Ron Dale

Special to The Lake Report

During the Second World War, 13,408 men of the Royal Canadian Air Force were killed in action. Another 1,855 were reported as “missing, presumed dead.”

In most cases, the missing had crashed into the English Channel trying to return to England after their aircraft suffered heavy damage over Europe.

Many other airmen were killed when their planes were shot down over Germany. When possible, the Germans recorded the identity of those they buried.

Canadian servicemen were issued with two fibre identification discs to be worn around the neck. The tags, however, were not fireproof and any serviceman whose body had been burned could not be identified.

This was particularly the case with airmen whose planes frequently were shot down in flames.

Through the International Red Cross organization, the Germans reported to the British the identities of the dead, if possible, or the identification of the crashed plane and the names of prisoners of war.

Many airmen were able to avoid capture and eventually returned to England. In several cases, a missing man would not be presumed dead until long after he was killed.

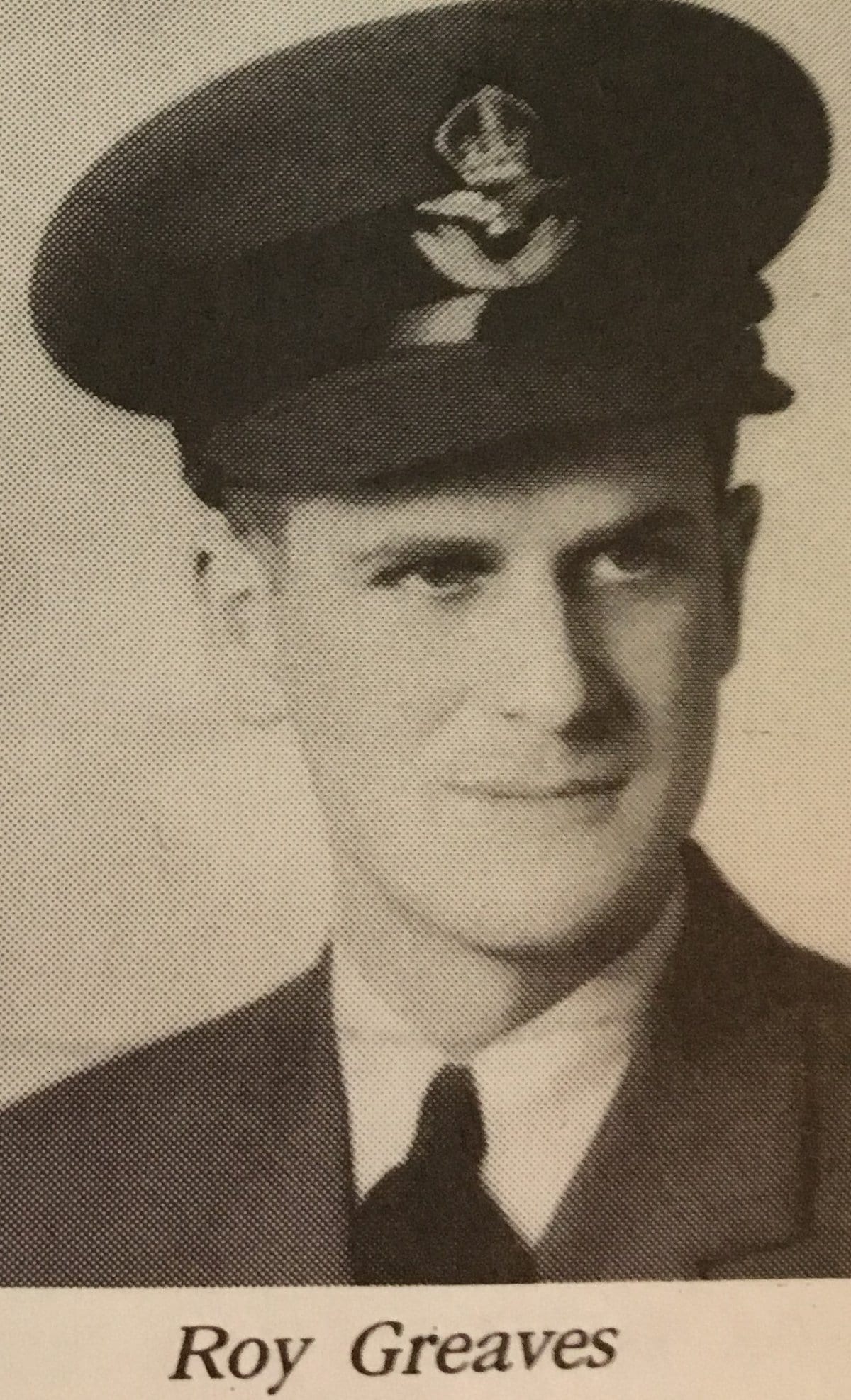

