In my first article for Niagara Now, I spoke about an amazing woman, Janet Carnochan, who insisted that Niagara-on-the-Lake needed to preserve the history of the town.

As well, we all know about the famous walk Laura Secord took.

But there are several other women whose stories should be told. Here are four of them.

***

Eliza Taylor, nee Bell, was a poor Irish girl born in the town of Newry, near Belfast in Northern Ireland in 1785. Oh the horror her parents must have felt when in November 1800, at the age of 15, Eliza eloped with a British officer, Thomas Taylor.

The two lived for several years in the safety of Ireland, until the Napoleonic Wars overtook the continent of Europe from 1803 to 1815. Maybe to the relief of Eliza’s parents, her husband was shipped out to the wilderness of Upper Canada and not to the European continent.

At this time in history, women were permitted to accompany their husbands into war. Eliza counted herself “lucky” to be able to accompany her husband to Newark (NOTL) and Fort George.

Taylor was assigned as the Fort Major, which afforded Eliza the luxury as an officer’s wife to move the family into a home in the town and not have to live in the fort.

An American invasion of Newark on May 27, 1813, during the War of 1812, saw her luck run out. The bombardment from Fort Niagara on the American side of Niagara River saw a cannon ball strike Eliza’s home. With four children to keep safe, she knew it was time to leave.

It must be understood that the wife of a military officer is on her own. When trouble strikes, the officer’s first duty is to his regiment, not his family.

While Taylor was on the march with his regiment out of the fort and heading to Burlington Heights (near Burlington Ontario today), Eliza bundled up the children, took what she could carry and headed to the “wilderness”, the home of the Claus family.

This wilderness property is located at 407 King Street, across from the legion in Niagara-on- the-Lake.

As Mr. Claus was the Superintendant of Indian Affairs, Eliza felt she and her children would be safe there. Imagine her dismay when she arrived at the home to find the Claus family had fled.

American soldiers were already looting the home and soon torched the house and barn. With no buildings around to seek shelter, she ended up moving her family into a fruit cellar on the property which many described as nothing more than a pit.

Eliza stayed there for several months, not knowing where her husband was, or if he was still alive.

She eventually managed to find passage by boat for her family to Fort Henry in Kingston, Upper Canada. There she received word her husband was alive but had been wounded in the Battle of Stoney Creek, June 6, 1813.

Being an officer, her husband had been transported to the town of York (Toronto) to convalesce, so Eliza, with all four children, made her way to York to assist with her husband’s recovery.

After the war, the family moved to a small town called Hamilton.

Mr. Taylor is recorded as being the town’s First Chairman (Mayor).

Eliza Taylor was in NOTL visiting her sister when she passed away on June 6, 1833 at the age of 46. She is buried in at St. Mark’s Anglican Church.

***

Mary Madden Henry was another Irish girl who married a British Officer and ended up in NOTL. She however was in town long before the war of 1812 broke out. In fact, her husband Dominic Henry retired from the British army in 1804 and was appointed the lighthouse keeper.

The lighthouse, located at the point where the Niagara River flows into Lake Ontario, was the first one to be built on the Great Lakes.

Unfortunately it was torn down after the war of 1812 to make way for Fort Mississauga, which was built on the foundations of the light house.

The fort can still be viewed at the end of the first hole in the Niagara-on- the-Lake Golf Course located at 143 Front St.

On May 27 of 1813, the American forces invaded, landing on the shores of Lake Ontario just north of the town. There is a cairn, at the north end of the Niagara-on- the-Lake Golf Course, marking the landing site and telling the story of the invasion.

Nowhere in the town was safe as cannon balls were flying from American ships on the lake and from Fort Niagara. The lighthouse though was spared the bombardment as the Americans knew that it would be useful to them once the war was over.

All around the lighthouse bullets whipped through the air, cannon balls exploded and smoke fumed all around amidst the cries of wounded men coming from the battle field.

Henry, knowing her husband would have been killed or captured, ordered him to stay in the lighthouse with their children while she went out on to the battle field to help where she could.

