In both world wars, there were men killed in action or who died in service who had a connection with Niagara-on-the-Lake but for various reasons were not commemorated on either the memorial clock tower cenotaph in Old Town or the Niagara Township war memorial in Queenston. In some cases, they lived for only a brief time in Niagara and had no family here when the monuments were built. In other instances, they had lived near McNab, not then part of NOTL or Niagara Township. While their names are not read out at the ceremonies at these monuments on Remembrance Day, they too should be remembered.

__________________

In St. Andrew’s Cemetery stands a tombstone marking the final resting place of George David Wright, who was only three days old when he died on Sept. 18, 1906.

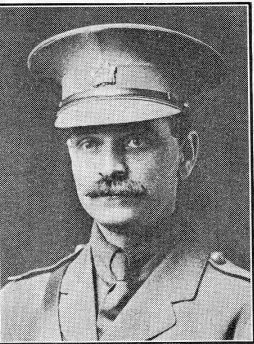

He was the son of William Jonathan Wright, the principal of the Niagara-on-the-Lake high school, and his wife Mary Robertson.

William Wright was the youngest son of George and Emma Wright.

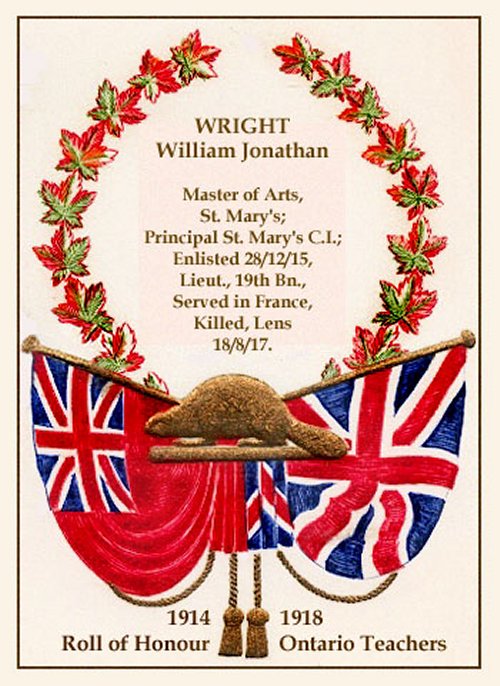

Born Nov. 14, 1874, in Oxford County, William attended school in St. Marys, Ont., and received a good education, earning a master’s degree at the University of Toronto in 1897. He became a teacher.

On Christmas Day, 1902, William married teacher Mary Edith Robertson in the bride’s hometown in Cold Springs, in Northumberland County.

The couple’s first child was Dorothy Helen, born in 1904 in Cold Springs, where William was teaching. Emma had quit teaching after her marriage.

The following year the young family moved to Niagara-on-the-Lake, where William served as the principal of the high school, now part of the Niagara-on-the-Lake Museum.

In 1906, they suffered the loss of baby George and two years later had another son, born in Niagara-on-the-Lake, William Robertson Wright.

They did not stay long in Niagara, with William transferring to the high school in Forest, Ont., in 1908. Their second daughter, Margery Emma, was born there in 1910.

In 1913, the family moved again, when William became principal of St. Marys Collegiate. He also served as a part-time militia officer in the 28th Perth Battalion.

Patriotism was the stated reason for William deciding to volunteer for active service in the First World War.

He was 41 years old with three young children at home. Nobody would have thought ill of him if he had remained a teacher at home serving in the local militia.

Nonetheless, he volunteered for service in 110th Overseas Battalion on May 5, 1916, and was confirmed in his rank as a lieutenant.

Three months later he sailed to England, arriving in Liverpool on Aug. 30, 1916. One of the men who served with him testified that: “No man ever answered the call of King and country with a purer motive. “

While overseas, William and Mary wrote to each other continuously, with Mary reporting local happenings. William wrote of his experiences, in and out of the front-line trenches.

William expressed his feelings on the war: “There are a dozen worse things than death. Disgrace, shame, guilt, dishonour, lack of patriotism are all worse. Liberty and free government cannot be won and kept without sacrifice. I am glad to be able to do anything to end this awful war.”

In May 1917, Lieutenant Wright was transferred to the 4th Trench Mortar Battery.

The move gave Wright a break from front-line duty in June and early July while his unit underwent more training. He returned to the front line in July when the Canadians were preparing for a major attack on German positions on Hill 70 near Lens in France.

On Aug. 26, 1917, fighting in a series of Canadian attacks and German counter-attacks, fate found Lieutenant Wright. He was killed outright when a German squad overran his mortar position.

Wright was buried at the Fosse No. 10 Cemetery in Sains-en-Gohelle, France.

On May 15, 1919, Mary wrote to NOTL historian and museum curator Janet Carnochan thanking her for sending an article about William published by the Niagara Historical Society.

She spoke of her “blues” and loneliness, and that her depression deepened as the soldiers who had survived the war were sailing back to Canada. William’s 19th Battalion would be welcomed in Toronto by cheering crowds, reunited with their loved ones.

Mary opened her heart and expressed her feelings about the return of her husband’s battalion from overseas.

“I am afraid I shall have another collapse when I read of its arrival and reception in Toronto. How different everything would have been for us had he been coming and what a different person I would have been!”

Tens of thousands of wives, parents, siblings and friends of the fallen would have understood.

Today the lonely tombstone of baby George is the most visible reminder of this branch of the Wright family in Niagara-on-the-Lake.

Lt. William Wright’s name is not included on the cenotaph on Queen Street in Niagara-on-the-Lake.

- On the heels of The Lake Report’s 53-part “Monuments Men” series, which exhaustively documented the story of every soldier commemorated on the town’s two cenotaphs, Ron Dale’s “Missing in Action” stories profile Niagara-on-the-Lake soldiers who died in wartime but are not listed on the town’s monuments.