How big a health risk do pesticide sprays pose in Niagara-on-the-Lake? It depends on a few key factors — and, maybe, who you ask.

While some in Ontario, such as the Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks, maintain that pesticides, when used properly, are safe, others are concerned about the potential risks, including a phenomenon called spray drift, which one public health expert flagged to NOTL’s council — with a mixed response.

The Government of Canada defines pesticide spray drift as what happens when a pesticide stays in the air long enough to drift off the area it’s being sprayed and onto other areas by accident.

Donald Cole is a public health medicine consultant and professor emeritus at the University of Toronto. He describes pesticide spray drift as “the aerial movement and unintentional deposit of pesticide outside the target area.”

He said studies from Canada, the United States and Europe have found that people living near vineyards and orchards can be exposed to pesticide residues.

“Drift depends on many things, like weather conditions and the type of spray equipment being used. Because spray drifts downwind from the place being treated, the farther away you are from the area being sprayed, the less drift there is,” the government states on its website.

There are two types of pesticide drift, Cole said: particle drift and vapour drift.

Particle drift happens when spray droplets or dust move beyond the area being treated. Vapour drift occurs when pesticides evaporate and move as invisible gases, sometimes long after spraying.

Cole was invited by Ed Werner of Brox Company Limited to address these concerns in front of NOTL council during the town’s committee of the whole planning meeting in September.

Werner is in a legal dispute with Konzelmann Winery and the town over planning and enforcement.

He asked Cole to outline potential health risks from pesticide drift while discussing conflicts between farming operations and nearby residents.

He told council the studies he references show people living near vineyards and orchards can experience pesticide spray drift, though he said there are no studies on vineyard guests.

“What are the potential health effects of exposure to pesticides? There are immediate poisoning (such as) headaches, skin rashes, breathing problems. Skin rashes were particularly noted among children in a school next to a spraying operation in vineyards in France,” he added.

His presentation warned that other potential health risks of exposure to pesticides also include birth defects, spontaneous abortions and different types of cancer.

That’s when Coun. Erwin Wiens asked to stop the clock: “We’re dealing with a site-specific plan here and this is a planning study. I’m trying to understand the correlation.”

Wiens, also a local farmer, questioned Cole’s remarks, as he brought no evidence of improper spraying or harm in town.

“To make that allegation that that’s going to happen — it just wasn’t right. It wasn’t fair. It was meant to further a personal agenda as opposed to using proper science,” he said in an interview.

As housing, business and tourism expand into agricultural areas, Cole said farmers now carry more responsibility to keep bystanders safe.

Wiens said farmers are licensed and trained to use pesticides safely and complaints are looked into when reported: “We want to make sure we investigate that.”

In Ontario, only “appropriately trained individuals,” including certified farmers, can use commercial pesticides, said the ministry in an email.

It said pesticide drift is not a concern when products are used according to federal label directions — a requirement for certified farmers.

Label precautions include: requiring the use of certain types of equipment, spraying only at certain times of the day, specifying the amount that may be used for a given area and establishing untreated areas, called buffer zones, to protect nearby areas, said the ministry.

Other label requirements include avoiding spray-drift-causing weather conditions and spraying near others.

Wiens argued there is no need for concern if rules are followed. He noted his own farm borders a school and said he has never sprayed during class hours.

“I would never do that. We go out at night,” he said.