This was the case with Pilot Officer Roy Greaves, whose parents did not receive proof of their son’s death until two years after the war ended.

Roy was born on April 9, 1920, the youngest son of William and Mable Greaves, founders of Greaves Jams.

He began working for the Imperial bank in 1936, at both the Niagara-on-the-Lake and Niagara Falls branches.

In the spring of 1941, Greaves went to war. He enlisted in the RCAF in Hamilton on May 31 and was immediately sent to the Manning Depot in Toronto.

From there he was posted to the RCAF Station at Gander, Nfld., to be employed as an accounting clerk. Eight months later, he was at Scoudouc, N.B., again as a clerk.

At some point he decided that he wanted to take a more active role in the war.

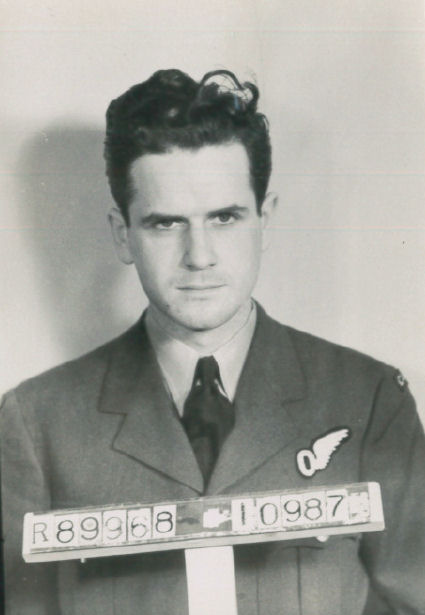

On July 19, 1942, he began training in Victoriaville, Que. He had declared that he wished to train as a pilot but the selection process for aircrew determined that he was more suitable to be trained as a navigator.

During training, he impressed the senior officers and was recommended for promotion to an officer’s rank. After further training he was commissioned.

