Several million years ago, there wasn’t much to differentiate apes ancestral to humans from other mammals whose attention rarely, if ever, strayed beyond their immediate environment and needs, and behavior hardly justified the word “exceptional.”

That was until several hundred thousand years ago when chance and natural selection led to the gradual emergence of a species with big brains capable of increasingly complex symbolic thought and language and creating grand narratives for the origins of the heavens, earth, forces of nature and themselves — a species like no other before them — now solidly set apart by their language and imagination, and surely the beginnings of exceptionalism.

From evolutionary and developmental perspectives, it wasn’t that long before our species became the first to land on the moon and send satellites to the edge of the solar system from which pictures were taken of a tiny planet almost lost in a sea of billions of stars — our island home blue dot as Carl Sagan, so famously expressed it.

In the last 10,000 years, our species domesticated plants and animals and flourished in number to the millions and more recently, eight billion and counting.

With the advent of science our creation stories began to change to reflect our growing understanding of the universe on the largest and tiniest scales, the evolution of life and our own species, and most recently how we might change the genetic destiny of any creature, including ourselves.

Exceptional, now fully justified? Perhaps.

But marvellous as we are, there are caveats. For at the most elemental level, all life discovered so far shares the same core elements and molecules of life from simple cells to us.

For sure, there are differences but there are far more similarities than differences between simple cells and complex single cells and between the latter and multicellular organisms of increasing complexity.

When it comes to mammals, the body systems and organs of all are nearly identical, whether they be the circulatory, respiratory, gastrointestinal, skeletal, immune, endocrine or genito-urinary systems.

