When workers defraud their employers, it typically is because they are desperate and in dire financial straits, says a NOTL forensic accounting expert.

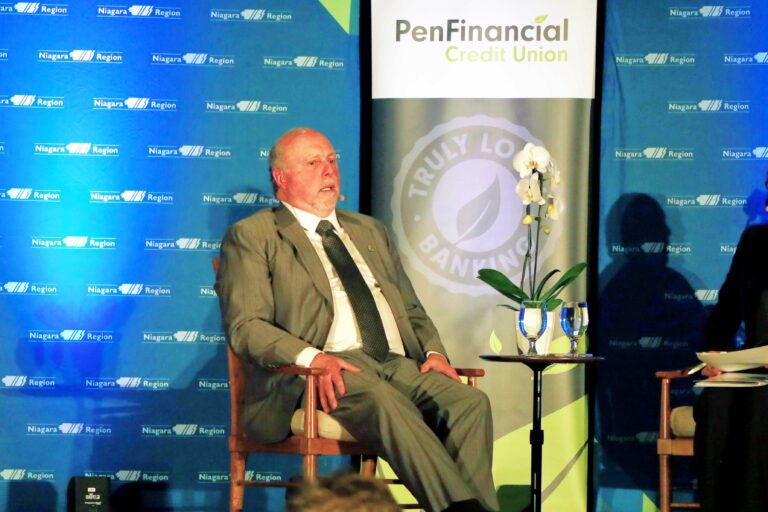

Having large debts or gambling and drug addictions are some of the common factors that can lead people to commit fraud, says Oleh Hrycko, a retired forensic accounting expert.

Hrycko was the founder of one of the largest independent forensic accounting and computer forensics/e-discovery firms in Canada.

While he has no involvement in or knowledge about the Niagara-on-the-Lake Hydro fraud case, in more than 30 years of investigating a wide variety of cases, the NOTL resident has really seen it all.

“They usually start off small, say $500, to see if it works, and maybe months later, 'Let's try $1,000,' and then they go to many thousands and they come up to a point where they feel, it's under the radar. And then they simply keep doing it,” Hrycko said in an interview.

“There are three common elements that explain an individual’s motivation to commit fraud – opportunity, incentive and rationalization,” said Hrycko. In the fraud investigation business, investigators like Hrycko look for “red flags.”

Vendor payable fraud often involves false supplier invoices, inflated billings or duplicate invoices from a supplier, he said.

“In false invoice schemes, what typically happens is the perpetrator will first set up a corporation that they control. Using readily available software, they will then generate fictitious invoices from their corporation, which will be below a certain dollar threshold so as to avoid scrutiny,” he said.

“Since these individuals also usually have the authority to pay vendor invoices up to a certain dollar amount, they will process these fictitious invoices through the organization for payment to their fictitious corporation”, Hrycko said.

“There's a whole bunch of red flags on these fictitious invoices. You could have vague or incomplete invoices with blank fields, you can have typos and you can have invoices without any supporting documentation, like purchase orders and receiving reports. ” he said.

The fraud is often caught by another staff member.

“In many of the cases that I have investigated in the past people go on vacation” and a colleague filling in for them uncovers something questionable.

Likewise, if someone seldom takes a vacation, it could be a red flag. “If they haven't taken a vacation for two years, you know this thing's been going on for two years because that person is afraid to take vacation” for fear of getting caught.

Spot audits can also catch problems, he said. “Let's just say there's widgets being ordered using fictitious invoices. And they start trying to locate those widgets in inventory and they find out that the quantities don't even exist” – that's another red flag.

“If you have the proper protocols in place at the organization, you greatly mitigate the potential for a false invoice fraud,” he said.

“Segregation of duties” is one of the fundamental controls in an organization for minimizing fraud, he added. That means, for instance, someone who is responsible for processing the accounts payable invoices for payment should not be the final authority on paying those invoices.

“If someone's in charge of vendor payables and then that person is also in charge of issuing payments to those vendors, this creates one of the common elements to motivate an individual to commit fraud – opportunity,” Hrycko said.

“If that person has an approval limit up to $5,000 unlikely anyone is going to check payments that are less than $5,000 to a particular company because that falls within the organization’s procedures,” he said.

It might get caught in a year-end audit, but depending on what controls are in place, such fraud cases can go on for years without being noticed, he said.

Investigators like Hrycko are equal parts detective and accountant, and they love the work. “It was always a hunt for me,” he said.

In addition to his forensic accounting firm, in 2001, he started another firm specializing in e-discovery and computer forensics investigations. This firm was involved in many major “electronic investigations” including the Air Canada corporate espionage lawsuit against WestJet that was settled in 2006. WestJet admitted accessing commercially sensitive information about its rival by using a former Air Canada employee's password.

With the digital data trail we all create now, investigating fraud and corruption can be easier than following old-school paper trails. And people's work computers can be a trove of information.

Today when an organization uncovers a suspected internal fraud and identifies a perpetrator, in addition to gathering the paper evidence, the investigative protocol also involves preserving the perpetrator’s computer laptop/desktop along with “CDs or USB keys or external hard drives.”

“Once you get into the computer, unless they reformat the hard drive or use professional wiping software, or simply destroy it using a sledgehammer, we always told our clients, delete doesn’t mean delete and we can usually find it.”

As a veteran forensic accounting investigator, Hrycko's advice to companies is straightforward.

“It starts with senior management, so there has to be a fraud risk awareness within the organization. There also have to be very strong policies and procedures in place, including the segregation of duties of critical roles within the accounting/finance area,” he said.