Penny-Lynn Cookson

Special to Niagara Now/The Lake Report

In February 2020, I was in Paris to see the Leonardo da Vinci exhibition at the Louvre. The museum was open late during the final days to accommodate the crowds, so for three rainy nights I walked alone along dark streets back to my hotel.

It was eerie. Buses, streets and bars were empty, no one was out except an occasional dog walker. Was it due to a virus story coming out of Wuhan? One night I stopped, transfixed by the bright interior of a corner café with four people: a couple dining late, a single man fingering his wineglass, and a bored waiter gazing out to the street.

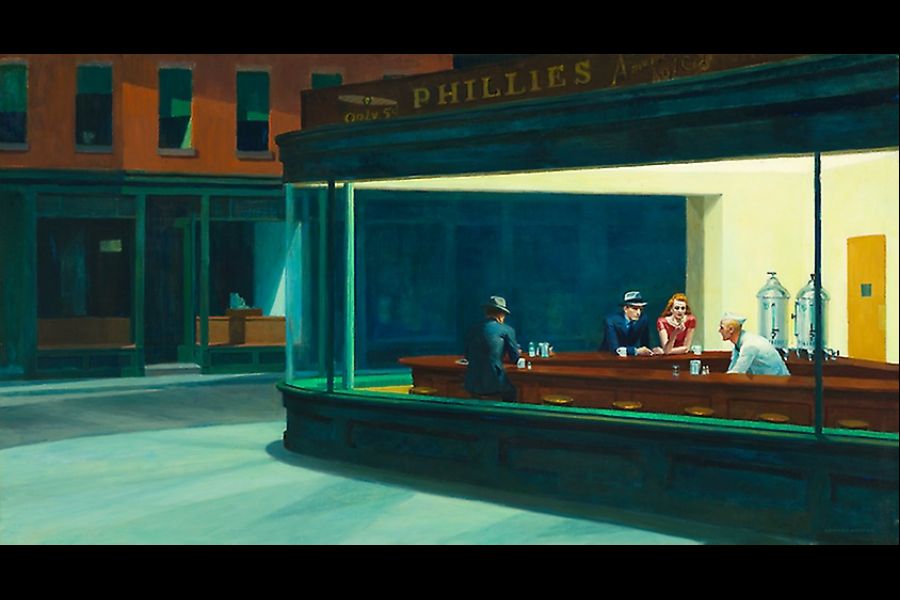

It was Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks,” painted 78 years earlier in New York City, transferred to Paris. This is what Hopper’s paintings do. Once seen, they tenaciously lodge in your mind. You don’t forget them.

They are quiet, spare, melancholy, mysterious. They speak to solitude, our isolated states, being alone although not necessarily lonely. They resonate. They make you think.

Edward Hopper is considered to be the greatest American realist artist of the 20th century. At a time of anxiety in America, Hopper began painting “Nighthawks.” The Japanese had bombed the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

Hopper did not create spur of the moment. Each canvas took a long time of solitary thought, planning and studies. But when he was ready, his interpretations of intimate American life were symbolically suggestive, dramatic and powerful. They are not narratives but reveal everyday life in familiar settings: apartments, houses, offices, cafés, on the road.

In “Nighthawks,” a few people are having a coffee in a diner, late at night. Although they are connected by the counter, the figures are detached, lost in their own thoughts. The woman examines something in her right hand, her other hand almost touches the man’s hand holding a cigarette, suggesting intimacy.

We see only the angled back of the single man and the light catching his cheek. The bending server looks out toward the street, perhaps seeing himself in the glass. Hopper’s handling of light and shadow is masterful in the sharp contrast of the fluorescent-lit interior of the diner and the dark exterior, as well as in the detailed nuances of shading on the men’s suits and fedoras, and the woman’s skin, hair and dress.

Colour is saturated, establishing mood. The composition’s long diagonals are intersected by short verticals supporting large pane glass windows and the prow curve where there would normally be a door. The diner is topped by an ad for Phillies, America’s No.1 cigar, for 5 cents.

In the closed office building across the street, Hopper indicates human presence even when there is absence. The windows, like eyes, have green roller blinds pulled down at different heights and on the ground floor the cash register in the empty room waits for the cashier. An unseen streetlamp casts light and shadow within these silent enclosed spaces.

Hopper continues to have an enduring influence on artists, poets, filmmakers and now memes online, with the Simpsons, Star Trek, Batman and Superman and even Banksy at the “Nighthawks” diner.

Penny-Lynn Cookson is an art historian who taught at the University of Toronto for 10 years. She also was head of extension services at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Watch for her upcoming lecture series at the Pumphouse Arts Centre and at RiverBrink Art Museum.