Niagara-on-the-Lake was a pulpit for the abolition of slavery in Canada, where signifiant events took place, such as the escape of runaway slave Solomon Moseby.

Moseby’s case had an underlying question: can property steal property?

In 1793, Sir John Graves Simcoe succeeded in pushing a law through parliament to abolish slavery in Upper Canada. There were many heated debates over how and when this should be done.

Would the law simply state that from that day forward there would be no slaves?

With many parliamentarians being slave owners themselves, the government knew such a broad stroke would never pass. How, they thought, could you tell a person he will no longer own valuable property?

That is, unjustly, how slaves were considered — as property, stock or inventory.

In one particular case, a slave owner became so concerned he would lose some of his ‘assets’ with the looming anti-slavery law that he forcibly sent one of his slaves, Chloe Cooley, across the Niagara River to a new ‘owner’.

She did not go willingly; pleading, screaming, kicking, biting and praying to stay in Upper Canada where she could feel the fresh breath of freedom blowing her way.

Simcoe, after hearing the horrible fate of this young girl, made great concessions with his executive council in Newark (NOTL) to have slavery gradually abolished in Upper Canada.

By July 9, 1793, it became law that the sale and import of slaves would no longer be permitted. Owners could keep the slaves they had, but the children of the slaves born after July 9, 1793 would be given their freedom when they turned 25. The following generation would be born free.

But what of the slaves who escaped from the plantations in the United States? Would they be free upon their arrival in Upper or Lower Canada? The answer was yes, unless the slave was accused of a crime.

This created a loophole, one which slave owners had been looking for; a plantation owner could very easily get a judge in the United States to issue a warrant that a runaway slave was a criminal and should be returned to their owner to stand trial for their crime in the US.

Canada now had a difficult decision to face — should slaves be returned to the United States, knowing they might not receive a fair trial for a purported crime?

This brings us to the case of Solomon Moseby.

Moseby was a slave who ‘belonged’ to David Castleman, a very wealthy and influential horse breeder in Kentucky. One day Castleman gave Moseby a horse, a travel pass and instructions to take a message to another plantation owner. It was then, in 1837, that Moseby saw his chance for freedom and headed to Upper Canada instead.

He was horseless be the time he reached his destination several months later, but he was free.

Castleman eventually found out Moseby was living in Niagara-on-the-Lake (NOTL) and showed up with a warrant to have Moseby extradited for the crime of stealing a horse.

The sheriff of NOTL, Alexander McLeod, had Moseby imprisoned and a case was prepared against him.

The residents of NOTL, both black and white, were horrified that a man might be sent back into slavery for stealing a horse.

Castleman claimed the horse in question was worth $150 and that he’d spent even more to travel to Canada to have Moseby extradited.

Residents of the town raised more than $1,000 to compensate Castleman but he refused the money.

Alexander Stewart, a lawyer from NOTL who was representing Moseby, contended that it was not the theft of the horse that Castleman cared about, but rather the return of his runaway slave — a ‘property’ more valuable than the horse.

The matter was sent to Sir Francis Bond Head, lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, who struggled with the decision — a decision that would affect Canada greatly.

Did he allow the government of the United States to order Canada to return a slave on the warrant of a judge who is also a slave owner? Should he accept all refugees regardless of their possible crimes committed in another country? Or should he send back any refugee whose crime and punishment would be considerably more than it would in Canada?

A resident of NOTL named Hugh Eccles sent Bond Head a petition signed by 117 white citizens, which declared that “neither morally nor legally can a slave be guilty of the offense charged against him; not being a free agent.”