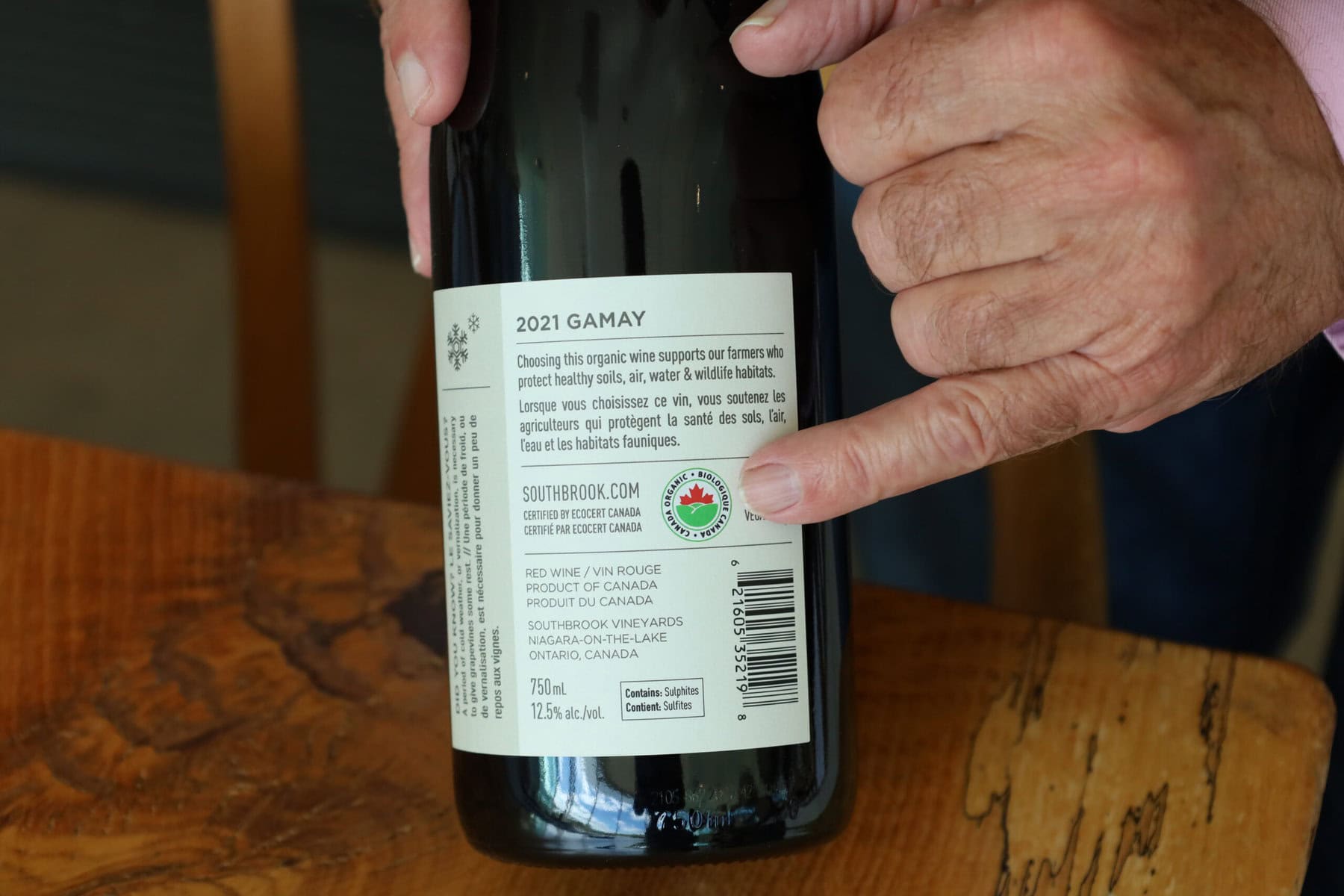

At Southbrook Winery, proprietor Bill Redelmeier says he’s taking no chances.

He says he stopped using agricultural chemicals two decades ago out of concern for his workers.

“I didn’t think it was right for me to ask my workers to do something that I wasn’t willing to do,” he said.

Southbrook, which became Canada’s first winery certified both organic and biodynamic in 2008, has built its philosophy around sustainable viticulture and “light-on-the-land” winemaking, principles Redelmeier said reflect his commitment to quality, worker safety and the environment.

“What we’re using is way less toxic than the conventional,” he said, acknowledging organic methods are not risk-free, but pose “way less of a concern.”

Wiens argued the difference is overstated.

“Whether it’s organic or conventional, they are all restricted pesticides that have to be applied with a licence,” he said. “The risk still exists.”

Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency approves or denies pesticide use, assessing health and environmental risks from spray drift before allowing use, the ministry said.

Regardless of the type, pesticides are essential for keeping crops alive, said Wiens.

“I don’t know of anywhere where they’re not using pesticides in the globe,” he said, adding sprays prevent rot, mildew and leaf curl — which can devastate orchards.

Wiens said conventional fruit looks cleaner and shows less rot than organic fruit, but added that Southbrook is “filling a niche.”

Redelmeier, who focuses on quality over price, said the trade-off is worth it — accepting lower yields and less uniform fruit to prioritize quality and safer working conditions.

“If we stop competing on price, then we can start making big changes,” Redelmeier said.

How often vineyards are sprayed depends on pest pressure, grape variety and weather, with most applications from late spring through summer.

The ministry encourages farmers to manage pests in smarter ways — such as preventative pruning and regular monitoring — so they can spray less.

Using prevention-first methods not only helps to reduce drift, Cole said, it “can also reduce farm production costs, benefitting the farm operation and reducing exposure to pesticides.”

Modern equipment, safer sprays, waiting the proper time before farmers return, keeping a safe distance between crops and guests and avoiding windy or unstable weather also reduce risk, he said.

The general public should “recognize and adopt a precautionary approach to toxics use in their own activities,” Cole added.

Although legally not required, “the ministry encourages growers to communicate with their neighbours regarding the use of pesticides, such as voluntarily notifying adjacent properties of the application,” it said.

If residents suspect pesticide spray drift exposure, they can report it to the ministry through its public reporting hotline or Spills Action Centre toll-free, 24/7 at 1-866-MOE-TIPS (1-866-663-8477) or 1-800-268-6060. Or, online at report-pollution.ene.gov.on.ca/.

Or, Health Canada at canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/about-pesticides/are-pesticides-safe.