Regular readers of this column and those of you who may have attended my talks, lectures or walking tours may have noticed a tendency for me to refer to the Niagara-on-the-Lake streetscapes as “gentle.”

While this adjective is commonly applied to a landscape — referring to one characterized by mild, soft, and soothing features, lacking harshness or abruptness — it is rarely used in association with streetscapes.

Why? The answer is fairly straightforward.

As streetscapes evolve, not only do the uses of the existing buildings change, but they are modified, altered and, all too often, demolished to be replaced with new structures that are incongruous with both the rhythm of the streetscape and out of context with the surrounding buildings.

Moreover, in old downtown commercial areas, these new structures tend to “eat” into the adjacent historic residential neighbourhoods, visually overshadowing them and creating severe transitions between commercial and residential properties.

In turn, this often leads to the devaluation of surrounding traditional residential properties — unless one is a confirmed urbanite, few want to live next to or back onto a multi-storey brick or concrete wall — thus causing the exodus of single-family owners out of the area, which results in a general deterioration of the downtown area.

This is a pattern which has been repeated again and again across North America.

In fact, I would argue that the unmanaged evolution of the old commercial cores in our towns is one of the principal factors responsible for the growth of suburbia and the hollowing out of traditional main streets.

Malls and big-box stores are not the cause of the problem; they are simply a reflection of decades upon decades of failed or absent urban design oversight.

Somewhat miraculously, due largely to the strict preservation of the Queen-Picton heritage district and long-term strict adherence to by-laws controlling both new and infill development, Niagara-on-the-Lake has avoided the fate of most Canadian towns.

However, it must be observed that during the recent past, this has and is changing.

Rezoning of properties to permit the expansion of commercial development opportunities, site-specific exemptions to bylaws, and minor variances on properties are becoming the rule rather than the exception.

All without urban design oversight — you may recall that the current council deep-sixed that committee.

Which brings us back to the Shaw’s Royal George redevelopment proposal.

This column has visited the issues of its proposed massing, sheer size, out-of-context commercial design, and “ghost” façade, so we won’t beat that drum again (“Arch-i-text: The Shaw’s Royal George 2.0 misses the mark,” Sept. 11).

Instead, let’s turn to the Victoria streetscape, which currently enjoys a gentle transition from the low, two-storey Bank of Montreal building on Queen to the historic residential building form of 188 Victoria followed by the gabled and dormered garage attached by a breezeway to the Gothic Revival styled home at 178 Victoria, the Dutch colonial revival house at 164 Victoria and the Georgian on the corner of Victoria & Prideaux.

The opposite side of the street is similarly punctuated by traditional residential houses, none over two storeys.

With only one exception, these buildings are clad in clapboard, producing a pleasing continuity of materiality on the street’s various building forms.

The Shaw proposes to demolish the buildings at 178 and 188 Victoria and replace them with a blatantly commercial style street façade that includes a side gabled barn-like projection — taller than the bank building — clad in masonry and metal consistent with the rest of the facade and replete with a bank of tall ribbon windows.

Now, some attempt has been made to soften the starkness of the modern windows by introducing a linear wood decorative element over the top quarter, but this in no way mitigates the severe lines and presentation of the proposed building’s design.

In short, the Shaw wishes to tear down two contextually appropriate, compatible residential heritage buildings and replace them with a jarringly unsympathetic, massive and out-of-context modern façade, which will completely disrupt the historic streetscape(s) while eating into the residential neighbourhood and visually encroaching on the neighbours.

This is exactly the type of development proposal described earlier in this article.

Bluntly, the solutions here are many and varied — all a matter of sympathetic architectural design with delicate treatment of form, massing, scale and materiality, focused on blending in versus standing out.

And, for those who are assuaged by the suggestion that this building will be a one-off and zoned so that it can only ever be used as a theatre, think again. A future change in zoning simply requires an application passed by council.

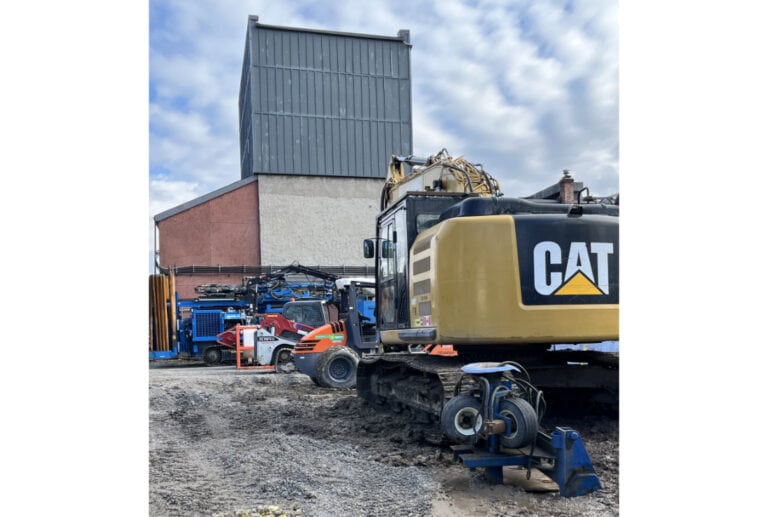

Speaking of developments granted a change in zoning to proceed, what is going on with the excavation work being performed on the Parliament Oak site?

As far as I am aware (echoed by correspondence received from many concerned residents), the hydrological study, peer review of the application documentation, etc., on this site have not been completed or, if completed, have not been published as per council direction.

Why are town staff permitting this work to move ahead?

It’s either go or no go — to my knowledge, provincial legislation has no provisions for wink-and-nod half measures.

Brian Marshall is a NOTL realtor, author and expert consultant on architectural design, restoration and heritage.