There is an extremely disturbing trend in this province directed at marginalizing, diminishing or outright destruction of our shared history, built heritage and cultural landscapes.

This movement appears to have been given momentum by the Ford government’s changes to weaken long-standing provincial heritage protection laws in various pieces of legislation passed during the last six years.

These changes have made it clear that Mr. Ford and his cronies believe heritage is “just so much old stuff” that belongs in the dustbin of time.

Following the provincial lead, it seems that several Ontario municipalities are cutting back on support for heritage services.

In the most egregious example, on July 9 this year, Halton Regional Council made its final decision to “cease delivering heritage services” by the end of the year and to “deaccession” — read get rid of its heritage services department while giving away or auctioning off — its collection of about 30,000 historical artifacts.

This decision has left heritage professionals “shocked,” according to Dr. Michelle Hamilton of Western University in a July 27 CBC article by Saira Peesker (“Ontario’s Halton Region shutting down heritage division, getting rid of 30,000-item historical collection“).

In July, St. Catharines city council voted against the recommendations of both their staff and the consulting firm — paid to conduct a heritage conservation district study — to create a heritage district in the city’s downtown (“Arch-i-text: The importance of heritage conservation district — analyzing our neighbours, St. Catharines,” July 31).

In a 7-4 decision, council simply reversed its 2023 pro-heritage position.

A few weeks ago in Oakville, a grand, Part IV-designated, circa 1830 Colonial home and adjacent heritage tree were razed to the ground without permission or permits.

This, in spite of the province’s maximum penalty, which could be levied upon someone convicted of demolishing a designated heritage home of $1 million and a year in prison, or both.

Did the current owner (1475 Lakeshore Road East Inc.) feel that, given the prevailing environment in the province, the risk of financial penalty — which is unlikely to hit the million-dollar mark — was worth the reward of a clean slate for future development of the property they paid $7.6 million for in 2021?

In April, in Niagara-on-the-Lake, the town was devastated to learn of a fire — which police are investigating as criminal arson — that completely destroyed Glencairn, John Hamilton’s 1832 Greek Revival home.

Adding insult to injury, there are plans afoot to sever a portion of the attached lands — which would have been highly unlikely to be approved if the building remained intact — but may now be considered due to the diminishment of the property’s heritage value under its Part IV designation.

To be clear, I am not casting any aspersions by making this observation, but simply reflecting the state of affairs as they currently exist.

In 1986, the citizens and council of Niagara-on-the-Lake came together and created the Queen-Picton heritage conservation district.

For nearly 50 years, the heritage district plan has worked to preserve and protect this irreplaceable piece of Canada’s shared history and local cultural character by ensuring that any alterations and changes are sympathetic to, and contextually appropriate within, the district’s streetscapes.

But now, five decades of careful stewardship are being threatened by the Shaw Festival’s proposed design for redevelopment of the Royal George.

The Shaw has had a long history of building in Niagara-on-the-Lake.

Beginning with the 856-seat Festival Theatre completed in 1973 and later augmented by the Donald and Elaine Triggs Production Centre in 2004 — which the architectural firm Unity Design Studio Inc. claims added “48,000 square feet of new production and administration space,” while the Shaw suggests it was 36,000 square feet, including three rehearsal halls — that was sensitively conceived to be built largely below ground to respect the design, ambience and views of the original building.

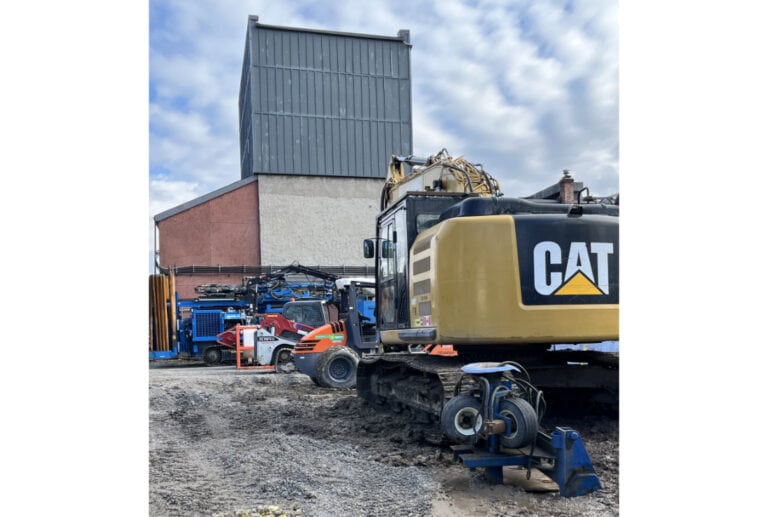

In 1980, the Shaw acquired the Royal George and has invested significant capital over the years in maintaining a failing circa-1915 building that has significant limitations from both production and accessibility perspectives. Hence, the plan for redevelopment.

As everyone knows, the first design iteration — which the Shaw claimed was preliminary and still undergoing development — was, in the main, a straight-up 20th-century commercial behemoth proposed to be shoehorned into a gentle heritage streetscape and received loud, nearly unanimous rejection by residents.

And the Shaw promised to address its issues in a revised design.

And what did we get?

A 20th-century commercial building slightly reduced in square footage with an industrial grey flytower that, on Queen Street, is marginally (but not really) disguised by a very odd, floating — not actually attached — “ghost façade” island to commemoratively recall the façade of the old Royal George.

And, on Victoria, the introduction of two gable roofs sit atop a similar commercial façade replete with a massive glass and metal bay window.

This is not a design rethink. It is tokenism — a simple pandering attempt to assuage public opinion.

I suggest Shaw’s architects visit Niagara-on-the-Lake (if they have not already done so), actually consider the existing streetscapes of the heritage district, and then develop a new exterior presentation which conforms to the guidelines of the heritage district plan.

Brian Marshall is a NOTL realtor, author and expert consultant on architectural design, restoration and heritage.