She took water or biscuits to any and all wounded soldiers and did her best with attending to the injured. She would sit with a soldier as he lay dying. Some soldiers wrote she was like an angel walking through the “mist” to help them.

After the battle, Henry continued helping the town’s folks who had been injured in the invasion. It was because of her courage on the battle field, even helping wounded American soldiers, that she and her family were left alone at the light house.

Then, on Dec. 13, 1813, the Americans retreated from the town, but not before they torched the homes. Many people, desperate to save their few belongings headed out to the lighthouse.

Henry and her husband packed the lighthouse tight with whatever belongings people came with. Their small home was also packed with people trying to survive the cold winter months.

After the war, Mary Madden Henry was compensated for her war losses and recognised for her heroism.

She died in 1823 and is also buried at St. Mark’s.

***

Another formidable woman, Matilda Boulton, was born In 1857. She lived to be 94-years-old, and in all those years she made sure people knew she meant business.

Boulton lived above a shop on Queen Street but she also owned property that ran down to Niagara River. There is a delightful tale of her suing the town of Niagara-on- the-Lake for stealing her property.

The town had given permission to dredge the river to remove the excess sediment so that the dock company could continue to operate their business, however Boulton claimed her property line extended 10 feet into the river. She had not given permission to the town to dredge her shoreline, therefore she believed they had stolen her property.

Boulton won her case.

Throughout her life she seemed to be in one battle after another with the town, evidenced by some letters Boulton sent to the town in 1903 about a property she owned.

She had rented the property to a widow, Mrs. A Clement and her two children and apparently the widow was having great difficulty with paying the rent.

However, Boulton did not keep up the payment of taxes on this property which forced the town to go after the rent money directly to pay the tax debt. Letters from Boulton regarding the show of force by the two town’s tax collectors (Reid and Burns), indicated how much she despised the two men. She wrote they should go after other properties that were in arrears and even suggesting they be removed from their positions.

In another letter from 1903, she references that Mayor James Aikens suggested she was not a lady nor a client of the town’s. She wrote back, “thank God I am not a lady, but a woman who has tried to do good and carry on with her businesses.”

Sounds like Boulton would fit right in with today’s women and the marches being held across the continent.

Boulton, who dressed in harsh black outfits, became outraged over the different fashion styles that came through the decades. She was absolutely appalled when skirts became shorter, exposing ladies' ankles, and even more furious when women started wearing shorts. She was known to have struck many a young lady across their exposed ankles and then legs for such a blatant disregard of etiquette.

Then there was another new invention which she found intolerable — the roller skate. She was known to throw water onto to roller skaters who dare pass her home.

Boulton passed away May 7, 1951.

Some of the town’s people might have been relieved at her passing, or maybe not, as quite a colourful character had left their lives.

***

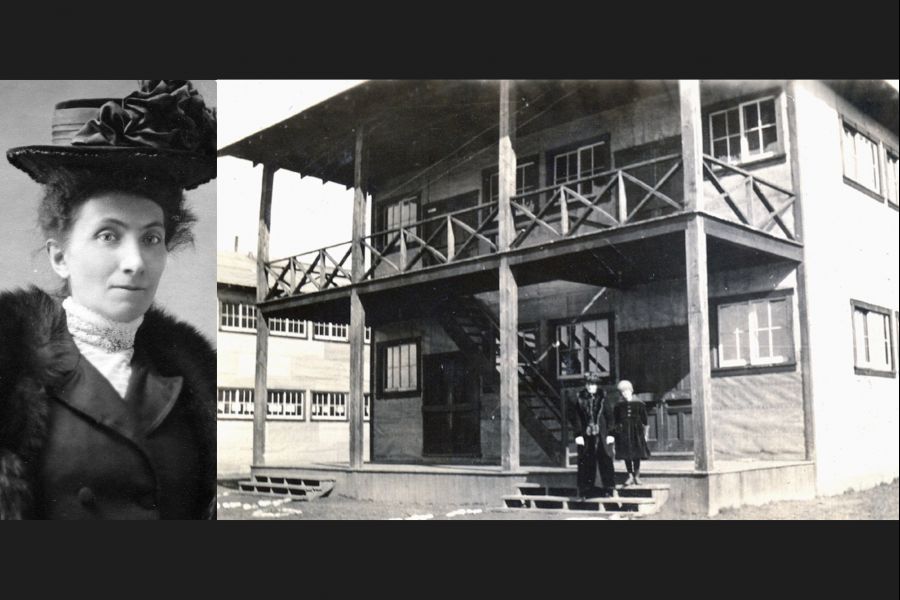

Finally I shall tell you the story of Elizabeth Ascher — kind of heart, but with a back bone made of steel.

