On the evening of Sept. 3, I sat in the audience and observed the presentation made to the municipal heritage committee, which recommended voting in favour of advising council to move forward on the issuance of demolition permits allowing the Shaw to destroy two historic buildings in the Queen-Picton Heritage District.

Although this decision would, as the town’s consultant from ERA Architects clearly pointed out, negatively impact the historic fabric of the district, it could be justified based on the Shaw’s contribution to the town’s arts and tourism sectors.

Further, it was suggested that consideration should be given to the Shaw’s efforts, within its constraints, to ameliorate the impact of this proposed new behemoth of a building on Niagara-on-the-Lake’s gentle historic streetscapes.

But don’t worry about that, they continued, because there is an expectation that a commemorative plan — replete with plaques, images and so forth — would be developed to ensure we’d all recall what had been lost and serve as permanent monuments where we can mourn the desecration of our heritage district.

It was at this juncture my mind harkened back to a scene from an old western movie in which a robber baron, gesturing to six men dead on the street, said, “They were in the way of progress, so I had them removed.” Whereupon he pulled a handful of coins out of his pocket, dropped them on the ground and concluded, “That should pay for their burial and tombstones.”

In a voice laden with irony, the sheriff replied, “It’s mighty generous of you to pay for the markers that will remind their widows and children of what they had and what they’ve lost.”

Of course, in our case, the “memorials” around the misplaced, contextually inappropriate proposed leviathan will serve as a poignant advertisement to visitors that the Town of Niagara-on-the-Lake neither respects nor protects the history and character embodied in the built heritage of its streetscapes.

And it is that character which fuels the visitor (and resident) experience — something echoed by a recent visitor who was quoted in this newspaper saying, “I just really like the architecture, I think it’s a very cohesive look altogether and it’s giving a lot of small-town vibes.”

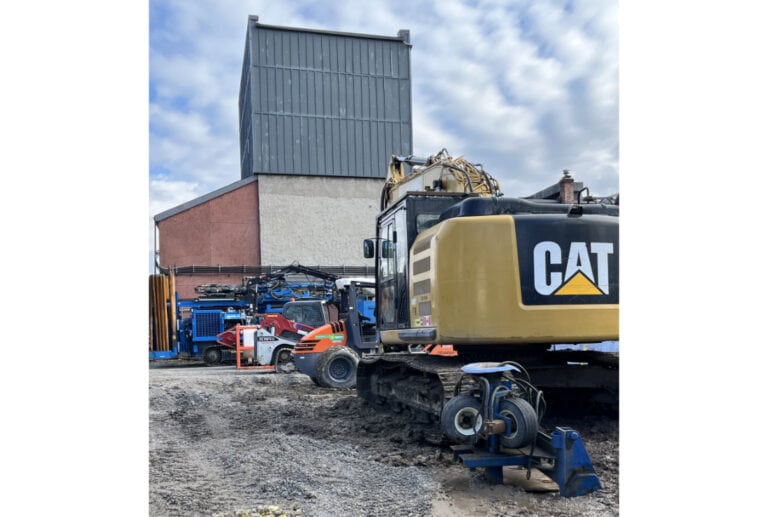

Now, while the majority of my professional colleagues feel that the correct approach for the old Royal George would be to preserve it, structurally stabilize the building, then subject the interior to adaptive reuse, perhaps within an expanded theatre, let’s simply consider the proposed redevelopment design as currently presented by the Shaw.

Beginning with the “ghost facade” proposed for Queen Street.

There are many reasons why “ghost facades” have been subject to professional criticism over the recent decades. However, in the context of Royal George, I will just focus on two — these being the lack of authenticity and mediocre to terrible execution.

Speaking to the former, far too often a ghost facade prioritizes a superficial appearance over functional reality — something the authors of the Habitable City website refer to as “lifeless masks” that lack the substance and integrity of a truly integrated building.

In the Shaw’s proposal, this lack of integration and lifelessness is further accentuated by actually creating a physical separation between the “ghost facade” and the building itself, augmented by a disassociation between the architectural styling of the building’s actual facade and the “ghost facade,” rendering it well and truly a “tombstone.”

In terms of execution, it may be beneficial to compare and contrast ERA Architects’ work on the ghost facade incorporated in 132 Yonge St. — the historic Elgin Block portion of the Bay Adelaide Centre East Tower in Toronto — with the Shaw’s proposed ghost facade.

Aside from the fact ERA’s facade actually served the purpose of contributing to an intensification of heritage fabric on the immediate streetscape and was installed as an unbroken continuation of the historic facade, they actually disassembled a portion of the heritage facade into 34 pieces, made silicon moulds of them and subsequently cast accurate reproductions which were, in turn, utilized to create a “ghost” which actually recalled the historic architecture.

In doing so, ERA managed to execute an integrated and aesthetically pleasing ghost facade, as opposed to the stranded, characterless and sad concrete monolith proposed by the Shaw.

As a final note to this week’s column, allow me to posit that the openings of a building — that is, the windows and doors — are some of the principal elements in establishing its stylistic character. Not only is the shape, size and treatment of the openings (and any decorative surrounds) key to this character, but they also serve to create a sympathetic relationship with the other buildings that comprise the streetscape.

Not even a passing nod to the streetscape has been made by the Shaw’s architects in the choice of blatantly commercial treatments of the openings. In fact, it is almost as though they deliberately decided to divorce the building from its streetscape in order to draw attention to its non-conformity — a “hey, look at me” moment.

And we’ll visit Victoria Street next week.

Brian Marshall is a NOTL realtor, author and expert consultant on architectural design, restoration and heritage.