This is a work of art – yes, it is, in spite of its creator, Norman Rockwell, being dismissively referred to as an “illustrator” by art critics and curators.

“Freedom from Want” has never ceased to resonate with the North American public since the day it graced the March 6, 1943, cover of the Saturday Evening Post.

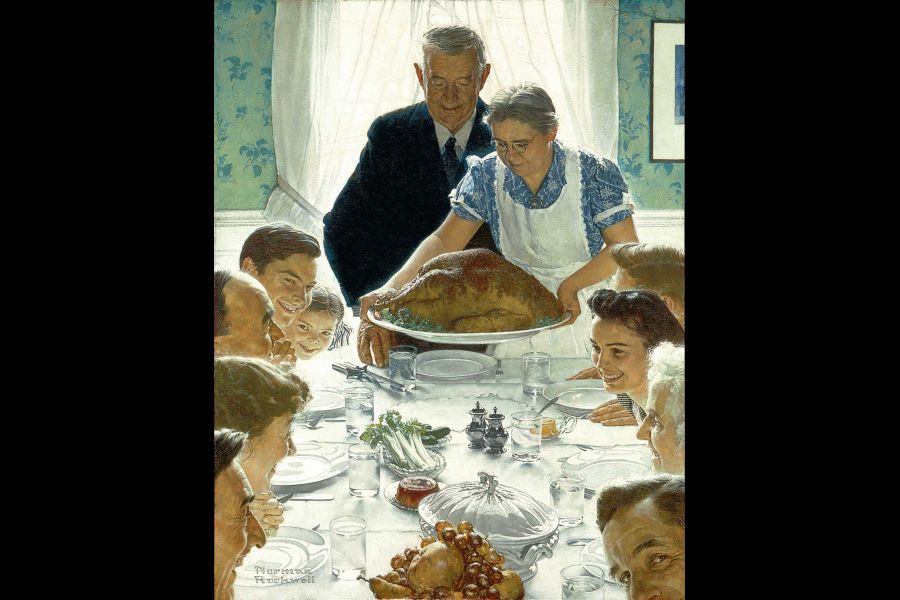

It is a happy work because it represents family, not necessarily next of kin, but friends as well, relishing shared stories, laughter and engagement with one another.

It is Thanksgiving in America. The hardships of the 1930s are over. There is no “want” in the United States because there is still abundance and gratitude in the land. The glistening turkey is being presented by the family cook but the three generations gathered at the table are not yet eyeing the bird – they are delighting in the company of one another.

It’s not about the food, although the table presents the side dishes of the 1940s: the covered casserole, likely holding hot mashed potatoes, the full gravy boat, a mould of cranberry sauce, celery sticks, a platter of fresh fruit and glasses of water. It’s a time without mobile phone fixation, cable TV background noise, short attention spans, pandemics, opioid and fentanyl concerns, and what wine goes best with turkey and won’t be destroyed by the cranberries.

Technically, the work scores high in Rockwell’s masterful handling of the white-on-white of the table, the composition pyramid of the patriarch, matriarch and turkey, and the dynamic pull of the viewer into the feast by the direct eye contact of the of the cheery male figure in the lower right.

Our eyes easily meet his before sliding left to the fruit in the foreground, which echoes the shape and colour of the turkey and, by capturing our attention, draws us back, up and into the composition.

Rockwell had a voracious appetite for authenticity of detail and although he declared, “I do ordinary people in everyday situations … and that’s about all I do,” it was American life at its best that he wanted to convey: “Santa down the chimney, lovely kids adoring their kindly grandpa sort of thing.” In so doing, he was no slouch in his knowledge and technical understanding of old masters such as Tintoretto, Hals and Rembrandt.

Rockwell always wanted to be an artist. Born in New York City in 1894, he studied at the Art Students League, then became an artist and editor for Boys’ Life, published by the Boy Scouts of America. In 1916, he had his first cover of what would be 323 original covers for the Saturday Evening Post, with its large weekly circulation of 3 million.

Inspired by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union address to Congress, which advocated four basic human rights – freedom of speech, freedom from want, freedom of religion and freedom from fear – Rockwell went to Washington to present his sketches for posters of these freedoms based on his hometown experiences in Arlington, Vt.

He was turned down by the Ordnance Department of the U.S. Army but not by the editor of the Saturday Evening Post, who commissioned the idea for four consecutive monthly covers of the magazine beginning in February 1943. The paintings were a huge success.

In a joint campaign between the Post and the U.S. Department of the Treasury the paintings went on a national tour visited by more than one million people, who purchased $133 million of war bonds and stamps. Rockwell had gone from being a national name to an American institution.

By the 1960s, America had changed. Rockwell‘s focus and work of the next 10 years for Look magazine turned to civil rights, race, ethnicity and poverty, most memorably seen in two multiracial paintings, “The Golden Rule” which includes the phrase “Do Unto Others as You Would Have Them Do Unto You,” and “The Problem We All Live With” in which Ruby Bridges, a small Black girl in a white dress, is being escorted by four federal marshals to integrate a school in New Orleans.

Rockwell said, “I really believed that the war against Hitler would bring the Four Freedoms to everyone. But I couldn’t paint that today. I just don’t believe it.” He had outlived his subject matter.

But his public still wanted the old comfortable Rockwell world shielded from the uncertainties of violence, doubt and fear. His work may not be collected by the major museums of the world or found in the annals of the history of art, but in the history of mass communication and America’s popular image of itself, Rockwell’s impact has been profound and recognized.

Hollywood film directors such as Spielberg and Lucas and illustrators of posters, albums and books continue to be influenced by his work. He painted the portraits of four presidents: Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon.

In 1977, a year before he died, Rockwell was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, his nation’s highest civilian honour. The Norman Rockwell Museum, located near his home in Stockbridge, Mass., includes not only his paintings, drawings and studies, but is a national research institute dedicated to American illustration art.

Penny-Lynn Cookson is an art historian who taught at the University of Toronto for 10 years. She was also head of extension services at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Watch for her upcoming virtual lecture series “Concepts of Beauty: Artists, Models, Muses” for the Niagara Pumphouse Arts Centre in January 2022.