Penny-Lynn Cookson

Special to Niagara Now/The Lake Report

It’s spring and what a pleasure it is to be on the grass in Ryerson Park sharing with others the splendid views of the lake, nesting birds, sailboats and barges.

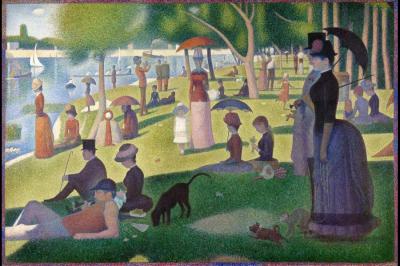

Late 19th-century Parisians enjoyed similar Arcadian delights by spending Sundays on a small island in the Seine, La Grande Jatte, where they strolled, fished, went boating and took their children. It became the subject for the most significant painting of Neo-Impressionism created by its founder, the French artist Georges Seurat.

An art prodigy, Seurat studied the classic traditions of line and colour at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris but he sought a new formula of optical painting inspired by reading aesthetic and scientific treatises on colour harmonies.

He achieved this by applying small comma strokes and dots of unmixed colour side by side on the canvas rather than by mixing the colours on the palette. The effect was a more intense luminosity. He called this “divisionism” but we now know it as “pointillism,” named for the dots.

Seurat was against the Impressionist technique of instinctive and spontaneous capture of fugitive light and colour. He favoured restraint, optical rules and deliberate rigid stylization, not as a loss of freedom but rather an objective means to a greater reality through structure, line and composition.

Seurat spent every morning for months on La Grande Jatte drawing studies of people and the landscape. Afternoons were spent in his studio integrating the studies with live models holding the positions. The result was a large canvas, 7 x 10 feet, exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in 1886 and described by critics as cause for “mental disturbances” and “choking apoplexies.”

Seurat’s masterpiece and his methods were hailed by young artists, the avant-garde and Impressionists, such as Pissarro and Signac, who altered their styles.

What made this painting so different? The figures appear wooden in frontal, back or profile positions with exceptions being a bounding small dog in the foreground and a running girl in the middle ground.

It is a study of the bourgeoisie, the middle class, enjoying the pleasures only available to the aristocracy before the French Revolution. They are well-dressed except for the sprawling man smoking his pipe in the left foreground. There are repetitive curves in the top of the dandy’s cane, dog tails, umbrellas and the bustle of the woman’s skirt in the right foreground.

Shadow, light, reflections and colour are brilliantly executed. Perspective pulls the eye into radiance and depth. Details abound from a monkey on a leash, to the horn-playing musician, to various types of river boats, a woman fishing, and to each cast shadow, leaf and blade of grass. It is a work of mind over eye and a triumph.

Seurat died suddenly at 31. He had found his classical style early, a product of his inquiring explorations and the scientific optimism and positivism of the time. His powerful legacy as the leader of the Neo-Impressionists would endure for decades and influence many artists such as the Fauves, Matisse, Kandinsky and Mondrian. And all based on the dot.

Penny-Lynn Cookson is an art historian who taught at the University of Toronto for 10 years. She was also head of extension services at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Watch for her upcoming lectures at the Niagara Pumphouse Arts Centre and RiverBrink Art Museum.