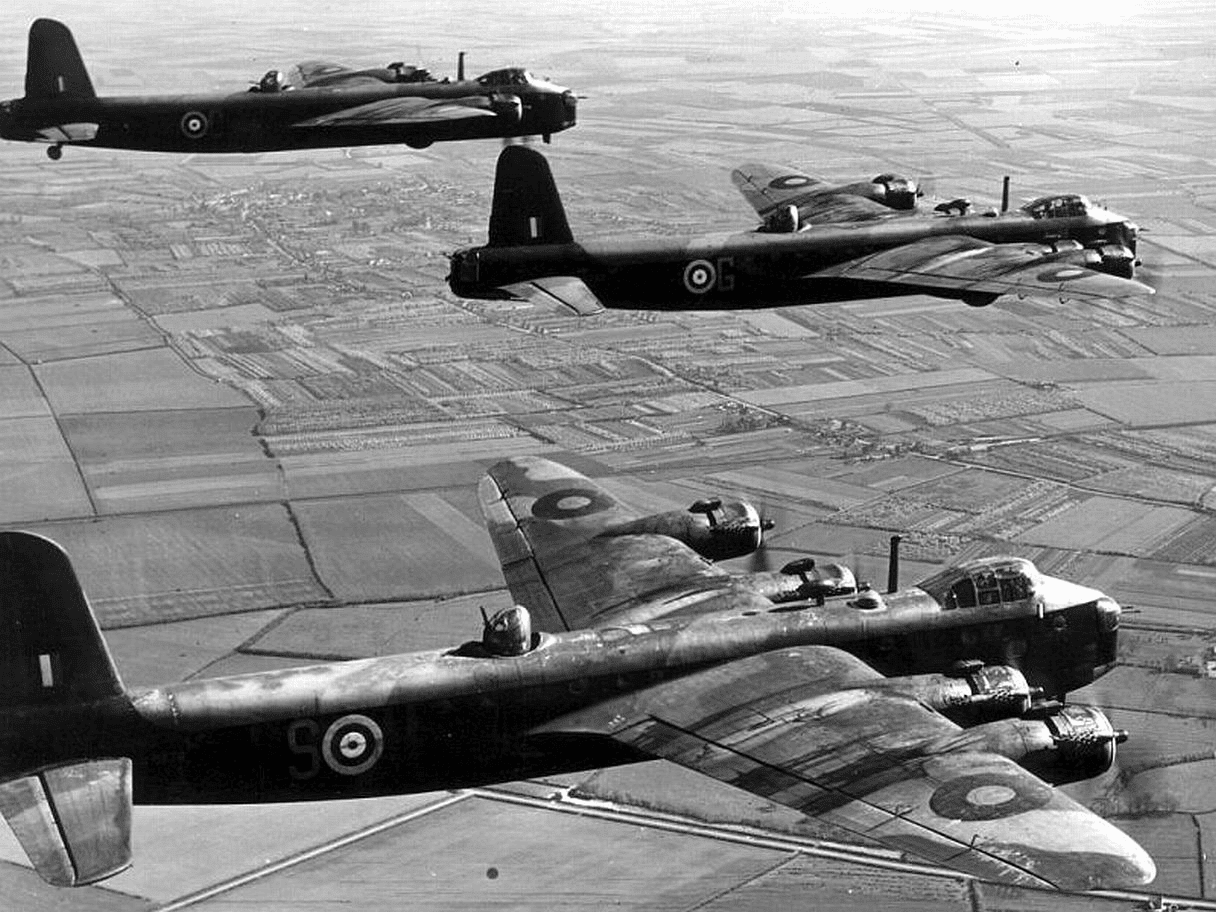

Pilot Officer Greaves was sent to England and reported to Royal Air Force 90 Squadron in Cambridgeshire.

He flew as a navigator in Stirling bomber BK 65. According to his commanding officer, “He took part in many raids and his navigation was confidently relied upon by his crew.”

His last raid was on Oct. 8-9, 1943, a bombing mission over Germany. His plane was shot down, crashing into a peat bog at Rhade, Germany.

When the plane failed to return to base, it was presumed to have been shot down. The commander of the squadron wrote to Greaves’ parents on Oct. 9 and while trying not to give them false hope, did just that.

He said that it was possible that the crew survived after a forced landing or by parachute descent.

It would be several months before the Red Cross reported that none of the crew of the missing plane were PoWs and that the Germans had found six bodies in the wreckage of Stirling number BK 65, but were able to identify only one of the crew members.

The Stirling had a crew of seven, so it seemed likely that one man had survived and had avoided capture. However, having heard nothing to the contrary for 11 months, the RCAF officially declared on Sept. 5, 1944, that Greaves had indeed been killed on Oct. 9, 1943.

Still there was hope, no matter how faint. There would be no closure until two years after the war ended.

On April 10, 1947, the Greaves family received a letter explaining that the Missing Research and Enquiry Service located the wreckage of their son’s plane and found the remains of one body in the wreckage. This was the missing seventh crew member.

Roy Greaves would not be coming home.