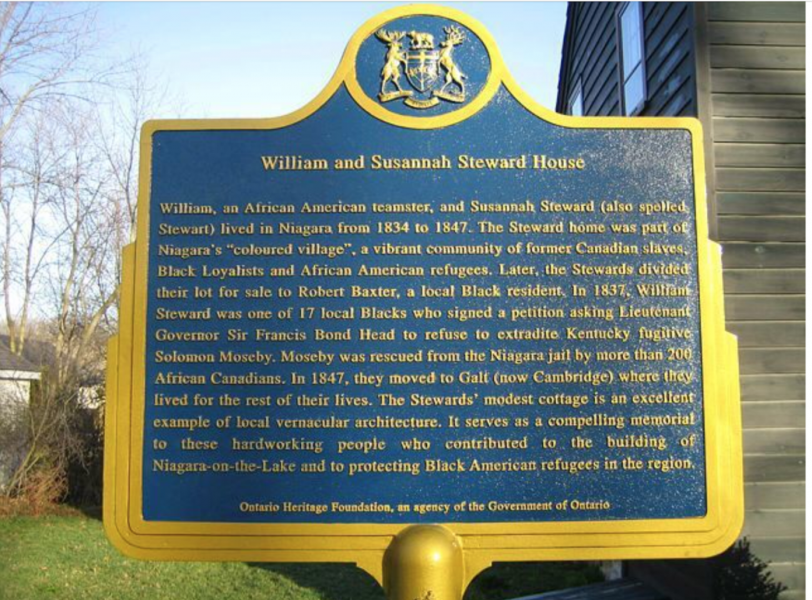

Seventeen black residents submitted their petition against the return of Moseby to his master, stating “exacted his sweat with stripes that mercy with a bleeding heart weeps when she see inflicted on a beast”.

Bond Head ignored these petitions and in September of 1837 declared that “this land of liberty cannot be made an Asylum for the guilty of any colour,” and ordered Moseby to be extradited back to the United States.

Local residents, both black and white held protests and blockaded the road. These demonstrations are described as having been peaceful, with religious songs being sung and sermons being preached.

Sheriff McLeod, hoping to tire the crowd, kept postponing the date of extradition, but this did not deter the people from standing up for Moseby’s rights. White town’s people provided food and lodging, preachers came and gave sermons while more black supporters from surrounding communities came to join the protest.

A date was eventually set, but McLeod faced another setback when a man named Hugh Richardson, who owned the ferries that crossed the lower Niagara River, said no vessel of his would be employed to return a man to slavery.

Eventually another ferry operator was located, and a new date was announced, but it seems Moseby’s extradition was destined to be fraught with problems.

The day Moseby was taken from King Street courthouse jail in handcuffs and loaded into a carriage, the women in the crowd blocked a bridge the carriage needed to cross.

A local preacher named Herbert Holmes led the protests, standing in front of the horses while a man named Jacob Green pushed a fence post through the spokes of the carriage wheels.

The details get murky here, as eyewitness accounts vary from person to person, though the final result of the protest saw Holmes and Green killed and many of the women slashed and bloodied by the soldier’s bayonets. Though, in the confusion, Moseby was able to slip his handcuffs off and escape.

Newspapers at the time had differening views on what Bond Head’s decision should have been.

The St. Catharine’s Journal was on the side of the law; Canada was not a place for fugitive criminals.

The Niagara Reporter stated that a refugee slave should only be returned if accused of murder, arson or the rape of a white woman.

The Christian Guardian of Toronto wrote that only in Upper Canada did a black man have any legal status, and that in Kentucky, a black man was regarded as property, therefore if he committed a crime he would be punished by his owner just like a horse would be punished. In other words, the returned slave would never see the inside of a courtroom, so to have Moseby returned to Kentucky as a “horse thief” was a sham; property can’t steal property.

Several months later another case against a runaway slave, Jesse Happy, accused of stealing a horse was presented to Bond Head for a decision. On the advice of Bond Head’s executive council, he turned the matter over to the colonial secretary, Lord Glenelg.

Unlike Bond Head, Glenelg preferred flexibility and decided each case of a runaway slave being accused of a crime would be judged on an individual basis. His suggestion was to consider what crime was committed when a slave was trying to escape to freedom.

Glenelg’s policy guided all future claims to extradite runaway slaves. Owners from the southern plantations kept petitioning the Canadian courts without success until the American Civil War (1861-65) put a stop to all the petitions.

As to the opening question, today, thankfully, the answer is an overwhelming “no.”

____________________________________

To learn more about the topic of this story you can visit the Niagara Historical Society & Museum website at, www.niagarahistorical.museum, or visit the museum for yourself.

The Niagara Historical Museum is located at 43 Castlereagh Street, Niagara-on-the-Lake in Memorial Hall.

Visit, or give them a call at 905-468-3912.

Denise’s profile can be found here, niagaranow.com/profile.phtml/13