In the springtime of the initial four years we lived in Niagara-on-the-Lake, a female fox with a decided limp in her left leg took up residence in the culvert beneath our driveway.

With her new cubs — all cute, frisky, and playfully leaping straight up or tumbling into one another or mum — they were fun to watch.

But when the fifth spring came, no limping mother and cubs were to be seen around our home, although sightings of a fox with a limp were reported from different places in NOTL that year.

Maybe she wandered out of town, or a coyote got her, but whatever happened she was never seen again.

In the same time frame, my wife and I sometimes visited friends who owned a small island in Haliburton visited annually by a pair of loons.

They managed not only to find the same small island every year but refashioned and spruced up the previous year’s nest for their coming family.

Those anticipated annual visits went on for several years until they too stopped, and like the female fox, we’ll never know what became of the pair of loons.

Those loons were amazing: they managed to find the same nesting spot year after year.

They also travelled much farther than I did when I flew back and forth initially from London, Ont. or later from Boston to Stanhope Municipal Airport in Haliburton County, using GPS – or before that, Loran – to find my way even when visibilities and ceilings were poor.

So, hats off to those loons and all migrant birds that find their way without fancy electronic tools.

Migrations are common in nature. Examples include insects like monarch butterflies, fish such as salmon, even great white sharks and mammals from humpback whales to caribou.

The longest annual distance travelled by a single species apparently belongs to the Arctic tern: a round trip of up to 59,000 miles each year, according to The Wildlife Trusts, flying from the Arctic to the Antarctic in the winter.

Most of those migrations are related in some fashion to annual changes in weather and longer-term climate shifts, which influence the availability of food and water.

From the time when they evolved 200,000 to 150,000 years ago in Africa, modern humans dispersed repeatedly and travelled widely, reaching western Europe 55,000 years ago, Australia 60,000 years ago and the Americas 15,000 years ago.

Neanderthals also dispersed but to the best of our knowledge, never beyond Eurasia.

Earlier still, homo erectus, which in successively larger-brained versions, lasted the longest of our ancestral homo species (1.8 million to 100,000 years ago), was called the “traveller” by archeologist Mary Leakey for good reason: erectus, in later bigger-brained versions, managed to reach much of Eurasia, including what is now China and Indonesia.

Leakey also called them dimwitted because they fashioned the same hafted axes with little in the way of improvements over their long tenure – despite a brain twice the size it was at the beginning of their time.

Before homo erectus’ time, what about the australopiths, those evolutionary variations on a theme of small-brained, bipedal apes? Did they too, like their homo successors, disperse outside Africa?

The record of Lucy (A. afarensis) and other australopiths is that they stayed in Africa. Only our genus and species, homo sapiens, migrated far and wide, eventually to every continent.

