It often amazes me how, once a concept is adopted by the government, the actual success of the concept is rarely – if ever – quantitatively evaluated.

It seems to be an axiom amongst those involved in public service, whether elected or employed, that once a core premise in policy direction is established, it becomes sacrosanct and duly engraved in stone.

To illustrate this, let’s explore a 20th-century concept that, by nearly every metric, is patently false but still a core premise in government.

Loosely stated, this concept can be expressed as: “Bigger is better and can be achieved through centralization.”

Corporations went down this conceptual road as well. However, over a period of time, a curious trend became evident in corporate books: it seemed that the more employees your company had, the less productive each employee was.

This observation was confirmed in studies conducted by analytics guru, Allan Engelhardt (Cybaea Limited) from which he concluded, “…when you triple the number of employees, you halve their productivity. Or: When you add 10 per cent employees, the productivity of each (employee) drops by 6.3 per cent.”

Now, for a corporation willing to accept lower margins on higher volumes, this scenario still can yield growth in total profits. However, what happens in the public sector – where there are no “profit” benefits – when these same parameters are applied?

Consider Ontario’s public health care sector which, in the last four decades or so, has undergone drastic restructuring.

In 1975, there was a network of small local hospitals across the province that handled the bulk of standard service provision. When a particular case, or cases, exceeded their capabilities, it was transferred to a larger facility with the equipment and specialists to be addressed.

Fast-forward to today and the vast majority of these local hospitals have been closed in favour of large complex health care centres that intake all persons requiring medical services.

If we posit a small, local hospital with a front-line health care employee complement of 200 people as representing a maximum employee productivity comparator and we apply Englehardt’s productivity loss calculation to a hospital with a front-line employee population of 800, our per-employee productivity has dropped by 61 per cent.

In straightforward terms, for every 10 cases handled by a single front-line health care employee in that small local hospital, the big fancy complex health care centre can only handle 3.9 cases per single front-line employee.

And the maximum number of cases per employee only gets worse as the health care complex’s total employee complement increases.

This loss of employee productivity is not due to lowered individual effort. On the contrary, each employee of a large organization may be working “harder” than their small organization counterpart.

Most experts who have studied the productivity question suggest the issue lies in communication. In brief, the more employees an organization has, the larger a cadre of middle management is required, in turn leading to a more complex reporting and administrative system.

This complexity not only increases the time spent by individual employees on non-service delivery tasks but also lengthens the decision-making timelines. Moreover, legacy systems that no longer serve any practical purpose are rarely, if ever, discontinued: non-productive “paperwork.”

Is it any wonder that the quality of our health care system has significantly declined over the last four decades while the cost of the system has ballooned?

Bigger and centralized is certainly not better … but it is more costly to the taxpayer.

Let’s stay on this thread while turning our attention to another bigger and centralized is better overture once again being floated by the provincial government – amalgamation.

I seem to recall hearing the Ford government’s rationale for considering amalgamation before: It was back in 1996 when then-premier Mike Harris announced that the amalgamation of the six lower-tier governments comprising Metropolitan Toronto would save up to $645 million after amalgamation and $300 million annually thereafter.

The consulting firm KPMG produced a report that estimated the cost of this amalgamation at no more than $220 million.

So, how did that work out?

Well, the total cost of amalgamation was actually 20 per cent higher than estimated, landing at $275 million. The predicted $645 million disappeared like a puff of smoke, but they did manage to report an annual savings of $135 million.

However, those “savings” (due principally to the elimination of elected officials) were almost immediately eaten up and surpassed by the expansion of the municipal staff and associated budgets necessary to navigate the much more complex government organization required to service the new City of Toronto.

In reality, and where the rubber hits the road, the total operating cost budgets for 1997 (the last year before amalgamation) of Metropolitan Toronto totalled $4.59 billion.

The following year (in constant 1997 dollars), that cost jumped by 18 per cent to $5.6 billion and, by 2008 (again in constant 1997 dollars), the total had reached just shy of $8.1 billion – roughly a 70 per cent increase.

This is no surprise to scholars who have studied “amalgamation” undertakings around the world. Quite simply, in the vast (nearly all) majority of cases examined in these studies, academics have found that amalgamation does not reduce costs — it increases them.

Even after Premier Doug Ford slashed the size of Toronto council, according to the city’s published budget summary, the financial shortfall – read deficit – as of Dec. 31, 2023, is $1.64 billion.

That money will need to come from taxpayer pockets (property tax increases, etc.) or add to federal/provincial deficit borrowing, increasing the generational debt our government has bequeathed upon our children and grandchildren.

