There is an unspoken but generally accepted assumption among most Canadians that housing is a commodity traded on the open market with the objective of generating profit.

This consideration of housing as an investment that will yield financial returns (whether or not you actually live in it) has created a speculation-driven marketplace.

In early 2023, Statistics Canada published compiled statistics looking at investor-owned properties – an investor, in this case, is defined as an owner who owns at least one property that is not their principal residence.

What it reported was that in Ontario, 20.2 percent of all properties were owned by investors in 2020. And, when considering only condominiums, that number jumped to 41.9 per cent.

Further, an article published in Better Dwelling on July 25, 2022 reported:

“Most of Ontario’s recently built condo apartments were bought by non-occupying owners. There were 58,100 units built since 2016 with known ownership, and 59.8 per cent had non-occupying owners in 2020. Ontario’s recent condo building boom only saw two in five units bought by end users.”

The report continued: “The trend applied to cities of all sizes, even small and secondary markets. Small cities like Woodstock, one of the fastest growing for price, saw 100 per cent of its 225 new condos bought by non-occupying owners.”

“London saw over four in five (82 per cent) of its 1,360 recently built condos suffer a similar fate. Investors in the much larger Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo region owned 81 percent of the 3,210 condo units recently built.”

While many of these units are rented out by their investor owners to full-time tenants, a significant number of these investment property units have been placed into the short-term rental market.

I suggest that some may count the latter as adding to the “housing supply” but they cannot be considered “dwellings.”

Moreover, the sheer volume of speculative investors looking to add units to their portfolio creates a competitive supply and demand real estate market, which drives real estate acquisition prices – and subsequent carrying costs – higher, in turn resulting in escalating rents for tenants.

Another phenomenon spawned by this “investment marketplace” assumption has been the development of large, multiple investor-financed “landlords” such as real estate investment trusts.

These investment trusts commonly promise – and deliver – high annualized returns to their shareholders.