It was during World War One that Ascher saw the plight of the Polish soldiers that were training at a Niagara camp. The soldiers did not have proper kits for winter training with only two wool blankets having been issued to keep them warm as they slept in canvas tents out on the commons.

Ascher was determined that these young Polish men should not be forced into such appalling conditions, especially knowing that many would die in the trenches overseas in Europe, so she set herself and the town’s people to task to get every single one of those young men in proper beds. Schools, town offices, churches, warehouses, the cannery and private homes were made into temporary barracks.

If Ascher found out you had spare room, even if it was your dining room, she badgered you into taking in a couple of the Polish soldiers.

Ascher organized letter writing sessions for the young Polish men. Many were not literate so she would pair them with someone who could write for them. She even had the library bring in Polish books and arranged music concerts with a Polish repertoire.

In July 1918, Ascher had world-renowned pianist Jan Paderewski visit the camp. Paderewski later became Premier of a free Poland.

Ascher, in the summer months, set up dances in the pavilion that once was located in Simcoe Park. The young men would buy a strip of tickets and then use a ticket to ask a young lady for a dance. There were plenty of matrons on the side lines to make sure that nothing inappropriate was going on — dancing too close was definitely frowned upon.

It was during the flu pandemic that swept through the world in 1918 and 1919 when 41 young Polish soldiers died here in NOTL. Some had family that could claim the bodies of their sons, but 24 were not as lucky. Ascher arranged for them to be buried together in St. Vincent de Paul graveyard.

When World War One was over, Canada ceded the cemetery to Poland so that these brave young men could be officially buried in Poland, the country they were so willing to defend.

Even when the war was over, Ascher continued her support of Poland. She pushed through a campaign to raise money, as well as to send clothing and medical supplies over to Poland as it struggled to recover from the war.

Ascher received numerous awards for her dedication to helping the Polish soldiers in Niagara.

In October of 1922, she received one of the highest honours from the Polish government:

Commander Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta (the equivalent of a Knighthood).

In November of 1923, she received the Hallar Medal; in May of 1926 the Order of Miecze Hallerowskie; and in May 1934 she received the Cross of Merit.

Ascher was the first woman and non-Polish citizen to receive these honours.

She was also awarded the rank of Honorary Colonel of the Polish Army and was inducted as a life member in the Polish Army Veterans Association.

Ascher died in April of 1941 at the age of 62.

The Polish community continues to remember and honour her name.

Each year, on the first Sunday in June, Polish legions from Buffalo send representatives to NOTL to honour the young men who are buried in St. Vincent de Paul’s Polish grave site.

The delegates then cross Byron Street and enter St. Mark’s graveyard where they lay wreaths at Ascher’s grave.

Note of interest: Elizabeth Ascher’s last name is spelled incorrectly on her grave marker. It is spelled Asher.

The Niagara Historical Society and Museum has a wonderful exhibition commemorating the 100th anniversary of Camp Kosciuszko, the Polish Army that trained at Niagara Camp.

From November of 1917 until the last camp closed in March 1919, over 22,000 Polish men trained in NOTL. Of those, 21,000 of the men were been shipped to France to serve in the Polish “Blue” Army. The World War One exhibition runs until November 2018.

____________________________________

To learn more about the topic of this story you can visit the Niagara Historical Society & Museum website at, niagarahistorical.museum.ca, or visit the museum for yourself.

The Niagara Historical Museum is located at 43 Castlereagh Street, Niagara-on-the-Lake in Memorial Hall.

Visit, or give them a call at 905-468-3912.

Denise's full profile can be found here, niagaranow.com/profile.phtml/13.