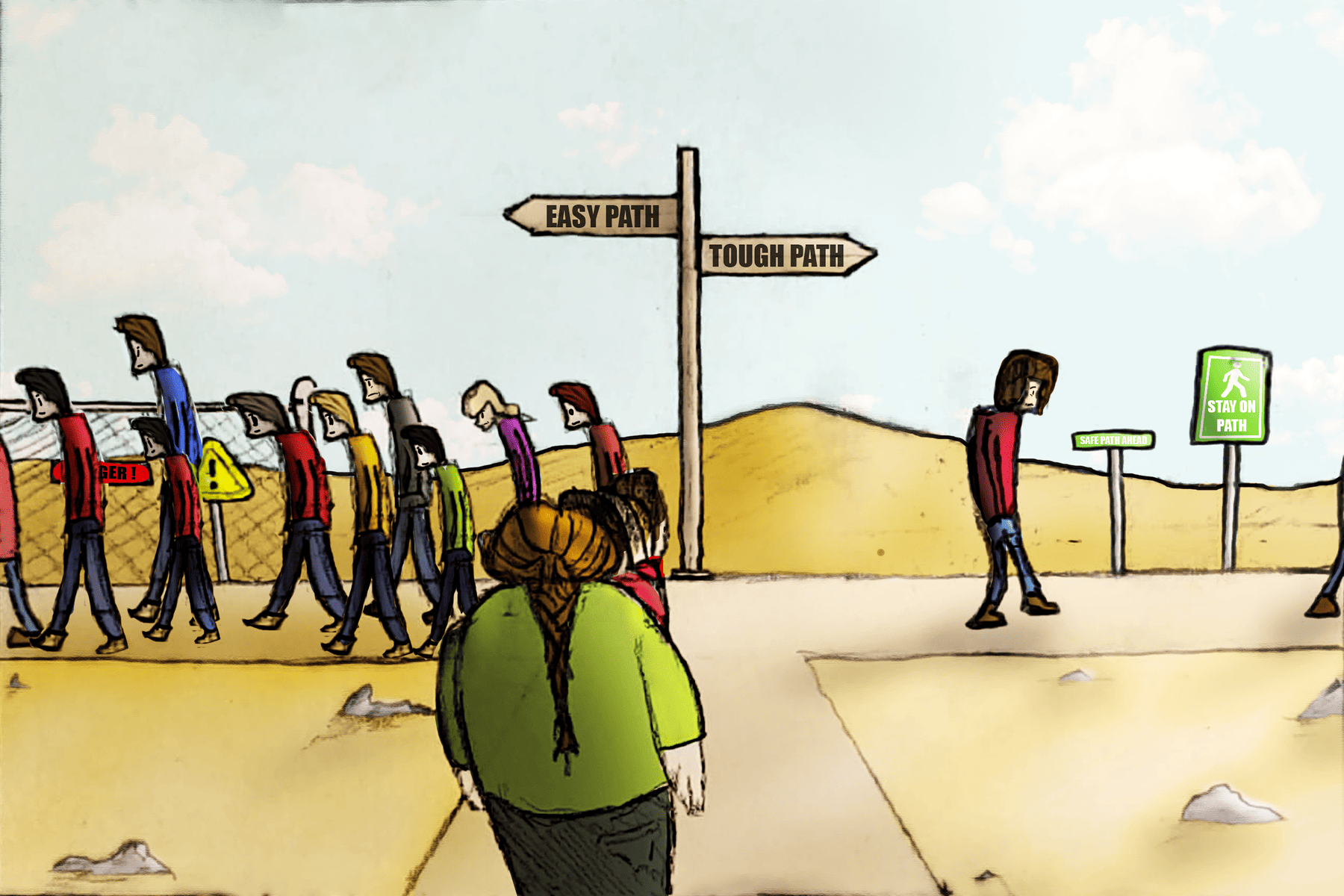

Even a very cursory consideration of the facts presented in this column leads one to ask the question: why would an elected politician, at any level of government, support embarking on a path that has no service delivery benefits while increasing costs exponentially?

Oddly, some of the politicians suggest that amalgamation will allow for a total overhaul of the administrative systems that expedite housing development approvals — get more homes built faster.

However, even if this overhaul were done (and done well), I’d suggest it would take more than a decade with a cost well into the billions of dollars — which doesn’t really accomplish the stated objective regarding speeding development.

There are others who suggest that reducing the number of elected officials will not only save money but also speed decision-making.

Our lord mayor recently observed that the total salary of Niagara-on-the-Lake’s town councillors is only $182,000. It’s my observation that council costs us less than one upper-middle-level bureaucrat.

Further, I’ve noticed no appreciable increase in the speed of decision-making since Ford reduced Toronto’s council from 47 to 25 in 2018, but I have noted an increase in staff positions.

Bigger is not better … it not only increases financial costs (tax burden) but also lowers individual productivity while reducing the representation of the taxpayers in the processes of governance.

There is a redolent smell of coffee in the room … For goodness sake Ford, take a deep breath and wake up.

Brian Marshall is a NOTL realtor, author and expert consultant on architectural design, restoration and heritage.