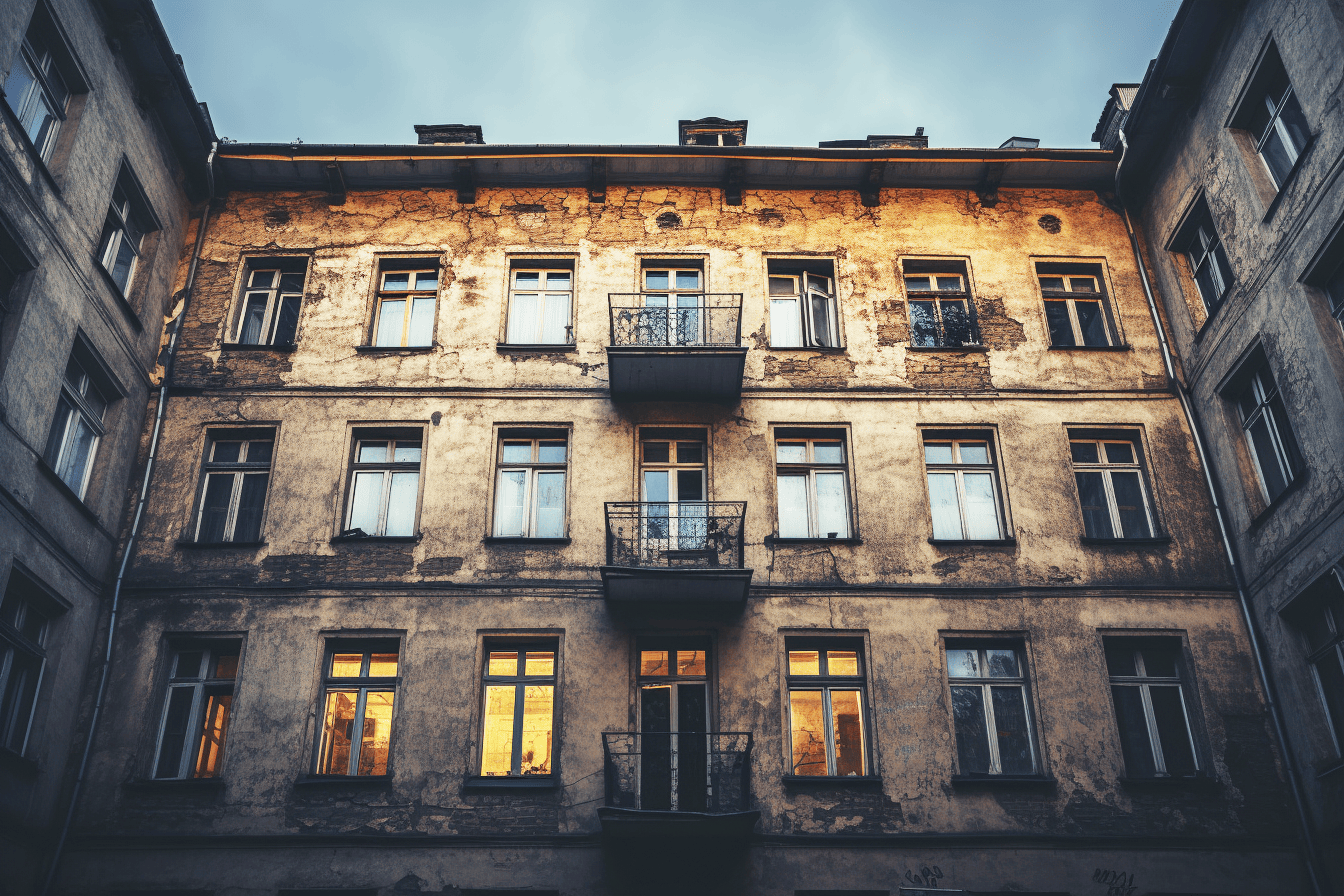

One way these organizations accomplish such high returns is through the canny acquisition of apartment buildings (or purpose-built rental complexes) in neighbourhoods on the cusp of gentrification.

They renovate these buildings – generally displacing long-term, often lower-income, tenants in the process – and subsequently rent out the “gentrified” units to higher-income households that can afford to pay going market rental rates.

So, while dwelling units are not removed from the housing stock, the units can no longer be considered “affordable.”

This depends, of course, on who is defining the meaning of “affordable.”

Both the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Statistics Canada define this term – as applied to housing – as a ratio of cost to income, specifically mortgage-carrying cost or rent, being less than 30 per cent of a household’s total before-tax income.

Statistics Canada also uses this formula to calculate the number of households in “core housing need” (households that pay more than 30 per cent) and additionally uses the same data in a slightly different formula (shelter-cost-to-income ratio) to define housing affordability (the proportion of total household income that is spent on shelter costs).

StatsCan reported that in 2021 – the most recent year on their web platform with data available – 5,968,550 Canadians lived in unaffordable housing and 2,682,765 Canadians fell into the category of “population in core housing need.”

Note that 63 per cent of those in core housing need happen to be renters and, as a proportion of the total tenant population, 27 per cent (more than one in four) live in unaffordable housing.

Now, while to myself and most other folks I speak with, this definition of “affordability” is the most financially logical and embracive, there is a second market-based definition that is used to underwrite both private development overtures, some federal programs and most provincial policies.

This second definition, rather than basing “affordable” in accordance with the householder’s ability to pay, suggests that housing is affordable if it is priced at a discounted level of full market rates.

In Ontario, the Doug Ford government used this market-based definition to define “affordable” housing as any offering priced at 80 per cent of current market rates.

Applying this criterion to the real world, a detached single-family home in a development which might be market-priced at $1 million is classed as affordable at $800,000.

Similarly, if the market price for apartment rental happens to be $2,000 per month, then according to this definition, $1600 would be affordable.

Let’s consider that $1,600 per month equals $19,200 annually and if we apply StatsCan’s shelter-cost-to-income ratio, that government agency would state that it is unaffordable for any household income below $64,000 per year.

I’d argue that, given a $64,000 gross income in Ontario equates to roughly $45,750 net take-home pay, shelling out 42 per cent of your net income on rent would be tightly living paycheque-to-paycheque, particularly if that rent did not include utilities.

However, provincial governments, many federal government agencies and developers insist on the continuance of the market-based definition as their “golden standard.”

Witness this fact when, in November of 2021, the City of Toronto amended their official plan to redefine the assessment criteria of affordable rental and owned housing in accordance with the definition utilized by Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Statistics Canada, developers appealed to the Ontario Land Tribunal the amendment bylaw within five weeks.

To my knowledge, there has been no decision rendered on this appeal to date, but Ford’s Bill 23 (More Homes Built Faster Act) did legislatively gut Toronto’s plan for affordable units in new residential projects, lowering the percentage down to a mere five per cent from 22 per cent.

Bluntly, relying on private developers to build enough truly “affordable” housing (under our first definition) to fully meet the needs of the people of Canada is a complete pipe dream.

That said, I would be one of the last people to ask a corporation to broadly sacrifice their shareholders’ return on investment upon the altar of public service.

Such an undertaking by a Canadian corporation would be contrary to its corporate fiduciary responsibilities under law.

A real, viable and lasting solution to our housing conundrum will require a complete rethink of public/private partnership collaborations, with the public side providing land, goals, criteria and oversight, while the private side supplies the focus, logistics and expertise to get it done on time and budget.

And, here in Ontario, the sadly deficient Landlord Tenant Act and the associated administrative bodies, which subject both landlords and tenants to inexcusable challenges and financial burdens, must be completely restructured.

Stay with me, folks!

Next week, we’ll explore the inequities of Ontario’s Landlord Tenant Act, an example of a Canadian city that has successfully rethought its affordable housing program and consider a few forward-moving options for Ontario.

Brian Marshall is a NOTL realtor, author and expert consultant on architectural design, restoration and heritage.