Penny-Lynn Cookson

Special to Niagara Now/The Lake Report

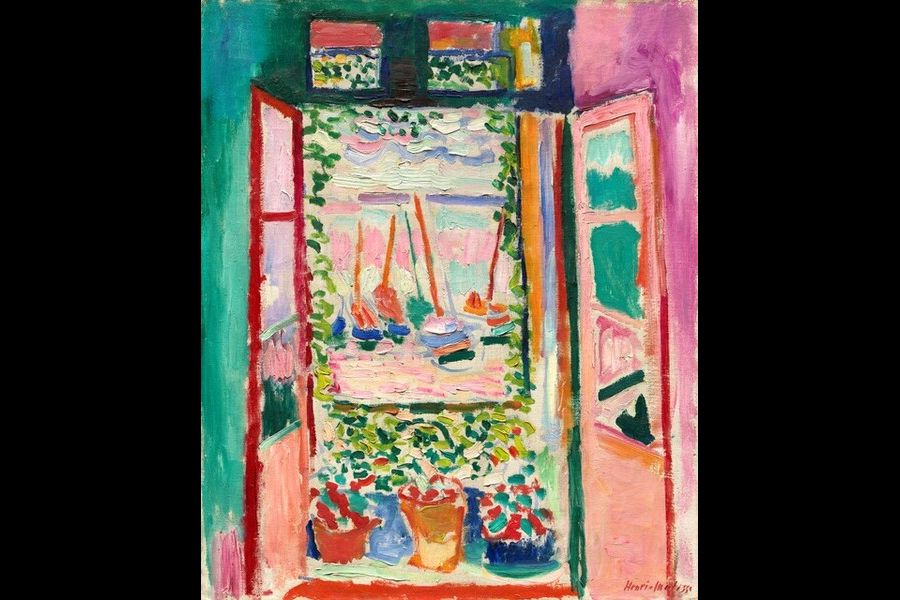

We’re opening windows to spring and flowers and blossoming trees, just as Matisse wants us to do with him in his dazzling “Open Window, Collioure.”

It’s 1905 and Matisse has left Paris with fellow artist Andre Derain to soak up the sun, sea, palm trees and warm breezes of the Cote d’Azur.

He sits in his hotel room, doors open into the interior, picks up his brushes and creates a work that communicates the positive aspects of life, spontaneity and his own joie de vivre. In this painting, he button-holes us saying: “You have to be here and see this with me!”

Matisse goes to the max, using colour right out of the tubes. He disregards chiaroscuro, light and shadow, to contrast instead broad areas of green and red, the complementary opposites on the colour wheel.

The contrast also appears in the terracotta pots on the wrought-iron balcony with their red flowers, surrounding green foliage and the red awning seen through smaller window panes. We look out to the red masts of serenely bobbing sailboats, the masts casting pink reflections in the sea.

He uses a dazzling variety of brushstrokes from long broad sweeps on the interior walls to the short, staccato dots and lines of the exterior. Each area from the interior to the balcony to the harbour has a different handling of the brushes, resulting in an effect of dancing cross-rhythms.

The composition is a series of frames within frames; the wall holding the window, the window framing the exterior, the balcony containing the sailboats, sea and sky. Masterful.

“Open Window” was exhibited at the Salon d’automne of 1905 with works by Derain and other artists such as Dufy, de Vlaminck and Braque. Although they were influenced by Post-Impressionists such as Van Gogh, Gauguin and Seurat, they now moved beyond their values of representation to emphasize strong colour, dissonance and urgent bold brushwork.

The paintings of Matisse and the others were not well-received by critics or public. One art critic, Louis Vauxcelle, wrote that a sculpture in the room was surrounded by “les fauves” (the wild beasts). The name stuck and the movement became known as Fauvism. It lasted as a style from 1904-1910 although the group only remained cohesive from 1904-1907.

Fauvism was the first avant-garde movement of the 20th century. For Matisse, the greatest of modernists, intense colour was independent, it was liberating, a means to establish structure, to unify, to describe light and space, to project a mood and communicate the artist’s emotional state.

There is no anxiety, fear, alienation or conflict in his work. In “Open Window” we share his spiritual, joyous and optimistic response to nature and life, just as he intended.

Penny-Lynn Cookson is an art historian who taught at the University of Toronto for 10 years. She also was head of extension services at the Art Gallery of Ontario. See her lecture series “Art and Revolution, From Cave Art to the Future” Thursdays on Zoom until April 29 at RiverBrink Art Museum in Queenston.