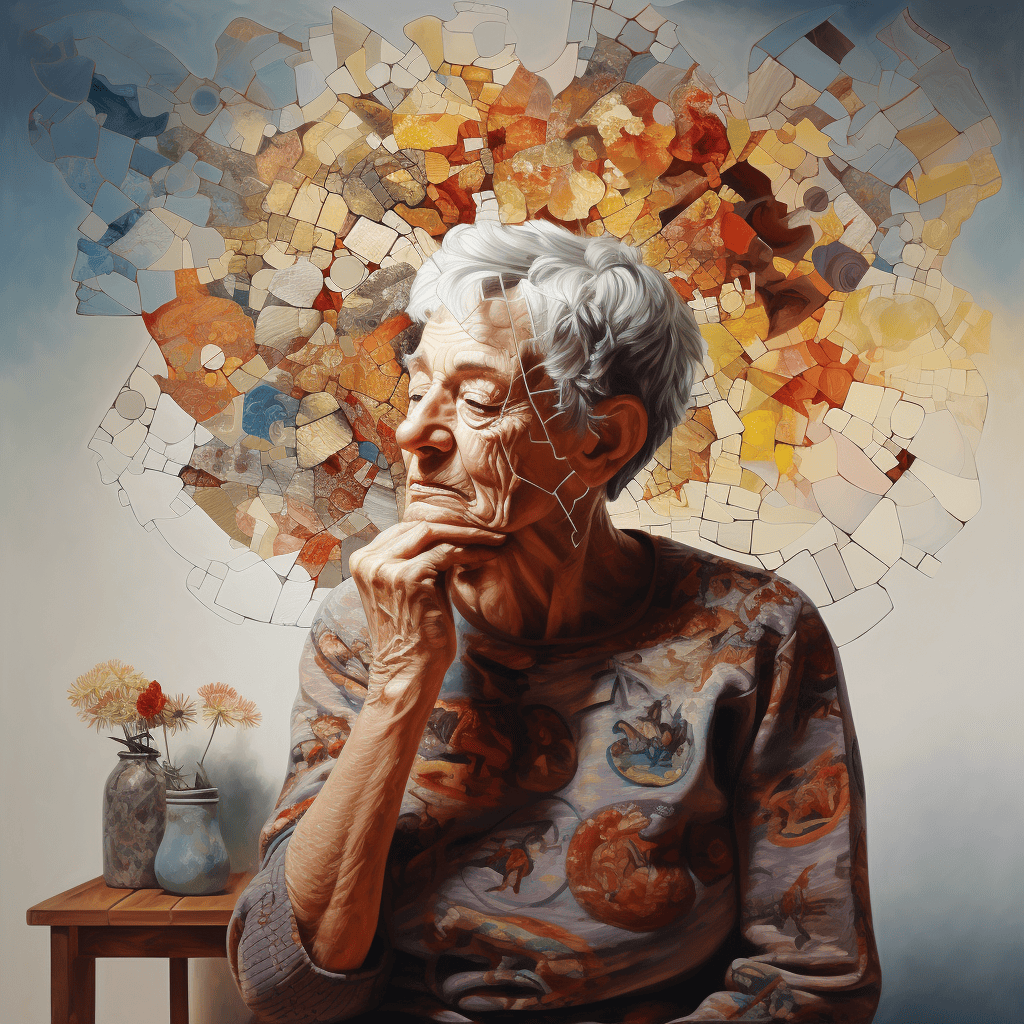

Were any disease to be called cruel, Alzheimer’s disease would surely be near the top of the list.

It wipes out a lifetime of memories, relationships with long-time partners and friends and toward the end, a sense of self. And for many, the course goes on for years, initially at home, and later in long-term care facilities, before the end.

Unlike cancer, heart disease and stroke where major advances have been made in prevention and treatment, until the last few years there was little hope for patients with Alzheimer’s.

What hope did exist was usually a flickering affair, each successive flicker collapsing in the face of the failure of this or that drug to slow – never mind stop – the relentless cognitive and behavioural decline associated with the disease, to say nothing of often-serious side effects associated with anti-amyloid drugs.

The central challenge with Alzheimer’s is that, like other neurodegenerative diseases, the condition progresses silently for as long as two to five decades before the earliest symptoms manifest.

During that long asymptomatic period, abnormal proteins such as beta-amyloid accumulate in the brain’s extra-cellular space forming inflammatory, destructive plaques, and the tau protein creates tangles within neurons, which spread from neuron to neuron.

The result is the destruction of neurons and the vast networks of connections between them, the clinical effects of which go unnoticed for a long time – although, PET scans reveal the deposits of beta-amyloid and tau, and analyses of the cerebrospinal fluid and blood, show traces of the underlying chemical products in the disease.

The last decade of clinical trials employing monoclonal antibodies designed to target beta-amyloid revealed that clinical benefits are minor, even if PET scans show striking reductions in beta-amyloid.

That’s the reason why following two very expensive Phase 3 trials, the medication Aducanumab initially failed to receive approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Biogen lobbied the FDA to reverse its decision based on the company’s claim that following their review of the trial data, Aducanumab had – at the highest dose level – significantly slowed cognitive decline.

In the face of this and other pressures, the FDA conditionally approved Aducanumab – a mistake, in my opinion.

Then, early this year, the New England Journal of Medicine published the results of a Phase 3 trial with Lecanemub, a similar monoclonal antibody designed to target a different part of the beta-amyloid molecule.

Here, the evidence for slowing the rate of cognitive decline was statistically significant but modest at best, and there were serious side effects. Like Aducanumab, the latter took the form of brain swelling and/or multiple small hemorrhages and several related deaths.

That both Aducanumab and Lecanemub clear the brain of much of the beta-amyloid burden is obvious. The question is whether these amyloid-clearing drugs significantly slow the decline in cognitive function in a way that would be apparent to caregivers and patients. That’s a much tougher question to answer.

Some scientists believe the real culprit is tau, not beta-amyloid. Hence, a renewed interest by many scientists in clearing the brain of tau.

That might be a challenge: unlike beta-amyloid, tau tangles are located inside neurons, where the tau may prove less accessible to monoclonal antibodies.

The importance of tau is supported by experimental models, which suggest that only when tau levels increased was there evidence of cognitive impairment.

The evidence suggests several paths forward:

Those at risk for developing Alzheimer’s should be identified as early as possible based on their family histories, genetic tests, PET scans and blood and possibly cerebrospinal fluid testing.

Dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s cases would be prime targets for prophylactic treatment because all these patients develop the disease usually two-three decades before other far more common forms of Alzheimer’s.

Treatment should begin before symptoms begin.

For any treatment to be considered for use during the asymptomatic period of the disease, any drugs used – whether alone or in combination – must be shown to be safe, well-tolerated, and effective in preventing the accumulation of tau and beta-amyloid in the brain, and most important, must be shown to prevent the later development of cognitive impairment.

Vaccines should be developed using modern RNA technologies to target specific sites on the tau and beta-amyloid molecules.

Combinations of vaccines and monoclonal antibodies should be explored for use early in the subclinical course of the disease.

Gene editing should be developed to delete or correct high-risk genes to reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

We are well short of achieving those goals, but the groundwork has been laid. The number of clinical cases is so high that urgent action is needed, especially by identifying and treating cases before cognitive impairment becomes apparent.

Similar reasoning may hold true for other neurodegenerative diseases.

My opinion, of course, but it makes sense based on the published evidence so far.

Dr. William Brown is a professor of neurology at McMaster University and co-founder of the InfoHealth series at the Niagara-on-the-Lake Public Library.