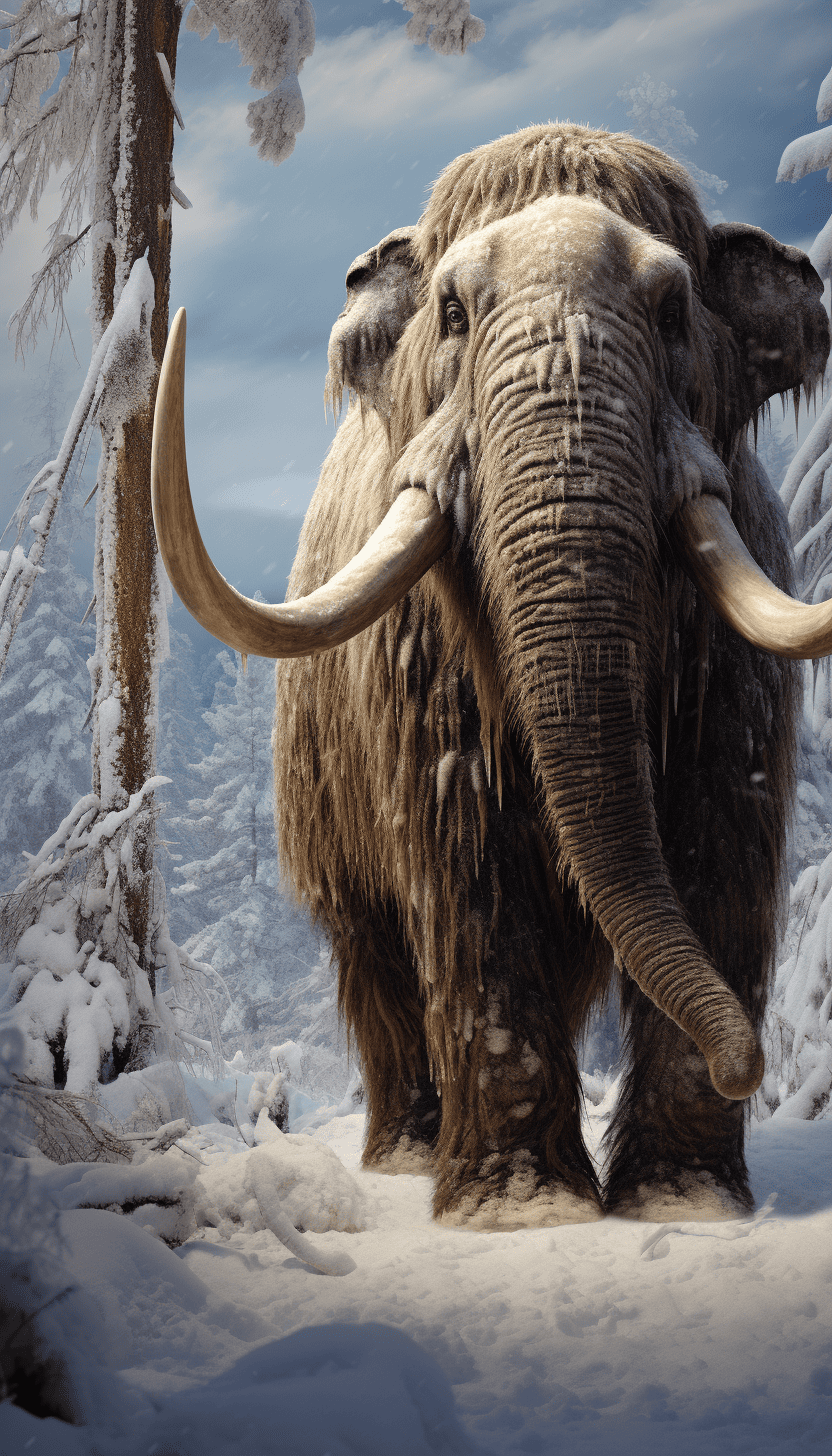

Other species migrated widely, one example of which were mammoths, found throughout Africa, Eurasia and the Americas. The most interesting of which for me was one woolly mammoth named by his investigators as Kik.

Kik’s wanderings in Alaska 17,000 years ago were tracked using his tusks, whose strontium levels reflected the strontium levels in the grass he munched each day and thus the strontium levels in the rocks on which the grass grew.

Tusks grow from the base, the oldest part of which is the tip of the tusk. By cutting the tusk into fine slices and measuring the levels of strontium isotopes in successive slices, like pages in a book, it was possible to match those levels with known strontium levels in rock formations throughout Alaska.

Hence, they could trace Kik’s wanderings throughout much of his life until he died 17,000 years ago at the age of 27, half the average age of most mammoths at death.

The record revealed that when he was young, he travelled widely but as he aged, he travelled less far and less often. Sound familiar?

Returning to foxes, in this case, arctic foxes, a recent study showed that one fox, who was tracked using a GPS emitting device attached to a collar about his neck, managed to cover an astonishing 6,400 kilometres over the 277 days he was tracked.

Probably alone, he somehow managed to find enough food and avoid predators along his marathon trek. Like all long treks by animals, this was impressive

Dr. William Brown is a professor of neurology at McMaster University and co-founder of the InfoHealth series at the Niagara-on-the-Lake Public Library.