I was privileged to attend a lecture by the eminent Canadian architect, Brian MacKay-Lyons at the Willowbank School of Restoration Arts.

For those unaware, MacKay-Lyons is the recipient of multiple awards for his work and is internationally recognized for his unique architectural expressions which he once described as being “rooted in culture, but contemporary.”

In his 2015 acceptance speech of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada’s Gold Medal, MacKay-Lyons asserted the importance of this award is “to reaffirm a way of making architecture about place — its landscape, climate and material culture” and, “because it recognizes a body of work rather than the fashion of the day.”

And, as the content of his presentation illustrated, these two tenets are central to the philosophy expressed in his own portfolio.

Generally describing architectural design geared to the fashion of the day as terrible, he blamed an education system that promulgates expression of ego over the discipline of the craft, informed by a sense of place.

He spoke of establishing an educational summer design-build program as an effort to save young architects from having “their souls swallowed by corporations” by big developers’ requirement for assembly-line mediocrity at the expense of good architectural design.

It’s telling that MacKay-Lyons, whose main body of work is unabashedly contemporary, adheres strictly to a sense of place derived from understanding its existing (or historic) vernacular materials, building culture and forms.

Consider his design of the B2 Lofts building in Lunenburg, N.S. — a superb example of a contemporary interpretation of traditional vernacular building in that “place” — which MacKay-Lyons introduced by saying, “I hate gambrel roofs but, in this place, it was the right decision.”

Moreover, I observe that not only does his body of work invariably speak to “place identity” as outlined in this column on Oct. 8, but each one and every one of his projects incorporates all of the core principles of “good” design as we defined Oct. 16.

Simply put, he is both a credit to his discipline and a creative tour de force. Would that more architects might follow his example.

Which brings us to considering an architectural design proposed for our town.

As a preface, I have made it a rule in this column not to “house-shame” an owner-occupied residential building – no matter how inappropriate or bad the architecture happens to be. However, proposed architectural plans are just lines on paper and remain subject to both criticism and owner-directed change.

Let’s take a look at a design proposed for the property at 240 Gate St., brought before the municipal heritage committee in their Oct. 1 meeting.

As background, the applicant had presented and received a permit to add two additions to this circa 1820 Georgian house in 2020.

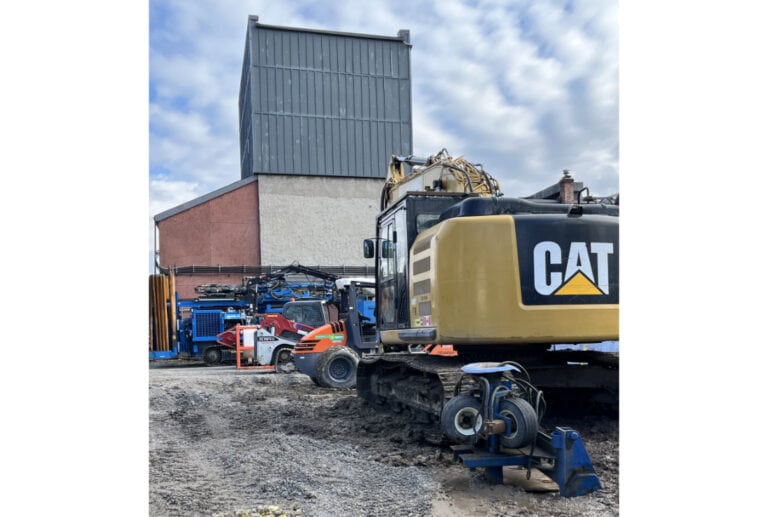

However, due to the contemplated hotel expansion on the easterly shouldering property, the owner(s) wished to revisit the permit to create a larger separation “wall” between their residential property and said expansion.

Therefore, a new design was offered to the committee, increasing the addition’s height and length.

While the owner’s desire to create separation is completely understandable, the new design should have taken this application completely off the rails.

The 1820s building has a gable roof and the 2020 permitted western (right) addition has a gambrel roof but the new design proposes adding a third roof style (mansard) on the easterly addition — adversely impacting at least six of eight core design principles. It will result in a disjointed, haphazard and cluttered street presentation.

The new design proposes a front dormer on the easterly addition, completely out of scale with the size of the addition’s contribution to the facade.

Furthermore, the full height openings (replete with the Juliette balcony element) dwarf and adversely minimize the modest openings on both the historic facade and those on the western addition while diminishing the heritage assets of the historic 1820s building.

We could go on, but suffice it to say, the new design has little that will result in a good piece of built architecture.

But, despite an alternative design offered by one qualified committee member to correct the shortcomings of the proposal, it was recommended without change.

Say what?

So, I would implore the owner to take a sober second thought vis-a-vis the design.

Right now it’s just “lines on paper” but, once built, you (and everyone else) will have to live with the building’s legacy in the neighbourhood.

Brian Marshall is a NOTL realtor, author and expert consultant on architectural design, restoration and heritage.