Penny-Lynn Cookson

Special to Niagara Now/The Lake Report

Vincent van Gogh left the Netherlands to join his art dealer brother Theo in Paris where he would further his studies and come into contact with, and be influenced by, the discoveries and work of many of the Impressionists including Monet, Seurat and Pissarro.

However, in time, van Gogh craved a place of solitude where he could assimilate what he had learned in order to create new work under different circumstances. He wanted to leave Paris and its many distractions and get back to nature and serenity.

Although he planned to go to Marseilles, he stopped in Arles, the ancient port of the Phoenicians, which had become a military, cultural and religious centre for the Romans from 123 BC. Van Gogh was so enchanted with Arles that he decided to stay.

It was a new world for him, a world of sun, warmth, tropical beauty and the relaxation of the south so appealing to northerners. It was everything he had hoped for: vibrant colours, strong light, the Camargue plains and marshland of the Rhone delta and the picturesque appearance and customs of the local Provencal inhabitants.

In his letters to his sister and brother, van Gogh wrote glowingly, “Nature here is so extraordinarily beautiful” and “Things here have so much line and I want to get my drawing more deliberate and more exaggerated.”

He soon realized his vision had changed after a few weeks and that he saw things differently “with an eye more Japanese” (he was a collector of Japanese prints). “You understand,” he explained to his sister, “that nature in the south can’t precisely be painted with the palette of the north. A palette nowadays is absolutely colourful: sky blue, pink, orange, vermilion, strong yellow, clear green, pure wine red, purple. But by strengthening all colours, one again obtains calm and harmony …”

Van Gogh painted feverishly, canvas after canvas, drawing after drawing, 300 in one year, driven by the desire to express specific ideas by colour, simplification, emotion, sincerity and an overwhelming feeling for nature.

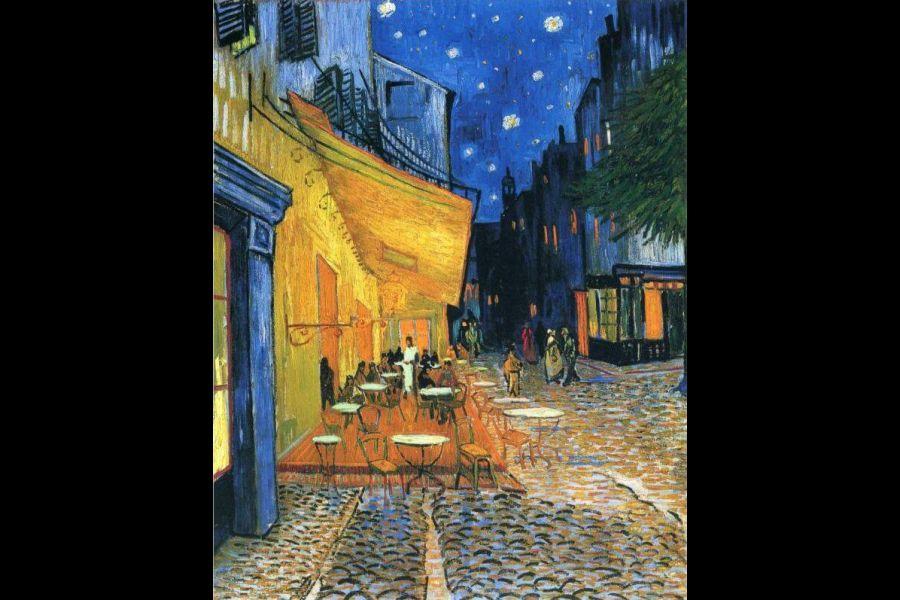

Even the most banal images were infused with dynamism. He found endless intriguing subjects and sites that appealed to him and from which he created statements of great vitality using symbolism and specific allusions with meanings both spiritual and psychological. A remarkable example of this productive period is “Café Terrace at Night.”

As we, the viewers, stroll ahead in the Place du Forum of Arles, we see under the yellow orange light of the café with its awning, 12 tables and 12 seated patrons with a white robed figure in the centre of the group.

Is he a waiter with a white apron or is he possibly an allusion to Christ and the 12 Apostles and, therefore, to the Last Supper? This man, with long black hair, stands before a window with wood strips separating the panes of glass, forming a cross behind his head.

To the left, a black-clad figure mysteriously leaves the terrace going inside. Judas? To the right, a stroller turns to observe the café scene and two couples in the shadows stand and chat. One is red robed. Mary? Our eyes are pulled into the dark Rue du Palais where an alert horse, ears forward, is drawing a carriage with a top-hatted driver toward us.

One can almost hear the clip-clop sound on the cobblestones.The awning and the diagonals of the buildings with the luminescent candle glow of their interiors lead up to the deep blue nocturnal sky full of shimmering stars and constellations reputed to be accurate to Sept. 17 and 18, 1888.

This work, created on site by van Gogh with candles stuck in the headband of his hat, is one of the three famous “Starry Night” paintings done within a year.

Although van Gogh was a deeply religious man he had turned away from the pursuit of theology to be an artist. And yet, he wrote to his brother Theo, in reference to this painting, that he felt “a tremendous need for, shall I say the word, for religion …”

As we welcome the coming days of Passover and Easter and aspire to join friends and family once again on outdoor evening terraces, we might well look up and, if it is a clear, starry night, be reminded of the extraordinary vision of van Gogh.

Penny-Lynn Cookson is an art historian who taught at the University of Toronto for 10 years. She also was head of extension services at the Art Gallery of Ontario. See her lecture series “Art and Revolution, From Cave Art to the Future” Thursdays on Zoom until April 29 at RiverBrink Art Museum in Queenston.