“Niagara-on-the-Fake” was a descriptor that the late Peter Stokes would acerbically apply to certain architectural designs and buildings in this town.

But, honest to goodness, if I have to hear one more person who lacks the expertise that this eminent restoration architect possessed — while simultaneously implying they know where and when Stokes would have applied the label — it is apt to make the top of my head explode.

Peter John Stokes (not “John Peter” as has been recently suggested by the Shaw’s architects) had a deep understanding of good architectural design, complemented by a profound knowledge of heritage conservation.

It was the mastery of his chosen disciplines that underwrote Peter’s condemnation of specific historical replica building designs while, at the same time, allowing him to draw the New Traditional neoclassical façade of the Royal George.

To those lacking his professional acumen, this could be interpreted as contradictory — “do as I say not as I do” — but, that is not the case.

During the second decade of the 20th century, while scholarly folks were still wrestling with its definition, Stokes was implementing how understanding “place identity” should inform design — particularly as it related to the precepts of heritage conservation in an urban setting.

In my reading, perhaps the most concise scholarly definition of place identity can be found in Harriet Wennberg’s 2015 “In Place: A Study of Building and Identity,” wherein she writes:

“In the architectural sense, place identity is the sum of specific material components and features, which provoke non-material symbolic meanings for collective groups of inhabitants and users. The existence and essential role of these material components and features mean that the generally agreed upon distinct identity of a place can be literally perceived and defined.”

A “place” may occasionally be a single building, sometimes a landscape but, most often, a cluster of buildings that comprise a streetscape which is bound together and realized as “distinctive” by material components people can easily recognize — such as shape, form, size, texture, materials, colours and details.

Moreover, there is a relationship that develops over time between those who live and associate with a distinctive “place” and the place itself – something that engenders a communal sense of belonging and purpose.

It is what Wennberg describes as, “Place identity in the built environment arises from both continuity and distinctive characteristics, and concerns the meaning and significance of places for their inhabitants and users.”

Thus we can understand why Stokes might feel comfortable designing a theatre facade after the neoclassical tradition — particularly given that its shape, form, size, texture, materials, colours and details echo and complement those distinctive components which engender Queen Street’s place identity while adding to the established relationship between people and the “place.”

While, in the case of a historical replica design — should the reproduction be so accurate as to render it virtually indistinguishable from an actual heritage build and/or if it was incongruous within an existing neighbourhood or streetscape thereby using isolation to suggest an historical building which pre-dated the surrounding buildings — he might feel completely justified labelling it fakery (a deliberate attempt to deceive).

Now, there are many, many other considerations which an architectural expert would draw upon; space constraints in this column do not allow us to outline.

So, leave us proceed by accepting that, in my opinion, Peter Stokes would be aghast by the insertion of the proposed design of the Royal George redevelopment into the Queen-Picton heritage district.

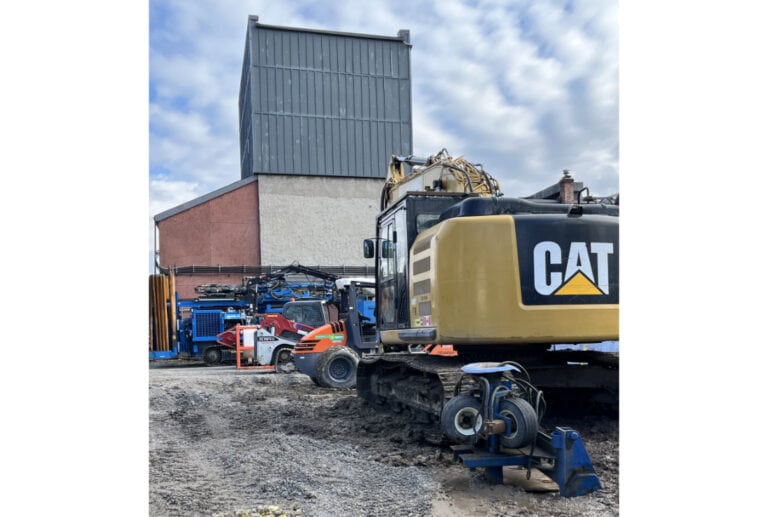

Setting aside the sacrifice through demolition of several historic buildings, in no way does the proposed design respect the “place identity” of either Queen or Victoria streets.

Imagine the Shaw Festival Theatre building, coloured concrete grey, raised to three storeys — absent the ameliorating slide roofs (which soften the festival building’s height) — inserted into the Queen/Victoria streetscapes.

Literally, this is the minimum of what is being proposed (and arguably, at 46,000 square feet above grade, the new Royal George might be larger and more imposing than the Festival Theatre).

The argument that, 50 years into the future, the “new” Royal George might be considered a part of our heritage district’s reimagined fabric is pure sophistry — predicated on completely junking the existing place identity in favour of a sadly deficient modern reinterpretation.

Bluntly, people, should this overture go forward, the heritage district you know and love will be assigned to the “dustbin” of history to facilitate the Shaw’s ego project.

Ego project, you ask?

The Shaw’s past annual financial statements have reported, on average, a failure to break even from ticket sales income, with that shortfall offset by income from charitable benefactors.

So, one is forced to ask from a strictly business perspective, how can the ticket sales from a mere +/- 15 new seats offset the increased annual operating expenses associated with an additional 35,000 square feet?

The short answer is, subject to correction from a fully supported business plan, this overture is a white elephant completely dependent on charitable donations.

In other words, an ego project.

We are being asked to accept the partial destruction of the Queen-Picton heritage district’s place identity on the very questionable altar of a cultural institution’s ask.

Is this reasonable or supportable?

I’d think not.

Brian Marshall is a NOTL realtor, author and expert consultant on architectural design, restoration and heritage.