Penny-Lynn Cookson

Special to Niagara Now/The Lake Report

In this on-going year of COVID-19, when we are isolated at home and not seeing family and friends, it has become for some, a time of self-reflection, writing in diaries, reading, or putting old family photos in albums.

Ah yes, we think, there are the grandparents and great-grandparents lost to the Spanish Flu in 1918-19. A pity we didn’t know them.

There has been a curious resurgence of interest in that pandemic, perhaps because it too was transmitted person-to-person and was global with an estimated 50 million deaths, more than died in the First World War.

Artists were not immune to the Spanish Flu but surprisingly few chose to depict it as a subject. An exception was Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944), best known for his famous “Scream” paintings and prints.

Munch was no stranger to illness as a child. His mother and favourite sister had both died of tuberculosis and his physician father, who was obsessively religious, saw death as God’s divine punishment. Munch later wrote “angels of fear, sorrow and death stood by my side since the day I was born.”

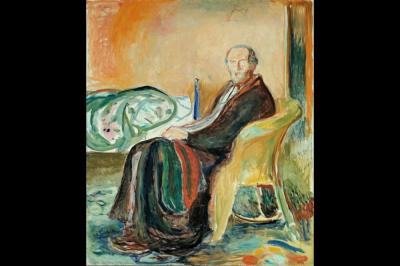

In Munch’s “Self-Portrait with Spanish Flu” (1919), he gives us a vivid view of his illness, conveying not only his physical struggle but his emotional and psychological state of mind. We see only the essentials: the turmoil of the bedcovers having been pulled up with chills and thrown back from fever and perspiration.

Munch sits in his robe in a wicker chair, fists clutching the blanket over his closely held legs and feet as he controls his trembling. He turns his face toward us. It is pale, gaunt, unshaven, his eyes are glassy and barely discernible, his gaping mouth gasps for air as he struggles to breathe.

The background is minimal, the wall bare, the hallucinatory orange and green colours deliberately strong to convey strong emotion. Detail of the room are as blurred to him as to us. The brushstrokes are loose. The work conveys fear, anxiety, tension and emotion.

He felt, and was, lucky to have survived. Munch wrote: “In my art I try to explain life and its meaning to myself” and in so doing, he gives us further pause to consider our own lives in these turbulent times.

Penny-Lynn Cookson is an art historian who taught at the University of Toronto for 10 years. She also was head of extension services at the Art Gallery of Ontario. See her upcoming lecture series “Art and Revolution, From Cave Art to the Future Thursdays” on Zoom, March 11 to April 29 at RiverBrink Art Museum in Queenston.