This is the first in a four-part series based on a talk given as a part of the Niagara Historical Society’s lecture series. Because of the pandemic, the series, “All along the Waterfront” was done via Zoom. All of the talks are available online through the Niagara-on-the-Lake Museum.

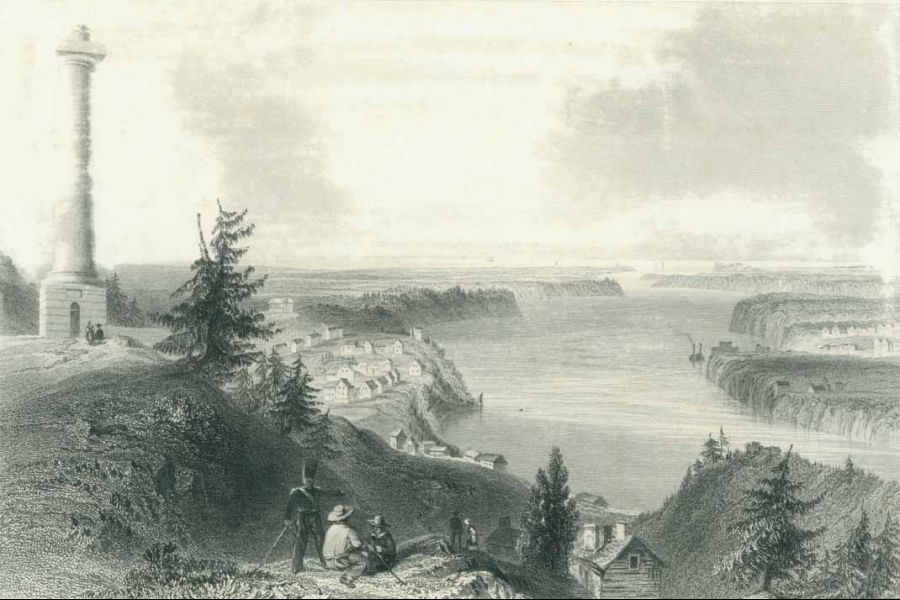

There is much of historical significance in Queenston.

It survived the War of 1812, and was home to several well-known people: Laura Secord, Robert Hamilton and William Lyon Mackenzie, among them. Rather than concentrate on people, I am focusing on the village’s relationship to the Niagara River.

To begin at the beginning, it’s necessary to know why Queenston exists.

Local geography comes into play. The Roy Terrace on the Ontario side of the Niagara River and the Eldridge Terrace, which is just across the river in New York state, mark the height of what was Lake Iroquois during the time that glaciers covered North America.

Lake Iroquois eventually became Lake Ontario. When the glacier receded about 12,000 years ago, Niagara Falls was born here, where Queenston and its sister village Lewiston sit today. The water fell 11 metres over the escarpment from a small Lake Erie into Lake Iroquois.

At the time, the lake plain from Queenston to Niagara-on-the-Lake was covered with the waters of Lake Iroquois. The height of the lake was the same 11 metres, the height of the Niagara escarpment.

The site of the birth of Niagara Falls was discovered by a geologist named Dr. Roy Spencer and today this site is known as Roy Terrace.

Indigenous peoples were the first to inhabit the area. By the time Europeans arrived, the Neutral Confederacy, a political and cultural union of Iroquoian nations who lived in the Niagara area, used the river and its shores for hunting and fishing. They also cultivated crops of corn, beans and squash as well as tobacco.

The earliest European on record to acknowledge Niagara Falls was Rene Brehant de Gallinee, who saw them in 1669.

Later came Father Louis Hennepin, a Franciscan priest, who accompanied Rene Robert Cavelier, Sieur de LaSalle’s team of explorers in 1678. Hennepin wrote extensively of his travels. The RiverBrink Art Museum library in Queenston has a collection of his letters.

Moving into the 18th century, the European colonists wanted to open the interior to the fur trade and to the military. They wanted forts and trading posts.

Since the only efficient transportation method was by water, the real issue became how to get around the falls.

They needed a portage.

The portaging of goods has been described as the second-oldest economic activity in North America, trade being first.

The Niagara River was the main route for the transfer of military supplies and fur trading items. Along with the return shipments of furs, portaging became the chief economic activity of the area.

The original portage was on the east, or American, side of the river. It was shorter than the Canadian route -– about 13 kilometres s versus nearly 18 kilometres. Queenston and Lewiston both were bustling ports.

And then came 1775. The American Revolution changed Queenston’s fortunes. By 1790 it was clear that the Canadian portage was the only one open to the British.

Enter Robert Hamilton. Born in Scotland in 1753, Hamilton was a merchant and politician. By 1780, he was living in Upper Canada and had formed a partnership with Richard Cartwright to supply goods to the British army at Fort Niagara. Around 1784, he settled in Queenston.

After the American Revolution, Lord Dorchester, the governor general of British North America, asked for tenders to open a portage road. Robert Hamilton was one of the two applicants.

Hamilton had been using the Canadian portage route since 1788 and had hired settlers to provide the necessary oxen and wagons. These settlers wanted to continue with what was regular work and pay. They petitioned the government in favour of Hamilton, who won the contract.

The portage road ran from Queenston to Chippawa. Hamilton built small storehouses in both villages.

Meanwhile, the British military built a wharf, guardhouses, blockhouses and two-storey storehouses at Queenston, Chippawa and Fort Erie. The military and Hamilton’s staff worked together on these projects.

Next: Queenston was a busy inland port.