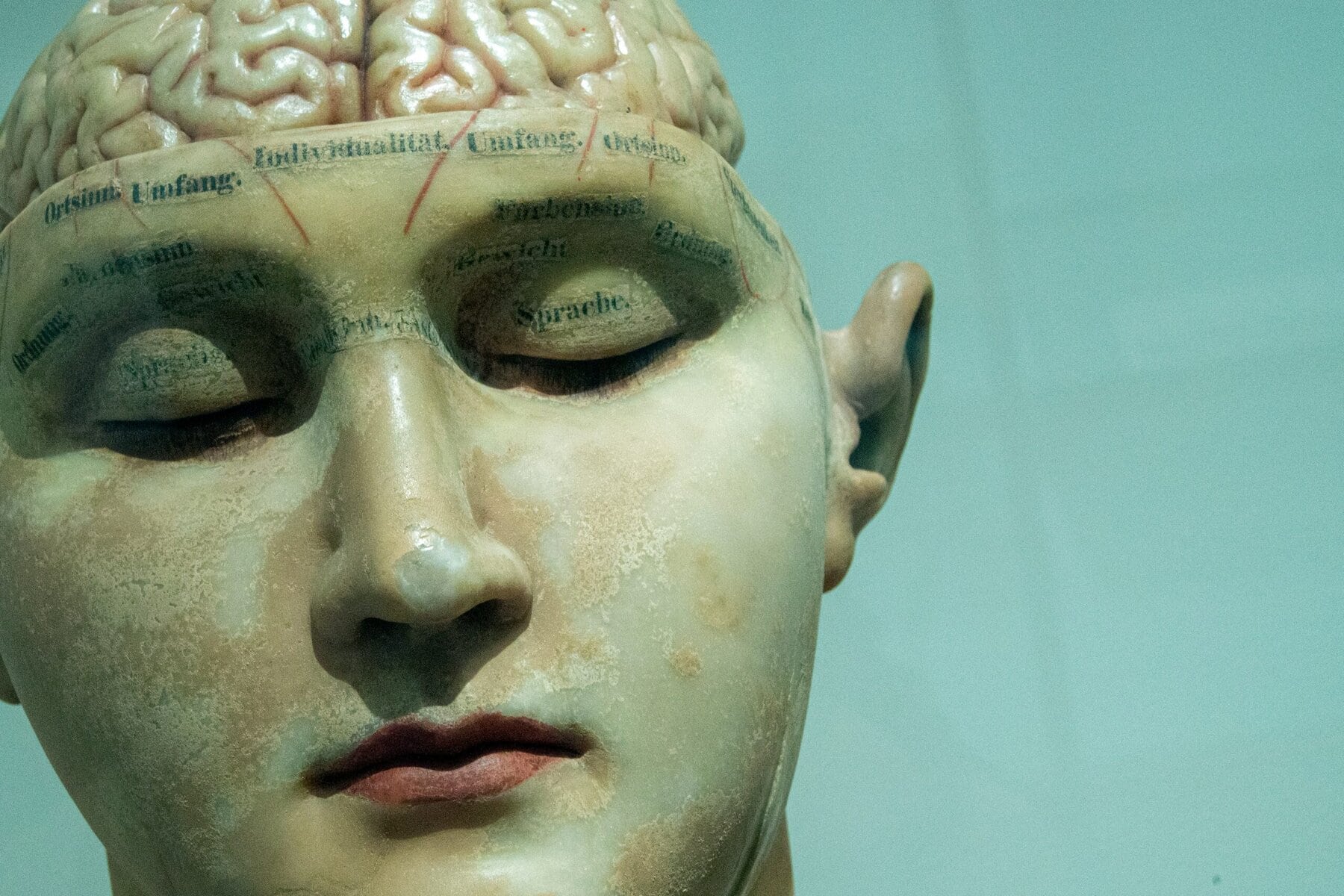

What most sets us apart from other species is our brain. Bird, mouse, whale, chimp and human brains are similar in their basic architecture and cell types.

Partly, it’s a numbers game: humans have more nerve cells and many more complex inter-neuronal connections.

But that isn’t the whole story — whales and elephants possess twice the number of nerve cells in their brains, compared to humans, yet show no signs of competing with human intelligence.

What’s sets the human brain apart from those of other highly intelligent species is the extent to which our brain is lateralized and specialized compared to other species.

In humans, the two cerebral hemispheres play very different but complementary roles for cognitive powers, language, emotion and processing sensory information.

Dominance of one hemisphere for control of the speech, forearm and hand and eye are well known features of this specialization and lateralization. Those lateralized differences between the cerebral hemispheres, which are so much a feature of human brains are either absent or minor features in our living primate relatives.

So, yet another indication of exceptionalism for humans.

But what really sets humans apart on the exceptional scale is our collective intelligence and ability to pass on our knowledge from generation to generation, initially by language, later by illustrations and texts and these days electronically though the web and social media have turned out to be mixed blessings.

Unfortunately, for all our cleverness, and growing control over nature, humans have failed to develop equivalent wisdom.

Our history suggests that too often we resort to solving disputes between differing cultures, beliefs and nations by force and these days, given the power of modern weapon systems, that’s a very dangerous path to take.

In short, exceptional as we are in technical matters, we have yet to develop the collective wisdom and will needed to share the resources of the planet for the welfare of others and the planet: witness the inaction on climate change despite alarming changes in just the last 10 years.

To return to the question — are we exceptional? Yes, but we have become far more dangerous than at any time in the past — armed to the teeth and often resorting to violence by preference.

Does anyone think the turmoil in the Middle East will ever end? Any pauses seem to last long enough for warring parties to catch their breath long enough to rearm for the next outbreak.

Ditto for Ukraine and bordering countries in Eastern Europe and looming threats in the Far East or even threats between ordinarily friendly neighbors. It’s never a safe time with bullies in charge and globally, there are a lot of grievance driven bullies looking for fights.

It isn’t just political bullies: other issues loom. What about gene editing without considering the consequences for other species and the ease with which novel viruses and other pathogens can be created on low budgets almost anywhere? Or what about the looming threat that artificial intelligence poses to a growing number of jobs in the future?

Lots to be concerned about and so far, no solutions.

Dr. William Brown is a professor of neurology at McMaster University and co-founder of the InfoHealth series at the Niagara-on-the-Lake Public Library.