In the Nov. 24, 2025 issue of the journal Nature, Blaise Agüera y Arcas, a leading figure at Google, wrote an essay about how we got to where we are with artificial intelligence and much more. He began with a proposition:

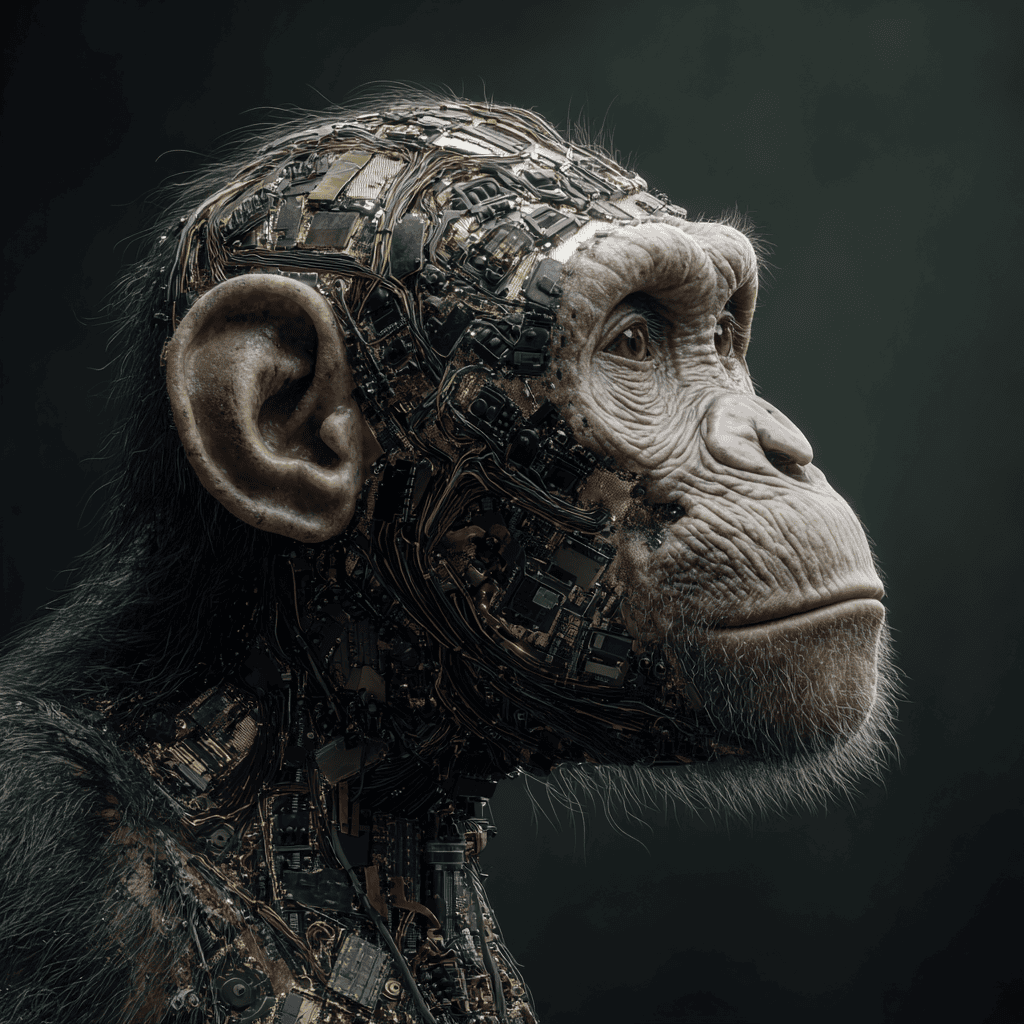

The emergence of what we might call intelligence in AI was not a single giant step but evolved, to borrow a phrase from biology, or, expressed another way more familiar to AI developers, as a result of computational scaling, beginning with simple models for predicting next words or parts of words coupled with increasingly sophisticated large language models and datasets.

By 2025 this process led to versions of AI that are capable of human-like fluency and solving increasingly complex problems that humans find challenging, if not impossible to solve. So much so, as Arcas writes that ”we are running out of intelligence tests that humans can pass reliably, and AI models cannot.” That’s a lot of change for Google and the whole AI field in the last 15 years.

Not surprisingly, given the hype that surrounds AI, a recent article by David Adam in the journal Nature, in which scientists were asked to speculate about the future, suggests that by the mid-century mark or perhaps earlier, AI will reach a level of general intelligence equivalent to or exceeding that of humans, individually and perhaps even collectively.

Going forward, Adam suggests that future versions of AI might become capable of designing and carrying out scientific studies on their own, some of which could rewrite current flawed standard models of the universe and subatomic physics and might, as one physicist put it, even win Nobel Prizes in the process.

One stepping stone to which was AlphaFold2, a version of AI designed to figure out the three-dimensional shapes of proteins and thus how they might work. That effort won the Nobel Prize in chemistry or, rather, two humans did — Demis Hassabis and John Jumper, who were responsible for developing AlphaFold2 (among others at Google).

But it was AlphaFold2 that did the computational work. AlphaFold2 was like a loyal grad student who learned under the tutelage of humans at Google — not human of course, but a student nontheless and perhaps deserving of a share in the prize.

Since then, AlphaFold has been adapted to solve other problems such as predicting weather with a high degree of precision. However, developing general intelligence equivalent to humans is a whole other challenge.

Human intelligence is very broad in scope. It involves social intelligence: figuring out who’s in who’s out and navigating social groups with whom we live, never mind keeping track of and figuring out all the other activities in which we humans engage, the great majority of which would be very challenging to analyze from a computational perspective — the perspective of AI.

AI has a solid place in health care as a loyal companion to humans in the diagnostic and management process because of AI’s unique ability to compile and assess high-quality diagnostic data based on information mined from the best journals and textbooks, as well as data garnered from a high-quality health-care system, such as Harvard’s system or perhaps a Mayo clinic or a group of several similar high-quality sources.

This makes AI invaluable as a source of information for health care professionals however experienced they might be.

One of the reasons AI is so beguiling is its uncanny ‘naturalness’ as I alluded to last week using the example of an AI therapist talking from a smalt phone on the dashboard of a car, with its client, a human who was driving the car. It was the naturalness of the conversational to and fro which was so captivating for the human and frankly me, listening to the exchange. The power in that example came from the large language models which make conversation almost human in tone and composition.

But what is most intriguing to me is the suggestion by Blaise Agüera y Arcas that computation, which is so central to AI, might also have played a key role in evolution.

Arcas suggests, “If scaling up computation yields AI, could the kind of intelligence shown by living organisms, humans included, also be the result of computational scaling? If so, what drove that — and how did living organisms become computational in the first place?”

His answer is straightforward. How else could simple, then more complex, organic molecules have formed in the vicinity of deep sea vents other than in response to physical-chemical and quantum rules operating in the presence of hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, nitrogen ions and atoms to initially create bases, sugar and phosphate groups, then nucleotides and finally strands of RNA over time scales of hundreds of millions of years?

Similar computational rules would have governed the formation of other life molecules essential to the formation of the first simple cells, then complex single cells, followed by multicellular organisms and life as we witness it every day.

Each step in life’s growing complexity involved computation. That’s the message Google’s Blaise Agüera y Arcas makes in his essay and his final point.

Life and AI aren’t so different after all — both are based on computation and both will, in his opinion, co-evolve.

Dr. William Brown is a professor of neurology at McMaster University and co-founder of the InfoHealth series at the Niagara-on-the-Lake Public Library.